The number of U.S. farms restructuring debt by filing Chapter 12 bankruptcy in the past year was lower than a year earlier. However, filings were higher in regions most heavily dependent on dairy and row crops for income.

National analysis by American Farm Bureau Federation (AFBF) chief economist John Newton (Read: Chapter 12 bankruptcies lower across farm country, posted on AFBF’s Market Intel website) shows Chapter 12 filings totaled 468 for the fiscal year 2018, down about 8 percent from a year earlier. Newton’s summary looked at U.S. court caseload statistics for the fiscal year ending Sept. 30, 2018.

With projections for low farm income, record nominal agricultural debt, rising debt-to-asset ratios and interest rates, and continued headwinds for agricultural commodity prices, more bankruptcies had been anticipated, Newton said. Chapter 12 filings in fiscal year 2018 were down from 508 in fiscal year 2017, but approximately 25 percent higher than in 2014.

Regionally, Chapter 12 bankruptcy filings were higher than year-ago levels in several district courts, including District 2 (Connecticut, New York and Vermont); District 7 (Illinois, Indiana and Wisconsin); District 8 (Arkansas, Iowa, Minnesota, Missouri, Nebraska, North Dakota and South Dakota) and District 10 (Colorado, Kansas, New Mexico, Oklahoma, Utah and Wyoming). More than 50 percent (252 filings) of total U.S. Chapter 12 filings were in those districts, characterized by highly concentrated traditional row crop, livestock and dairy production.

A closer look at the Minneapolis Federal Reserve district

The nagging economic strain of low commodity prices on farmers – compounded by the impact of trade tariffs — is showing up in farm viability within the Federal Reserve Bank’s ninth district, according to Ronald Wirtz, regional outreach director, based in Minneapolis, Minnesota. (Read: Chapter 12 bankruptcies on the rise in the ninth district.)

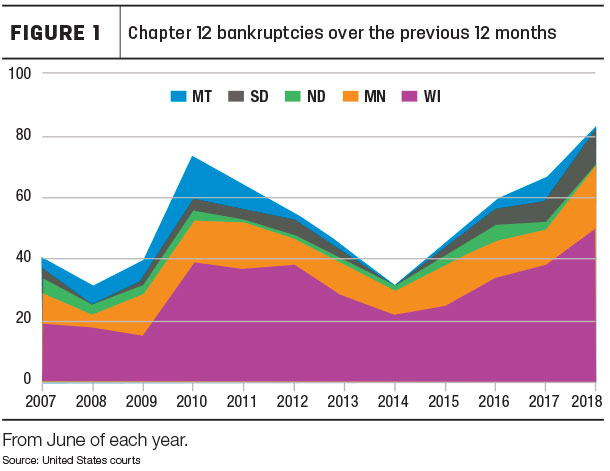

Over the 12 months ending in June 2018, 84 farm operations in the district – which covers all or portions of Minnesota, Montana, North Dakota, South Dakota and Wisconsin – had filed for Chapter 12 bankruptcy protection – more than twice the level seen in June 2014 (Figure 1). Chapter 12 bankruptcy filings within the district previously spiked during the recent “Great Recession,” reaching 70 in 2010. Following the rise and fall of commodity prices, farm bankruptcies bottomed out in 2014, but have moved higher since then. Current commodity price levels suggest the ongoing trajectory has not yet seen a peak, Wirtz warned.

Not all states within the Federal Reserve district are feeling the same effects, Wirtz said. With its economic foundation on dairy, Wisconsin, for example, is seeing about 60 percent of all bankruptcies among district states. Though the state is the country’s No. 2 milk producer, it still has many small farms, which tend to be more exposed to large price fluctuations.

Chapter 12 provides flexibility

Designed for family farmers with "regular annual income,” Chapter 12 bankruptcy allows financially distressed farmers to restructure financials and propose a repayment plan – usually over a three- to five-year period – to avoid a liquidation of assets or foreclosure, Newton explained.

Chapter 12 bankruptcy has been around for about three decades, created after the farm crisis of the 1980s, according to Wirtz. Chapter 12 provisions eliminate certain barriers that farmers would face if they sought protection from debtors under either Chapter 11 or Chapter 13 of the bankruptcy code. It also provides for payment flexibility based on harvest and marketing schedules, given the seasonal nature of farm output.

Chapter 12 bankruptcies are viewed as the best indicator of farm bankruptcy trends, Newton said.

Despite the small year-to-year decline in overall Chapter 12 filings, the fiscal year 2018 data highlights the tough financial conditions across portions of rural America, and the USDA does not forecast improvements in solvency and liquidity ratios, Newton said. The USDA projects the debt-to-asset ratio to climb in 2018 to 13.4 percent – the highest level since 2009 and the sixth consecutive year of climbing debt-to-asset ratios. In addition, the debt-service ratio is projected to the highest level in 30 years. Poorer performing farm financial indicators suggest some farms may soon be unable to service debt with existing assets.

Bankruptcies are but one measure of the financial difficulty in agriculture. Many are leaving the business altogether, Wirtz noted. The number of licensed dairies in Wisconsin, for example, has fallen by about 1,475 (15 percent) from Jan. 1, 2016, to Nov. 1, 2018. ![]()

-

Dave Natzke

- Editor

- Progressive Dairyman

- Email Dave Natzke