On Dec. 27, 1974, humanity suffered a loss, although most people outside of a certain small island wouldn’t have noticed. On that day, Ned Maddell, the last native speaker of Manx, passed away.

The Manx people were descendants of the Celts and inhabited the Isle of Man, a self-governing island of British Crown Dependency located between Ireland and the UK. The Manx culture, however, as well as its language, has been overcome by English influence. Today, most people on the island were not born there but instead are English settlers.

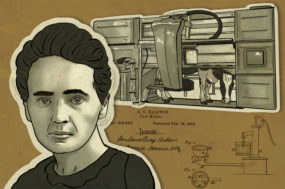

Manx began to disappear as a community language on the Isle of Man by the mid-1800s. However, as a child, Ned Farrell was sent to live with relatives in the remote village of Cregneash. Because his great-aunt could not speak English, Ned learned Manx. As a result, Ned helped act as a translator for the older inhabitants of the village who could not speak English. In the mid-20th century, the Manx Museum did not have the capability to make an audio recording of its last native speaker. However, the Irish Taoiseach (similar to prime minister) Éamon de Valera sent a person over to the Isle of Man with a crate of discs, ensuring that Ned and the language were preserved in a recording.

In the modern age, we’re used to hearing about extinct species of plants and animals and the biodiversity loss that represents. Intensive efforts are in place to protect the endangered flora and fauna that we still have. What’s less talked about, however, is the disappearance of languages. To date, 573 known languages have become extinct, many of them without any sort of recorded documentation. That, too, is a significant cultural loss to the world we live in.

It is not surprising that Ireland was behind the effort to record Ned Farrell. The country has been in a long fight to preserve its own native language, Irish (sometimes mistakenly called Gaelic). Due to persecution by the British, Irish was no longer the dominant language on the island by the middle of the 19th century. In order to assert complete control over the Irish people, the Crown sought to extinguish their culture, ultimately forbidding the speaking of their language.

Today, however, concerted efforts by the Irish government have been made to preserve and encourage the language, and a majority of elementary classes are taught in Irish. In certain parts of the country, Irish is still the first language. Additionally, in 2022 Irish was made a full working language of the European Union. Part of the drive to promote the Irish language is how it is seen as crucial to the culture of its people. Because a language influences the way a person thinks, it has been said that to truly know the Irish people, one must speak the Irish language. Even in English, many of their phrasal structures and linguistic idiosyncrasies trace back to Irish. For many people, learning Irish is a political act to reclaim an identity once taken from them.

It has been estimated that by the end of this century, 1,500 more languages may not be spoken anymore. In the U.S. and Canada, many Native American and First Nation languages have recently disappeared or will do so in another generation. While groups of people have risen and vanished throughout the course of history, the assimilation of current ethnicities has occurred at an accelerated rate in the modern age.

The Manx language traces back to the dominance of the Celtic people several millennia ago. Although they are associated with Western Europe – especially Ireland and Scotland – around 275 B.C. the Celts controlled most of Europe. While eventually defeated by the Romans, they remained a presence in Western Europe for much longer. There are six Celtic languages, four of which still have native speakers: Irish, Scottish Gaelic, Welsh and Breton. Like Manx, Cornish is also a Celtic language, but died out in 1777.

When Ned Farrell died, we lost a direct historical line that dated back to hundreds of years before Christ. It seemed like he himself knew what was at stake because he was very active in helping young people learn Manx. Between his efforts, and that of others on the Isle of Man, Manx has made a comeback. Currently, there are 2,200 speakers of the language, with a primary school taught in Manx, as well as pubs and cafes dedicated to promoting it. Because the language was spoken after officially being declared lost by UNESCO, Manx is only the second language – after Hebrew – to be successfully revitalized once it was gone. Through the language, the people on the Isle of Man were able to keep a part of their history and culture alive and participate in their ancient identity as well.