“Corn grain is a seed first, then a feed,” to paraphrase Pat Hoffman, professor at University of Wisconsin (UW). The starch in corn seed contains energy the seed uses to sprout and grow. The energy (starch) is protected for overwintering by a coating of zein (prolamin) protein. The zein is resistant to digestion by rumen bacteria, which must break through and degrade the protein coating to access the starch.

Zein protein has some value (though low in lysine) to the cow and nutritionist, but the primary nutrient of interest is starch. The presence of more zein slows the availability of starch.

Varieties differ in the amount of zein deposited around the starch. A greater degree of zein encasing starch can be seen as a more yellow/orange, translucent or vitreous (glassy) appearance. This is especially noticeable if the kernel is put above a light source or is split open.

If the kernel contents are more white, opaque or floury, less zein is present. Vitreous kernels are denser, so bushel weight is higher.

Selecting varieties with higher bushel weight (58-62 lbs) selects for more zein (prolamin) protein and lower ruminal and total starch digestion. These varieties need more extensive processing.

Conversely, lower bushel weight corn (54-58 lbs) typically has more ruminally available, floury starch (this excludes low bushel weight from poor ear fill or damaged kernels).

The amount of vitreous material can be quantified by dissection or with a zein prolamin assay. Work to better define the proportions has been ongoing for over 10 years.

UW researchers have recently developed the UW grain evaluation system to quantify digestibility of corn based on prolamin, moisture and particle size. Other measures of starch digestibility were discussed in the April 12, 2011, issue of Progressive Dairyman .

Energy in corn silage comes mainly from digestible starch in the kernel and digestible fiber, protein and other carbohydrates in the fodder. Corn is a grass plant, with a large grain component. Digestibility of the fiber contributes significantly to total energy supplied.

Brown mid-rib (BMR) corn has lower lignin and much higher fiber digestibility. Be aware that BM3 gene variety fiber digestibility is higher than BM1. BMR grain starch may be more slowly digestible, depending on the parent genetic line.

Wisconsin researchers (2009) reported ruminal and total starch digestibility in the following ranking by corn type: opaque > floury > sugary > waxy > normal (highest to lowest).

As the plant matures, sugars in the plant are converted to starch in the kernel. The final step prior to black layer maturity involves depositing zein (prolamin) protein around the starch granules for a coating of overwinter protection.

Less mature forage (earlier harvest/wetter) generally has more available starch. More floury varieties are less affected by maturity effects that reduce starch digestibility.

Dr. Mike Allen (2008) at Michigan State fed cows more vitreous or more floury corn and found that ruminal digestion of vitreous corn was 19 percentage units lower and total tract starch digestion decreased 9 percentage units.

Wisconsin researchers (2009) reported floury corn was 32 percent more digestible in vitro and 6 percent more digestible in cows compared to vitreous corn.

Plant breeder selection for higher starch digestion is occurring; however, it must be done in the context of overall plant agronomic, yield and other considerations. You can select varieties that have more digestible starch from those currently offered.

Ensiling effect on corn forage

We’ve known for several years that a significant contributor to the “fall slump” in production is due to new corn silage. Recent research has provided insight on why new silage doesn’t support as much production.

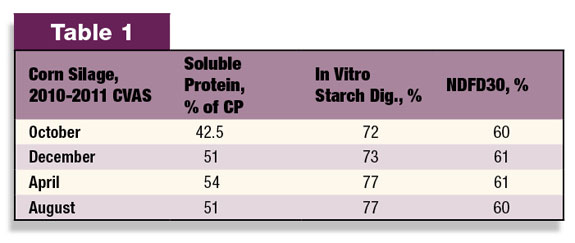

Also, spring/summer “acidosis” may be related to rapid ruminal fermentation from corn silage and high-moisture corn ensiled a long time. Cumberland Valley Analytical Services (CVAS) and other lab results show starch digestibility is lower for the first several months after ensiling and gradually increases over time.

Soluble protein (from zein breakdown) increases along with starch digestibility (IVSD7). IVSD7 varies within and between labs.

Interestingly, NDF digestibility is typically highest in the standing crop, drops initially as the most fermentable components are converted to acids or used by silage bacteria, then is relatively constant.

These averages are not based on sequential samples of the same forages sampled over multiple time points, however.

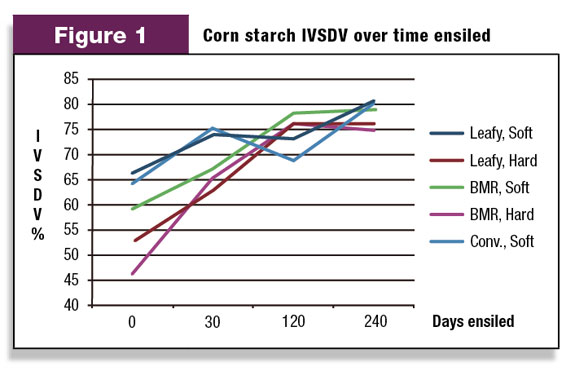

Dr. Limin Kung’s group at the University of Delaware (2010) ensiled two conventional and two BMR varieties at lower and higher dry matter and reported an increase in starch digestion over time.

BMR silage starch digestibility increased about twice as much as conventional.Changes over time like this have also been reported from Penn State University and Mycogen.

We evaluated samples with different forage and kernel hardness traits from the 2009-2010 silage crop at different ensiling times. We found IVSD7 increased as time ensiled increased.

We saw the same pattern with soluble protein. NDFD30 dropped initially, then was consistent.

Professor Hoffman and the UW research group published a trial in 2011 that identified the primary reason for changes in starch digestibility over time. Some consideration had been given to the possibility of acids or other compounds increasing availability of starch.

Their recent trial concluded bacterial action during ensiling was more important in breaking down the zein protein cross-linkages, therefore allowing rumen bacteria greater access to starch granules during digestion.

The extent of the zein protein – starch cross-linking appears to be related to the variety and maturity at harvest.

The degree of breakdown of the matrix, making starch more ruminally digestible, is related to the length of time ensiled. These differences are quite visually apparent when looking at electron micrographs.

High-moisture corn A is reflective of a more vitreous, later-maturity corn while B would be a more floury, earlier cut. Both show less zein protein encapsulating the starch granules after 240 days, but the change in the more floury corn is more dramatic.

CS feeding strategies

- Select corn varieties for high NDF and starch digestibility. Plant breeders continue to make advancements.

- Properly process corn kernels when harvesting. Fill fast, pack intensively, inoculate and cover to preserve all the value possible and drive silage fermentation.

- Have several months of carryover silage. If not, feed the least mature, wetter silage first and let the mature, drier silage ferment longer. Consider letting BMR ferment longer.

- Use lab analyses that provide information on starch and NDF digestibility. Use a ration model that allows balancing with those results to optimize production and components.

- If you feed silage immediately, provide more sources of fermentable carbohydrates and possibly bypass protein to compensate for less fermentable starch and lower microbial protein yield from the fresh silage.

- Control fermentable starch levels in rations as silage starch fermentability increases in spring/summer after months of ensiling. PD

Reprinted with permission from Elsevier

-

Dr. Tim Snyder

- Nutrition Manager

- Renaissance Nutrition, Inc.

- Email Dr. Tim Snyder