Excitement continues to build within the beef industry, spurred by higher prices for every class of cattle. After almost a decade of lower prices and more recently drought plaguing the central and western U.S., positive news is welcome. Escalating prices spawn recollection of market conditions in 2014-15, when 5-weight steers topped $300 per hundredweight (cwt) and fed cattle marked a record-high $172 cwt. The cow-calf sector experienced record-high profits during this two-year span. Fed cattle have surpassed the previous record by over $10 cwt and feeders are closing in on a new record-high price. The looming question is: Will record-high profitability again accompany record-high prices? The answer to this question will be influenced by factors discussed below.

Cost of capital

Interest rates have risen sharply since 2014. The Federal Funds Effective Rate (FRED) for most of 2014 was 0.09%; the September 2023 rate was 5.33%, a fifty-ninefold increase. FRED influences operating loan rates but is immune to regional volatility and borrower-specific interest rates. The cost of capital (and hence unit cost of production) has increased significantly over the past decade.

Health of the economy

The consumer price index has risen 29.6% from 2014 to 2023; according to the Federal Reserve Bank in St. Louis, average salary in the U.S. has risen 13% during the same period. The cost of living is outpacing wages, and consumer budgets are tightening. The increases in pay for most Americans: this affects the industry in two ways. First, the average consumer is experiencing a tighter budget. Contrast the current scenario with 2014; low interest rates and minimal inflation encouraged consumer spending and expansion of the economy as beef prices were rising. Market dynamics will encourage expansion of the cow herd, retention of heifers, reduction of feeder cattle inventory and rising cattle prices, all while consumer purchasing power is decreasing.

Drought

Since 2020, the central and western U.S. has experienced significant drought, causing destocking and liquidation of cow herds. According to the Nov. 16, 2023, U.S. Drought Monitor, almost 50% of the country remains in moderate drought. Widespread drought has driven cow inventories to the lowest number since 1962. Drought relief and pasture recovery will be primary drivers of cow herd rebuilding.

Beef cow inventory

Cow inventory is a function of heifer retention and cow slaughter. Feedlot inventory estimates published by the USDA in the latest quarter report suggest that over 40% of the cattle on feed are heifers. Historical evidence indicates herd expansion via heifer retention does not occur until heifer contribution to the fed cattle mix drops below 37%. As a result of drought-forced stocking rates reductions, the older and less productive cows have been culled, resulting in a relatively young cow herd. Culling young productive cows with greater reproductive efficiency will have a larger impact on feeder cattle inventory per cow removed from the herd. As soil moisture and pasture conditions improve, cow harvest and beef production from there will decline, encouraging higher beef prices.

Consumer demand

The ultimate driver of beef price is consumer demand. Despite higher prices (especially compared to competing animal proteins), beef demand remains strong. Year-over-year per-capita consumption is expected to drop 2%, but in the face of shrinking domestic supply, the small reduction is not expected to impact prices. Strength of the U.S. dollar is reducing beef exports and encouraging imports, both of which increase beef availability to U.S. consumers. Imports will predominately be lean beef for grinding and inclusion in further processed products. For this discussion, it is assumed imports will not significantly hinder domestic beef prices.

Cattle price vs. enterprise profitability

According to basic economic theory, steady demand combined with shrinking supply translates into higher prices and an optimistic future for beef. New record-high prices are the talk across the industry, but will cow-calf enterprise profitability follow a parallel track? Answering this question requires comparison of current prices to the record-high prices experienced in 2014 and 2015.

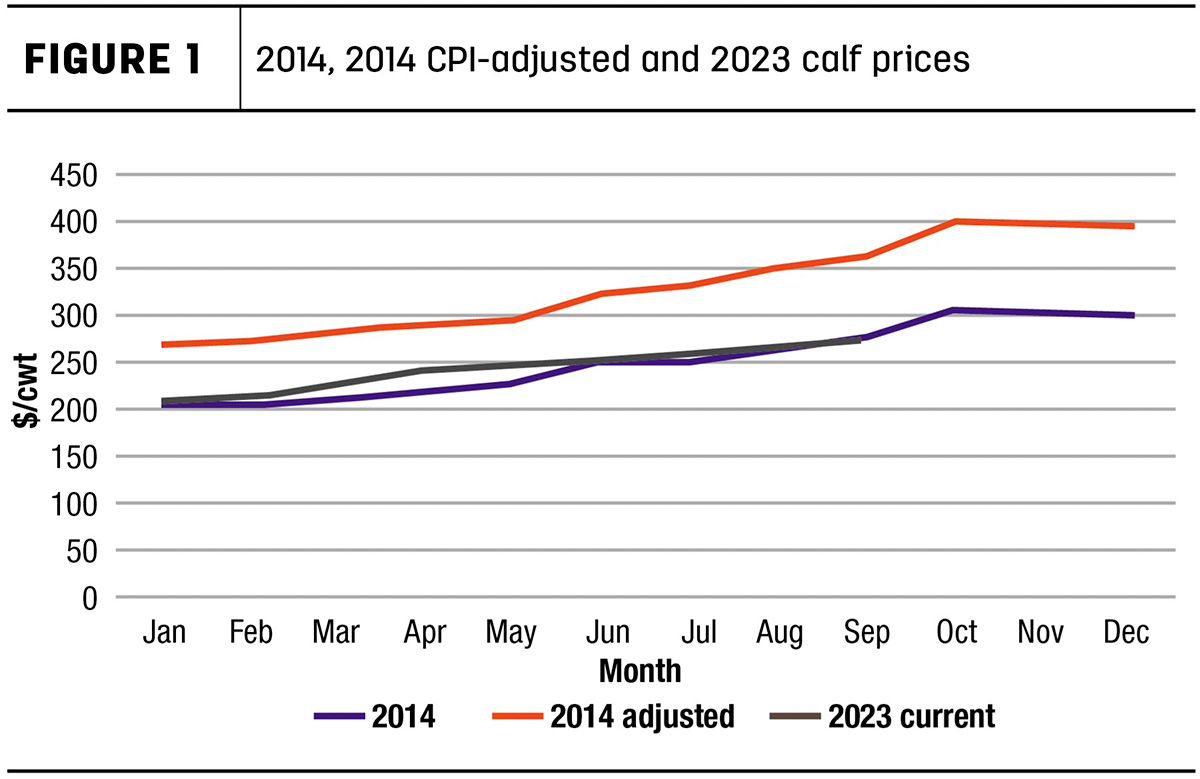

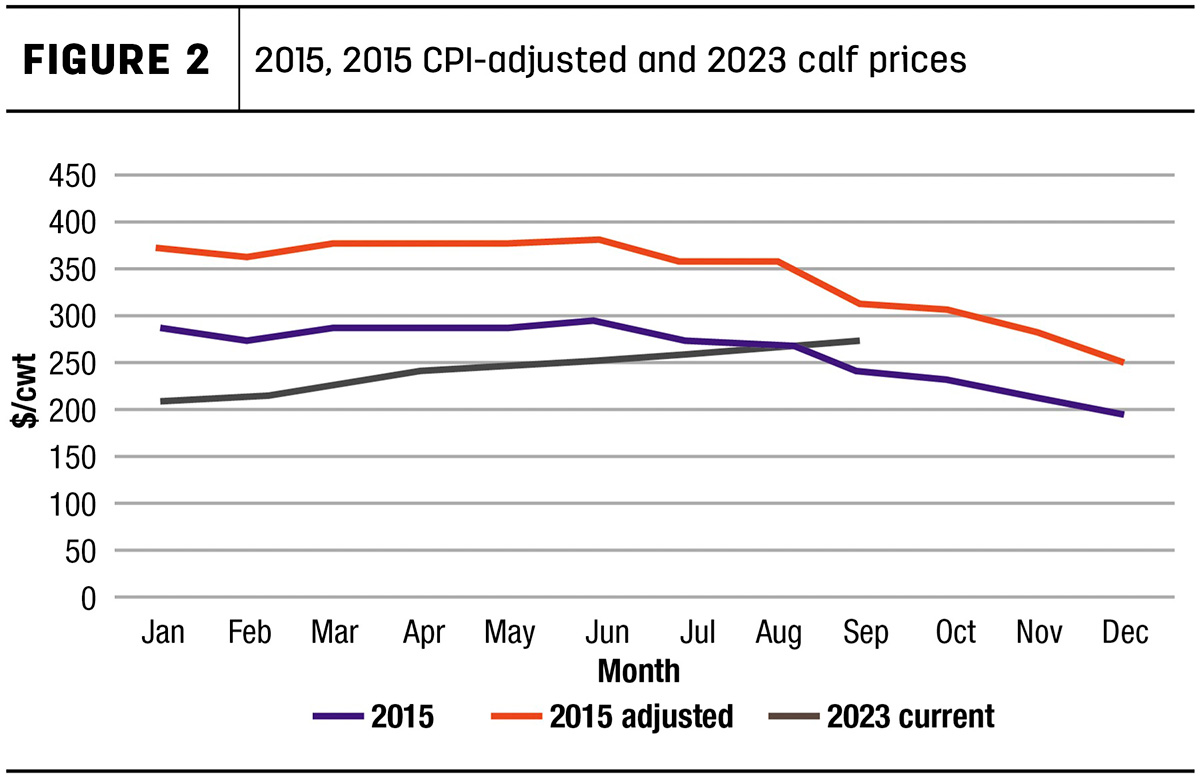

Comparison of current to previous prices requires adjustment for inflation. In Figures 1 and 2 for 2014 and 2015 respectively, a blue line represents USDA-NASS reported 500-pound calf prices for 2014, the orange line is the 2014 prices multiplied by an escalator of 29.6% (CPI, 2014 vs. 2023) to account for inflation, and the gray line represents 2023 year-to-date 500-pound calf prices from the same USDA-NASS database.

Note that calf prices rose through the first three quarters of 2014, plateaued from October 2014 through June of 2015, then began to decline. By 2016, calf prices had returned to pre-2014 levels. Calf prices in 2023 are on track and parallel with 2014-15. However, when adjusted for a decade of inflation (orange adjusted lines), it is obvious that appreciably higher record highs will be required to yield the same purchasing power of 2014-15. To have similar economic impact, the inflation-adjusted record-high calf prices this go-round will need to approach $400 cwt. Admittedly, in addition to inflation, there are other factors that dictate profitability (fixed costs, reproductive performance, weaning weight, unit cost of production, etc.). The point: Calf prices that simply surpass the 2014-15 record highs will likely not yield record cow-calf enterprise profitability.

Record-high calf prices experienced almost a decade ago were driven by consumer demand for beef. Similar to current conditions, the drought that ended in 2012 had reduced beef cow inventory, cow slaughter and concomitantly lean beef for grinding. Strong domestic demand for ground beef (approximately 50% of domestic beef consumption is ground beef) resulted in the disproportionate grinding of chucks and rounds from fed cattle, driving fed cattle prices to record highs. High fed cattle prices pulled feeder cattle prices higher.

As previously mentioned, the period of record-high calf prices was relatively short-lived; at most, producers captured record-high prices for two calf crops. Heifer retention began in 2013 prior to the rise in calf prices. Most of the heifers retained in 2013 calved in 2016 and contributed to the feeder cattle supply. In contrast for this cycle, heifer retention has yet to commence, suggesting calf prices should plateau higher rather than peak and decline as they did in 2015. If forage conditions improve and heifer retention begins in 2024, the earliest boost to domestic feeder cattle inventory would occur in 2026.

Profitability is defined as total income (price x units) minus total cost of production. Calf price is but one part of the profitability equation. Price discovery (the culmination of the marketing process) is readily apparent; determination of unit cost of production is more laborious. Independent of unit cost of production, the suitability of market price is difficult to assess.

Cow-calf producers have relatively little control over market price but are solely responsible for cow herd production and the associated costs. Low-cost producers who optimize production have been and will continue to be best positioned to benefit from record-high prices. For those exceptional managers, record-high calf prices will result in record annual profits.

Seb Killpack and Nathan Clackum contributed to this article, and they are King Ranch Institute for Ranch Management graduate students.

This article originally appeared in the King Ranch Institute for Ranch Management newsletter, Winter 2024.