A daughter of a dairy farmer once told me this story about her dad: “He doesn’t talk about things often. He bottles it up inside, and then it gets to a breaking point before they do something about it. Even physically. My dad never broke a bone in his life until he once fell asleep in the chair, stood up, got a spiral crack in his ankle. This happened at 11 p.m., so he went to the emergency room, got a boot on and was milking the next day at 4:30 a.m. He just put a garbage bag around it [laughs]. That's just how it goes on the farm.”

Myself and my team at the University of Alberta’s Augustana Campus heard a lot of stories like this over the past year as we initiated a series of studies to understand farmer mental health in the province.

For many, the life of a farmer sounds peaceful: living in the countryside, working outdoors, growing our food – but a scratch on that surface is going to show a much different reality. Farmers face a unique set of stressors including unpredictable weather, long work hours, geographical and social isolation, and limited access to healthcare. We’re now learning how these factors may significantly impact their mental well-being.

Our first insights into farmers' mental health in Canada came from studies conducted by researchers at the University of Guelph. In 2015-16, they found 35% of farmers met the criteria for depression, while 58% met the criteria for anxiety. A second study conducted during the pandemic showed mental health outcomes for farmers had worsened.

While this research shifted the spotlight to farmers’ well-being, it also raised a lot of questions, such as: Are there regional differences in mental health, and how do commodity groups differ? In Alberta, we found ourselves in a situation where there was no research on our farmers despite the province contributing over 25% of the country's total farm revenue in 2021.

To address this gap, myself and a team of undergraduate students (all of whom had a background in farming) conducted a province-wide survey in 2023 to assess the stressors faced by Alberta farmers and the prevalence of mental health issues such as depression and anxiety. We collected feedback from over 350 farmers across the province.

The stresses farmers experience

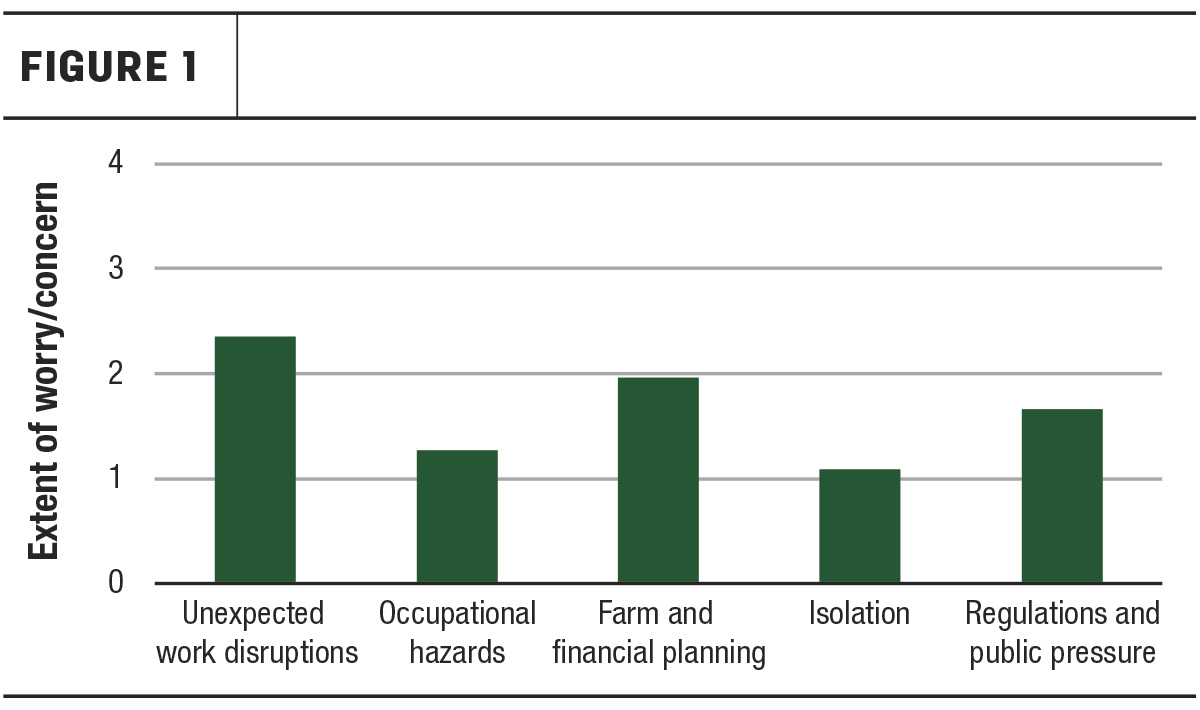

While we knew farmers experienced a range of stresses, we wanted to understand which stressors they found most concerning. So we asked farmers to rate how worrisome each stressor was. We then used computer software to cluster the common stresses together. This process created five stress categories, shown in Figure 1.

The top three stresses were unexpected work disruptions (e.g., machine breakdowns, time pressures, lack of manpower), farm and financial planning (e.g., getting farm loans, planning for retirement), and regulations and public pressure (e.g., government or industry regulations, changing policies). When reflecting on the remaining two stress categories, occupation hazards (e.g., operating machinery, handling chemicals, dust) and isolation (e.g., lack of close neighbors, distance to shopping centres), these are stresses that have always been present in farming but might be experienced differently across commodity groups. We noticed some interesting patterns: Beef cattle farmers, oilseed and grain farmers, and beekeepers had the highest ratings for unexpected work disruptions and the lowest levels of isolation. In contrast, dairy farmers had the highest ratings for isolation, and regulations and public pressure.

What’s most important here, and something we try to communicate to people unfamiliar with farming, is that these stresses often happen at the same time with a cumulative impact on a farmer’s mental health.

Mental health outcomes

One farmer mentioned, “I don’t get off the farm a lot, so because of the seclusion, I used to feel like I was the only person that was having a hard time.” Just like stress, we found symptoms of depression and anxiety were very common among farmers.

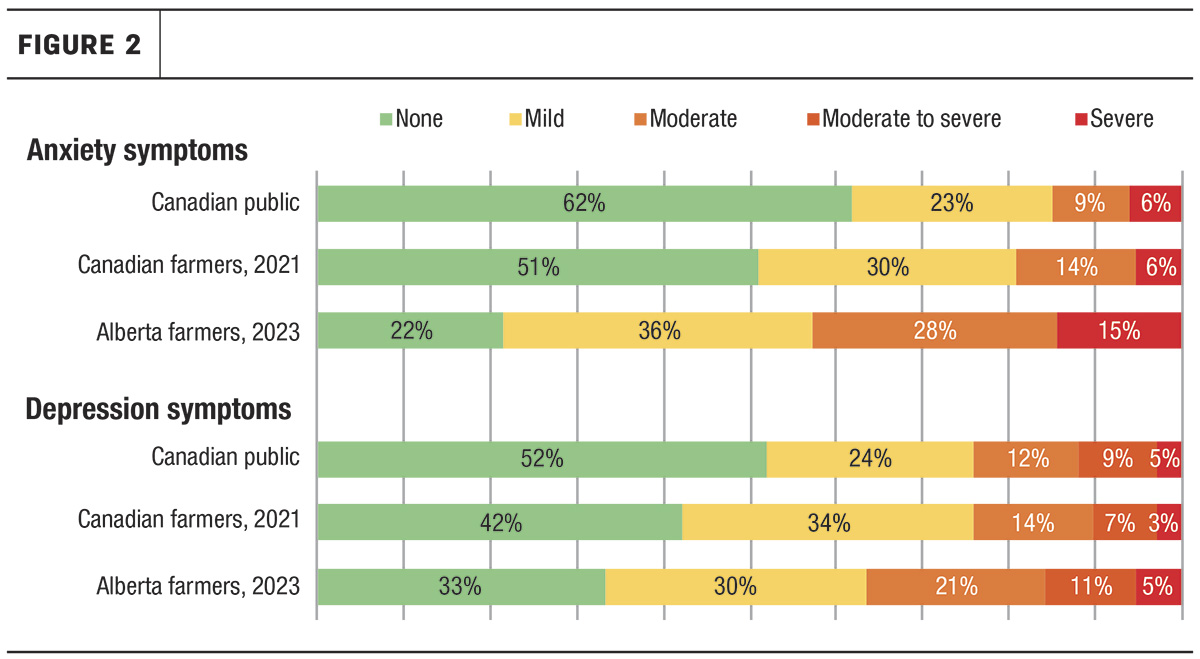

As shown in Figure 2, Alberta farmers experienced higher proportional rates of depressive symptoms and anxiety compared to the national average of Canadian farmers and the general population. While these scores are alarmingly high, they aren’t surprising. When the survey was conducted, the province didn’t have dedicated farmer-specific programs to address their mental health and there were serious droughts and wildfires.

Examining differences across commodity groups revealed dairy farmers had some of the highest rates of depression. While this finding is concerning, it can be beneficial in directing attention and resources to a group that might benefit from targeted support.

Depression can manifest in various ways, including increased irritability and anger, diminished interest in previously enjoyed activities, self-criticism, withdrawal and even physical symptoms such as stomachaches and headaches. Anxiety can present itself as excessive worrying or hypervigilance, procrastination and physical symptoms such as rapid heart rate and muscle tension in the chest, neck and jaw.

While all this sounds negative, Alberta farmers did score higher in resilience than the national average of Canadian farmers. Resilience is our ability to bounce back and continue working toward our goals after experiencing a struggle or setback.

How farmers cope

Whenever I share this data with agricultural groups, it opens the door to talk about the stresses, strains and struggles in farming, providing many with validation and the words to articulate what they've been feeling for years. From here, the discussion moved to coping.

Most farmers (39%) coped by taking time off or “unplugging.” Others (30%) worked on hobbies or socialized with family, friends and the animals. About 10% reported using recreational drugs or alcohol to “take the edge off.” Reflecting on the pattern of results, it is evident most farmers used escapism or distraction coping strategies, providing their brains with a short-term break but not effective long-term solutions. Only 6% used therapy.

While there are benefits to talking with a therapist, and efforts are underway to ensure farmers have easier access to therapists familiar with farming stresses, there are also practical steps farmers can take to give their brains some respite. Integrating easy tasks into the day, such as spraying down equipment, can provide a mental break while still feeling productive. Or choosing to walk instead of driving to check fences, which helps build in some exercise and walking outdoors, both of which are good for your brain.

References omitted but are available upon request by sending an email to the editor.

Dr. Rebecca Purc-Stephenson is the former lead researcher of AgKnow and a current board member for the Canadian Centre for Agricultural Wellbeing. She would like to acknowledge the support of the Agricultural Research and Extension Council of Alberta (ARECA) and the Alberta Ministry of Agriculture and Irrigation.