The goal of any forage program for a dairy is to grow and harvest the highest-quality feed for the cows.

Once the forages are ready to be harvested and stored, that’s when the farmer and nutritionist start to plan the feeding program for the year. The first step is to calculate the amount of forage that can be fed to allow inventory to last 12 to 15 months. If you have the inventory to feed high-forage diets, start formulating a high-production diet.

When feeding high-forage diets with high production in mind, success comes down to the details – from how the forages were stored to formulation strategies to reduce variation and maximize production. This starts with the planning of forage storage and testing of samples from different fields. Sampling of the forage can be done in the field or at the bunk as new loads come in. It is ideal to get a representative sample by collecting subsamples from each load and mixing them to get the representative sample. Collecting samples can pose a danger, as large equipment is moving around, so be sure to wear a high-visibility vest and make sure the large-machinery operators see you.

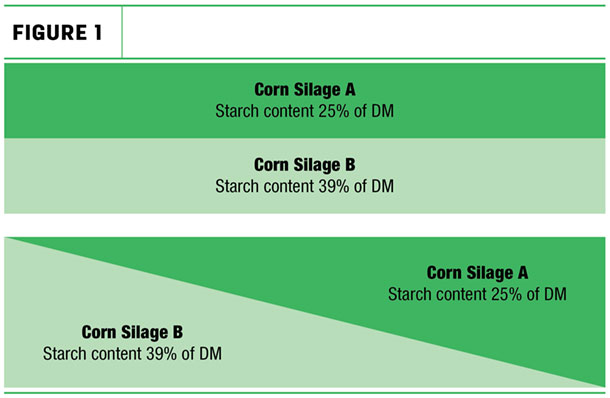

As you feed more forage such as corn silage or haylage, the variation in these feeds will become even more prominent in cows’ performance – so planning how you will store the forages will dictate how smoothly you can transition between them. For instance, if you are filling a corn silage bunker with “corn silage A” which has a starch content of 25% of dry matter (DM) and “corn silage B” which has a starch content of 39% of DM, there are a couple of ways to fill the bunk.

Figure 1 shows two ways to fill the bunker, with the top schematic showing a layering process and the bottom schematic with a wedge system.

The layering of the different corn silages will allow for an even mixture of the two, so the corn silage going into the mixture would have a starch content of 32% of DM. In the wedge system, as you feed into the bunk, it can change 14 percentage units of starch from one side of the bunk to the other. If you are feeding 26 pounds of DM of corn silage in the diet and are feeding mainly corn silage A, you would be providing 6.5 pounds of starch from that corn silage. If you feed mainly corn silage B, then you would provide 10.14 pounds of starch. This is a large difference in provided energy, but both systems can be fed with minimal interruptions in cow performance with proper sampling.

To get the most out of your forages, it is important to understand what can hinder fiber digestion, such as rumen pH and mycotoxins. As the diet’s forage content increases, the greater the importance of rumen dynamics such as digestion and passage rate. In a high-forage diet, the goal is to have the forage particles hydrate and start digesting as soon as possible or have a relatively short lag time. This allows the particle to reach the critical particle size needed to pass from the rumen. It has been shown for decades that low rumen pH can depress fiber digestion. A Journal of Dairy Science article from researchers at the University of Nebraska reported that low pH induced by addition of starch in an in-vitro system caused a decrease in the digestion rate and longer lag time. Low pH increased the time for fiber digestion to initiate, slowed the rate of fiber digestion and decreased the extent of fiber digestion, and this will negatively affect intake by increasing the residence time of fiber.

Fungi can grow on forages in the field or in storage. They can create mycotoxins that cause negative consequences for the dairy cow by reducing intake, milk production and fiber digestion. In high-forage diets, it is important to either test for mycotoxins or use a mycotoxin binder to mitigate the negative effects. One of the herds I am the nutritionist for switched into a new haylage pile that, unbeknown to us, had a significant mycotoxin load. It took seven days of feeding the new haylage until the farm lost 3.5 pounds of milk per cow per day. We added a mycotoxin binder, and within seven more days, we had gained back the 3.5 pounds lost. This is one of the more extreme cases, but even low levels of mycotoxins can cause reductions in performance.

The goal of high-forage diets is to utilize homegrown forages to reduce purchased feed costs. It takes a lot of work to get high milk production from high-forage diets. When harvesting forages, it is vital to know where the different cuts of haylage or fields of corn silage are stored so a plan can be made to feed them with minimal effects on performance. Once you know how you will feed the forages, it is important to make sure we mitigate any negative effects on fiber digestion by keeping fermentable carbohydrates at a reasonable level or having a mycotoxin binder in the diet. Each farm has its own unique challenges and will need a system to achieve high-forage diets that allow for high production.

References omitted but are available upon request by sending an email to the editor.