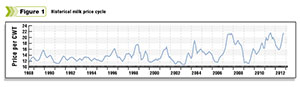

Whether it’s the fluctuating stock market, the roller coaster of real estate or changing interest rates, Americans have become used to the concept of price cycles. While U.S. dairy producers have experienced ups and downs in their milk prices too, what distinguished this market through the 1990s and early 2000s was the regularity of the U.S. dairy price cycle.

Several features of the U.S. dairy market combined to introduce this regular cyclicality. The reduction of intervention price floors by government agencies unleashed the inherent instability in the market – ensuring there would be price cycles. High import barriers and export subsidies effectively isolated the U.S. from the world beyond it, ensuring that the timing of these cycles would be determined locally.

The nature of the U.S. market itself then ensured the regularity of the ups and downs. Demand shocks were rare. And because the U.S. supply base was reasonably uniform, deploying similar production systems and facing a similar cost base, producers became either all profitable or all loss-making at a given point in time, producing too much milk or too little milk for local requirements as a result.

Altogether, these dynamics made for a surprisingly regular price cycle in the U.S. dairy market, with peaks 30 to 35 months apart. The cycle tracked closely to the breeding cycle of cows – three years between the decision to breed heifers and the offspring being able to come into production – and supporting the idea that lags in response to supply helped to shape the market cycle.

Enter price dysrhythmia

Several major changes in the mid-2000s ushered in the death of such regular price cycles. The U.S. quickly found itself part of the global market. The explosion of prices on the world market encouraged the U.S. to begin supplying large amounts of exports to the international market with no need for help from the government through subsidies.

U.S. prices were suddenly heavily influenced by developments in the global market as a result, ending decades of domestic isolation. Click here or on image at right to view it at full size in a new window.

U.S. prices were suddenly heavily influenced by developments in the global market as a result, ending decades of domestic isolation. Click here or on image at right to view it at full size in a new window.

While attractive for many reasons, the world market which the U.S. had exposed itself to was extremely diverse and unpredictable as well. This diversity and unpredictability has long precluded anything that resembles the regular pricing cycles U.S. dairy producers had long become accustomed to.

At home, the advent of higher and more volatile feed prices drove a wedge between the costs of those producers buying in feed versus those who grew it themselves, destroying the homogeneity of the local supply base.

This price dysrhythmia won’t change the fact that there will be periods of rising prices followed by periods of falling prices. Also remaining the same will be the lagged nature of supply response to pricing. What will be most affected is that periods of high and low prices are likely to be less regularly interspersed than the industry has been accustomed to for most of the last 20 years.

Fluctuating feed costs don’t make it easier

Owning and operating a successful dairy operation has never been easy, but throughout the history of the U.S. dairy market, there has been a significant level of stability with producer margins compared to milk prices. In the past, if producers wanted to purchase feed, it roughly penciled out to be the same costs as growing their own corn, soybeans or hay.

As such, dairy producer margins were typically revenue-driven, simply rising and falling with the milk prices they received. Since 2007, however, feed prices have lost their stability and short-term shifts in the cost of feed no longer parallel milk prices – with revenue and costs at times moving in opposite directions.

A new approach

With a regular pricing cycle no longer the standard for dairy, those who buy milk and dairy commodities can no longer afford to base their planning and risk management on such a predictable cycle. Instead, when planning price expectations, they should look beyond the borders of the U.S., taking into account the unpredictability of the world market.

While the U.S. maintains an important position in the global marketplace, there are several other regions that influence U.S. pricing. Understanding the forces at play, at least in the main regions of influence, is crucial for any useful price forecasting.

For dairy producers, risk management is key to sustaining an operation through new, unpredictable price cycles. One set of tools for achieving this revolves around locking in the prices of milk and feed through the use of listed futures contracts and/or forward contracts. Unfortunately, lack of market liquidity means the opportunity to do so profitably via listed contracts appears less often than the market might warrant.

Upstream vertical integration to internalize feed production is another option that may help stabilize feed costs, though it requires considerable capital, introduces more production risk to the business and covers only the cost side of the business.

More generally, producers can set aside more working capital to help weather the volatility that they cannot control (or find too expensive to do so). None of these approaches on their own offer a perfect solution to managing price volatility – and the best strategy will vary from business to business. But finding a way to survive this volatility is a precondition for long-term survival in the U.S. dairy industry. PD

Tim Hunt is an executive director with Rabobank’s Global Food & Agribusiness Research and Advisory unit and leader of the unit’s global dairy sector team.

Tim Hunt

Rabobank