Fat mobilization includes lipogenesis and lipolysis. Lipogenesis is the assembly of triglycerides from fatty acids and glycerol. During lipolysis, fat cells’ enzymes break down the triglyceride molecule and release fatty acids as NEFA (non-esterified fatty acid).

During the transition period, low dry matter intake (DMI) and high energy needs driven by parturition and the onset of lactation promote lipolysis and reduce lipogenesis in fat cells. As a result, NEFAs are released into the blood. Normally, lipolysis decreases and lipogenesis replenishes fat depots’ triglyceride reserves as lactation progresses. However, cows that mobilize too much fat will become more susceptible to diseases such as ketosis, displaced abomasum and fatty liver.

Lipolysis induces inflammation

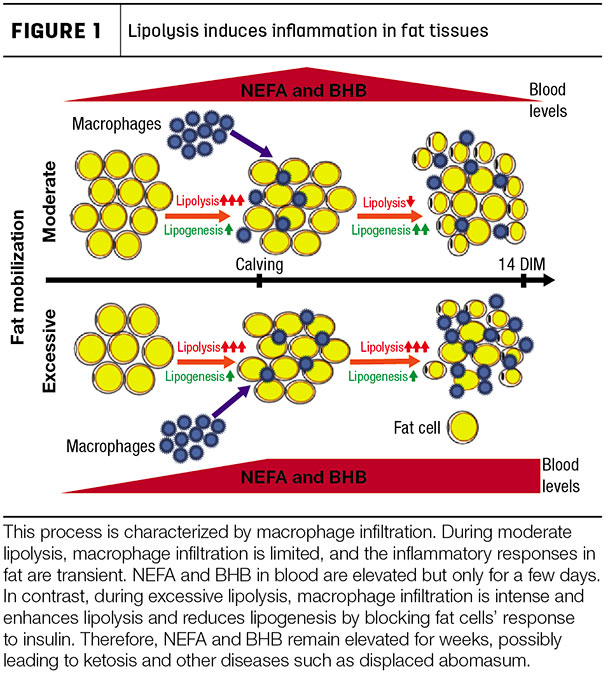

The consequences of enhanced lipolysis and reduced lipogenesis in fat of transition cows go beyond the release of NEFA into circulation. Lipolysis also induces an inflammatory response in fat that is characterized by infiltration of immune cells, especially macrophages (see Figure 1). In healthy transition cows that have moderate lipolysis, macrophages account for less than 1 percent of the total number of cells in fat tissues. However, in cows that mobilize too much fat, such as those with ketosis, macrophages account for greater than 3 percent of the total number of cells in fat.

A moderate infiltration of macrophages into fat is beneficial as these cells clean up the fat tissues from the toxic products that lipolysis produces, including NEFA, diglycerides and monoglycerides. Excessive infiltration of macrophages, however, will increase inflammation and further promote lipolysis. This is because fat macrophages secrete potent blockers of insulin function. In addition, excessive lipolysis also impairs the function of blood immune cells. For example, high NEFA concentrations reduce the capacity of blood leukocytes to kill and clear invading pathogens, impair the production of antibodies and slow down their migration to sites of infection. Therefore, transition cows with high lipolysis may be more susceptible to mastitis and metritis.

Modulating lipid mobilization in the transition period

A basic management and nutritional strategy that reduces lipolysis and promotes lipogenesis in the transition period is maximizing DMI. In addition, it is necessary to limit the sudden drop in feed intake commonly observed during the final weeks of the dry period. It is also imperative to balance prepartum diets to meet but not exceed energy requirements. This is usually accomplished by feeding high levels of fiber.

When balancing rations for dry cows, it is necessary to consider that overfeeding energy in the last weeks of gestation enhances lipolysis postpartum and increases the risk of fatty liver. Cows that gain excessive body condition during the dry period have larger fat cells that are more sensitive to lipolysis stimuli at calving and early lactation.

To complement ration balancing strategies, the inclusion of nutritional supplements that limit lipid mobilization in the diet of transition cows can be considered. Feeding niacin (as nicotinic acid) reduces adipose tissue lipolysis by blocking the activation of the enzyme that breaks down triglyceride molecules, hormone-sensitive lipase. In order to be effective, niacin needs to be fed throughout the entire transition period in order to reduce lipolysis effectively.

Evaluating lipid mobilization during the transition period

Body condition score (BCS) is a good measure of subcutaneous fat, and the reduction in BCS after parturition is a reflection of lipolysis rates. Mature cows should approach calving with a BCS of 3.0 to 3.5 and heifers with 3.25 to 3.75, as excessively thin or overconditioned cows are more susceptible to disease. Mature cows should not lose more that 0.5 BCS points during the first month after calving.

Lipolysis is also measured indirectly by the concentration of plasma NEFA and beta hydroxybutyrate (BHB). Ideally, during the first week of lactation, cows should have NEFA values of less than 500 millequivalent per liter (mEq/L) and BHB concentrations below 12.5 milligrams per deciliter (mg/dL). The rate of lipolysis can also be evaluated at the group or individual animal level using the milkfat-to-milk-protein percentage ratio. Milkfat increases as plasma NEFA rise. Cows with milkfat-to-milk-protein ratio values higher than 2 during the first week after calving are at a higher risk for developing retained fetal membranes, a displaced abomasum, clinical endometritis and being culled before the end of lactation.

It is necessary to note that a single marker of lipid mobilization does not provide enough information to support management decisions during the transition period. However, when multiple markers are analyzed together and combined with health, production, nutritional and environmental data, it is easier to identify metabolic problems related to extended periods of intense fat mobilization.

In conclusion, excessive fat mobilization around parturition promotes inflammation in fat tissues that triggers a vicious cycle where excessive lipolysis can exacerbate fat inflammation, which in turn further intensifies lipolysis and reduces lipogenesis. ![]()

-

Andres Contreras

- College of Veterinary Medicine

- Michigan State University

- Email Andres Contreras