Recently, a client of mine had been losing what little premium co-ops are still offering for milk quality – to the tune of around $50,000. With this past year’s milk price, this extra cash for achieving quality was a huge loss for my client.

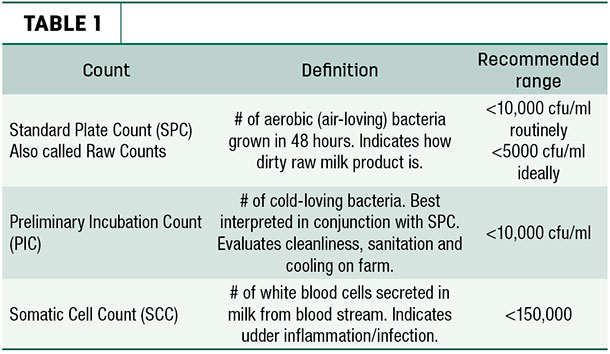

What was the issue? Elevated standard plate counts (spc), elevated preliminary incubation counts (pic) and increasing somatic cell counts (SCC). Table 1 includes definitions of these counts.

Now, back to the case. From about August 2016 through January 2017, the SPC on this farm was bouncing around from 4,000 colony-forming units (cfu) per milliliter up to as high as 24,000 cfu per milliliter. In addition to the fluctuating SPC, the PI count was fluctuating between 7,000 cfu per milliliter and 1.1 million cfu per milliliter.

Lastly, the average SCC for this herd in 2016 was around 100,000. Within a few months, the SCC was climbing as high as 190,000. Although this SCC is not terrible, their SCC is trending upward, indicating an increase in inflammation or infection of the udder. So where do you start with this investigation?

As cleanliness is one of the major factors affecting these counts, it makes sense to start with the wash system. The farm had a milking systems company coming on a regular basis. However, past experience with this company had been disappointing.

They were also on a regularly scheduled visit with a chemical consultant, as they were having issues with large amounts of iron buildup in the water. Fortunately, this consultant also had an interest in milking systems.

With the client expressing concerns over these counts and questioning if iron buildup was contributing, the chemical consultant started looking around. Every visit, she would find issues in the milking system that needed to be corrected. Some were small items, such as a kink in the hose from the detergent jar to the line.

Other findings, such as the units farthest from the milkhouse not getting any water during the wash cycle, were much more critical.

So how does the vet play into this? As a clinic, we also offer complete milking systems analysis. However, since they had already started working with the chemical company, we worked as a team in a comprehensive approach. As a diagnostician, I ask lots of questions, starting at the beginning with the entire picture in mind.

First, is the entire wash system being run? Are the milkers shutting it off early because it’s noon and they are supposed to be milking again by then?

In a parlor that is maxed out and with an owner concerned about the number of cows per hour being milked, do the milkers feel rushed? In this case, the employees were shutting off the wash early so they could stay on schedule.

A simple re-training of why it is important to let the entire wash cycle run is crucial. Although this was a contributing factor, there were more critical issues in the parlor that needed to be corrected.

From the very basics, let’s move to the equipment and the wash cycle itself. Even with six drilled wells on the farm, this farm has an issue with water volume. Knowing this, I started asking if there was enough water and hot water to wash the system appropriately.

Also, if they are washing the bulk tank at the same time as the milking system, is there enough hot water to wash both appropriately? One of the biggest shortfalls in expansions is not making sure the equipment can handle the expansion. Do you need a bigger hot water heater? Do you need a larger vacuum pump?

Is the vacuum pump still operating as efficiently as it can? What about fresh air intakes? Are there enough? Is the reserve tank big enough? Is the wash vat big enough? Have you added on units and not changed the amount of water filling the wash vat?

The milking units and weigh jars should also be assessed when evaluating equipment. Did you know some gaskets are supposed to be changed every three months? Are you looking at them, saying, “They still look fine” and moving on? With hot water and chemicals, rubber starts to deteriorate.

Pitting can occur, and those pits are wonderful areas for bacteria to hide. Know how often your equipment needs to be replaced and change accordingly.

This also often occurs with inflations. Not only do some farms wait to change inflations, they may completely change brands of inflations and not adjust pulsation and vacuum levels accordingly. The short air hoses and milk line hoses are another area that often gets ignored. Are there dry cracks in those hoses? Are they loose and letting air in? Although we strive to keep milking parlors clean, they are not a sterile environment.

Any opportunity for bacteria to enter the milking system needs to be found and eliminated. This farm was doing a good job of changing hoses when needed, but their milking claw was an issue. Around the glass on the claw is a rubber gasket that was not fitting tightly.

Manure would get stuck in this gasket and would build up on the inside and outside of the claw. Along with an improperly working wash system, these gaskets were contributing to bacteria load.

I mentioned an improperly working wash system. When the wash cycle was running on this farm, we realized the units farthest away were not getting any water to them. Along with the poorly fitting claw gaskets, and a buildup of milkfat and protein that was never truly getting cleaned, the bacteria were living the dream.

A simple addition of restrictors into the units allowed all units to actually get washed. In addition to checking all units are getting washed, it is important to make sure there is a “slug” of washwater moving through the lines. This helps remove any buildup in the line. Prior to correction, this farm had hardly any slug hitting the receiver jar, resulting in line buildup – another wonderful environment for bacterial growth.

We’ve addressed the SPC and the PIC, but we haven’t yet addressed the SCC issue. During the milking process, the cow’s teat canal is wide open. If the units are dirty or the system is dirty, there is a good possibility that these wide-open teat canals are getting a five- to seven-minute bath of bacteria three times a day. No wonder SCC was increasing.

Clinical mastitis cases increased, milk production decreased, and there was money being left on the table day in and day out. However, to be thorough, we still need to evaluate the milking procedure and the cows.

Are we dealing with any contagious mastitis pathogens? Has there been any procedural drift in the milking prep routine? What is the condition of the teat ends? What kind of teat dips are we using to help with this? How clean are the stalls and the cows when they go to lie down after milking? Anything we can do to correct these contributing factors needs to be implemented.

The maintenance my client thought was being done on a routine basis was getting ignored. After some research, they found an independent milking systems technician who spent eight days getting their parlor fixed. Within one month, the PI count was down to 4,000 cfu per milliliter, the SPC was between 4,000 and 6,000 cfu per milliliter, and the SCC has ranged from 120,000 to 190,000.

Cows can’t rid their infections overnight. With a little more time, I know the SCC will be back where it belongs. They are now getting their quality premium again, which has certainly paid for hiring the right person to do the job correctly.

So now what? How do we prevent issues going forward? Routine monitoring. Keep a log of the issues and corrections in a notebook so you know when the last time the gaskets have been changed, the inflations were changed or the pulsators were rebuilt.

The milk companies tell you your counts. Watch them. Monitor them. Know when they are trending upward. Then, find a veterinarian, a trusted consultant or a systems technician who can evaluate the system on a quarterly basis and correctly fix the issues found. Your bottom line – and quite possibly your milk market – depend on it. ![]()

Carie Telgen

- Battenkill Veterinary

- Bovine P.C.

- Email Carrie Telgen