Inadequate blood calcium concentrations at this time can result in the metabolic disorder hypocalcemia or low blood calcium.

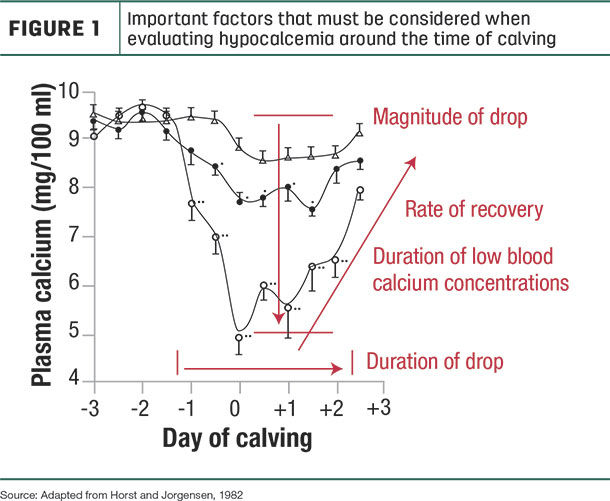

There are three important factors that must be considered when evaluating hypocalcemia around the time of calving (Figure 1):

1. The magnitude of the drop in blood calcium concentrations

2. The rate by which blood calcium concentrations recover to normal levels

3. The duration of low blood calcium concentrations

Increasing a cow’s resistance to hypocalcemia can decrease the magnitude and shorten the duration of low blood calcium concentrations as well as speed the recovery to normal blood calcium levels.

To improve a dairy cow’s resistance to hypocalcemia, the cow must be able to replace calcium in its bloodstream quickly. Calcium homeostasis is primarily controlled by the parathyroid glands. Parathyroid glands respond to changes in blood calcium concentrations. When large amounts of calcium leave the blood (like during colostrum and milk synthesis), parathyroid glands respond by releasing parathyroid hormone (PTH).

The main function of PTH is to increase blood calcium concentrations. It does this in two main ways.

First, PTH stimulates the resorption (or breakdown) of bone. This process releases calcium into the bloodstream. Second, PTH assists in the production of the active form of the hormone vitamin D (1, 25 dihydroxyvitamin D), which helps increase the absorption of calcium from the diet in the digestive tract.

In the intestine, calcium is absorbed from the diet into the cow’s bloodstream by two different pathways: a vitamin D-dependent pathway (meaning vitamin D is required for this process to occur) and a vitamin D-independent pathway (vitamin D is not required).

Vitamin D-dependent calcium absorption is also known as the “active transport” pathway. This pathway is the predominant route of calcium absorption when dietary calcium is low or when the demand for calcium is very high, like around the time of calving in dairy cows. Vitamin D is crucial for the active transport of calcium across intestinal cells and into the bloodstream.

Vitamin D-independent absorption of calcium occurs via passive diffusion. Passive diffusion is the movement of substances from a higher concentration to a lower concentration without the need of energy. Passive diffusion occurs when dietary calcium concentrations are high, like when high-calcium diets are fed. Calcium diffuses through the tight junctions that connect intestinal epithelial cells and then into the bloodstream.

Dairy cows replace blood calcium around the time of calving by increasing bone resorption to liberate more calcium from the bone and by the absorption of dietary calcium in the digestive tract using both vitamin D-dependent and -independent calcium absorption pathways.

University research examines fully acidified high-calcium prepartum diets

Since the 1970s, EDTA has been used in research studies to induce hypocalcemia in dairy cows, as it chelates (or binds) calcium and magnesium. By binding calcium, EDTA simulates the large demand for calcium that occurs around the time of calving. More recently, scientists have begun to use EGTA instead of EDTA, as EGTA binds calcium only and therefore more accurately mimics what is occurring physiologically in the dairy cow.

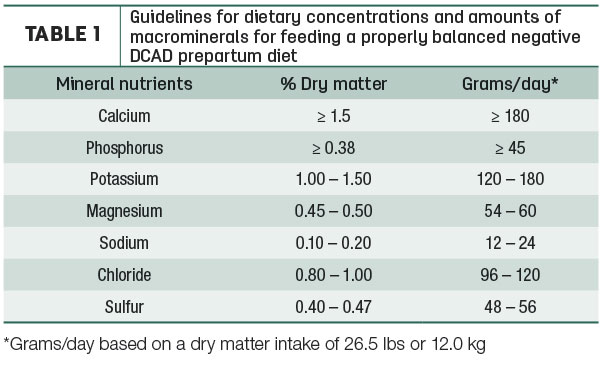

Feeding supplemental anions to achieve a diet with a negative dietary cation-anion difference (DCAD) during the prepartum period is a common preventative method used to reduce hypocalcemia, leading to improved start-up milk and overall lactation performance in dairy cows. Fully acidified negative-DCAD diets contain supplemental anions at a rate to maintain urine pH in the range of 5.5 to 6.0 and should be fed for at least 21 days prior to parturition.

In a recent University of Wisconsin study, non-pregnant, non-lactating Holstein cows were fed fully acidified diets with either low (0.45%), medium (1.13%) or high (2.02%) concentrations of calcium for 21 days prior to an EGTA challenge. EGTA was administered intravenously to induce hypocalcemia.

Cows fed the fully acidified high-calcium diet had higher mean blood ionized calcium concentrations over the 21-day feeding period and the EGTA infusion period. These cows also took longer (more minutes) and required more grams of EGTA to achieve hypocalcemia than cows consuming either the low- or medium-calcium diets, indicating increased resistance to the induction of hypocalcemia.

The rate of recovery from hypocalcemia was not altered by dietary calcium concentration, but improved resistance to hypocalcemia with fully acidified high-calcium diets suggests recovery can begin sooner with these diets, which can shorten the duration of low blood calcium concentrations during the early post-calving period. These data suggest that feeding high dietary calcium in combination with a fully acidified negative-DCAD prepartum diet may provide more biologically active calcium during the periparturient period when the demand for calcium is high.

The effects of feeding fully acidified high-calcium diets were also examined in a University of Illinois study using transition cows. This trial compared a traditional low-calcium diet, a fully acidified low-calcium diet and a fully acidified high-calcium diet. Both fully acidified diets successfully improved blood calcium concentrations around the time of calving, as well as postpartum intakes and milk production when compared to the traditional low-calcium diet. However, cows fed the fully acidified high-calcium diet also had increased prepartum intakes compared to cows fed the fully acidified low-calcium diet.

Summary

1. University research demonstrates that feeding fully acidified high-calcium diets before calving improves the health and performance of dairy cows after calving.

2. Fully acidified high-calcium prepartum diets may allow dairy cows to more quickly replace blood calcium around the time of calving by increasing bone resorption and absorption of dietary calcium in the digestive tract.

3. Improved resistance to hypocalcemia can decrease the magnitude of the drop in blood calcium concentrations at calving, allowing the recovery to normal blood calcium levels to begin sooner, which can shorten the duration of hypocalcemia. ![]()

Laura Hernandez is an associate professor at the University of Wisconsin – Madison.

References omitted but are available upon request. Click here to email an editor.