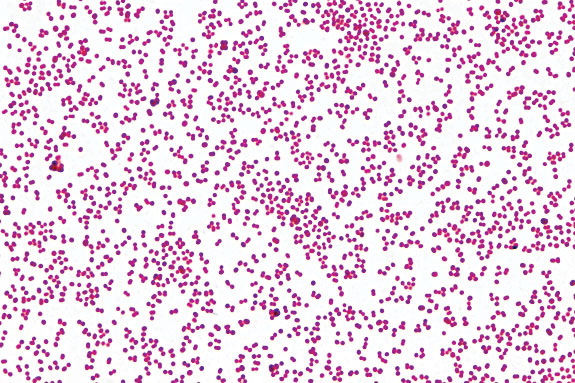

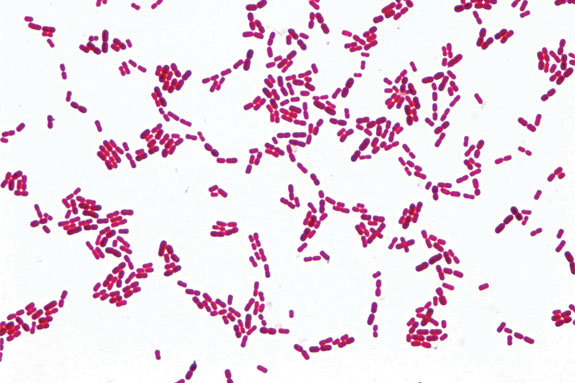

M. ovis is a spherical-shaped (coccoid) organism as opposed to the typical short “rod-shaped” Moraxella bovis.

For a number of years, Addison Biological Laboratory’s diagnostic laboratory has been reporting isolations of spherical Moraxella species isolated from cases of bovine pinkeye as coccoid M. bovis.

In genetic analyses of these organisms we found that they were 97 percent identical to M. bovis and less similar to M. ovis; therefore, we believed these were a natural variant of M. bovis.

In 2007, Drs. Angelos and George (et al.) at the School of Veterinary Medicine at the University of California-Davis, reported that these spherical-shaped Moraxella organisms from cattle pinkeye cases represented a new species of Moraxella, Moraxella bovoculi.

One reason for renaming this species is to clear up the prevalent confusion in our industry, so we can treat the disease with consistency and accuracy.

Another reason is that there are currently no federally licensed, commercially available M. bovoculi vaccines.

In a university herd of beef calves, Dr. John Angelos found that M. bovoculi could be isolated more often from pinkeye-affected calves that had been vaccinated with M. bovis proteins compared to control (unvaccinated) calves.

Likewise, M. bovis was more often isolated from pinkeye-affected calves vaccinated with M. bovoculi proteins compared to control (unvaccinated) calves.

These observations suggest that in herds where both M. bovis and M. bovoculi are present, it may be important to vaccinate for both organisms.

We often culture cattle eyes with typical pinkeye lesions and isolate both M. bovis and M. bovoculi.

Of the bovine eye culture cases examined by our diagnostic laboratory from active pinkeye herds in 2010, we found only M. bovoculi in 42 percent, only M. bovis in 12 percent and both M. bovis and M. bovoculi in 26 percent. It should be noted that many of these herds had previously been vaccinated for M. bovis, which could explain why there were many more cases with M. bovoculi only.

Another important distinction is the susceptibility of these organisms to commonly used antibiotics. In our diagnostic laboratory we have found that M. bovis is still relatively sensitive to the antibiotics commonly used to treat pinkeye.

But M. bovoculi appears to be significantly less sensitive to the commonly used antibiotics. I often wonder how often we have clinical pinkeye that would yield a mixed M. bovis and M. bovoculi but after a “failed” round of antibiotics, we only isolate M. bovoculi due to its antibiotic resistance.

While I often recommend Tetracyclines for treatment of pinkeye, we found that of the M. bovoculi on which we ran sensitivity testing, 37.84 percent were not sensitive to Tetracyclines.

For these reasons it’s important to have a reputable laboratory culture the eyes of animals with clinical pinkeye, especially if the herd has been properly vaccinated with commercial M. bovis vaccine.

It’s also wise to request an antibiotic sensitivity test if your laboratory isolates M. bovoculi. It is expensive and frustrating to administer antibiotics to cattle and see no results due to an ineffective antibiotic.

Other than the differences discussed above, we assume that M. bovoculi and M. bovis affect cattle in very similar ways. To minimize the effects of pinkeye disease in cattle operations, we should review the following information.

Managing pinkeye in cattle herds

Pinkeye refers specifically to the bovine eye disease caused by Moraxella bovis, Moraxella bovoculi or a mixed infection of the two (referred to as Moraxella spp).

Since the bovine eye can only respond in a limited number of ways to disease or injury, there are many times when a case may be perceived as pinkeye yet not involve Moraxella spp.

Pinkeye is considered the most important ocular disease of cattle. Economic losses from pinkeye have been estimated up to $200 million annually in the U.S. alone.

This estimate is based on lack of gain in feedlots and on greatly diminished weaning weights (25 to 40 pounds per head) in calves.

Clinical signs of pinkeye

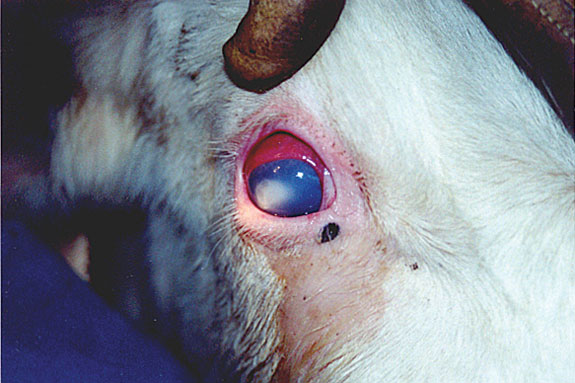

The disease starts with eye(s) tearing. Tearing is usually very evident from the inner corner of the eye and cattle will often squint in the affected eyes.

Usually within a day of the start of tearing, close examination of the eye will reveal pits (1/16 of an inch or larger) called lesions or ulcers of the surface (cornea) of the eye.

Over the next few days these may enlarge, the eye may turn blue and then white. There may be a blood-red border around these ulcerations.

In severe cases, the surface of the eye may become cone-shaped and may rupture. Animals affected this severely in both eyes can become blind.

Blindness can often be prevented with early treatment and simultaneous vaccination (revaccination). Pinkeye normally starts with one or two animals and may quickly spread to the other animals by face flies or direct contact.

Usually within two weeks of the initial case, the herd outbreak will be at its most severe stage. Recovered cattle may have blue to white scars on their eyes and eye surfaces may be enlarged or misshapen.

Pinkeye can occur at any time of year, but it is primarily seasonal with the greatest occurrence linked to exposure in peak periods of ultraviolet light irradiation.

Most outbreaks are associated with a number of predisposing factors that are very important to consider in managing and preventing outbreaks.

Predisposing Factors

• Age of cattle: Younger cattle are more susceptible to pinkeye than older cattle.

• Ultraviolet irradiation (bright sunlight) has been demonstrated to aid corneal colonization by Moraxella spp. and microscopic examination has shown the cell damage initiated by UV burning.

• Viral infection (e.g. IBR virus) is capable of damaging the protective cells covering the eye, not only on the cornea, but also on the eyelids.

• Physical trauma such as blowing dust and sand, weed seeds and stubble, face flies, tail switching, antibiotic powders, etc., can scratch the cornea and allow entry of Moraxella spp.

• Chemical trauma such as fresh nitrogen on the pasture can burn the protective cell layer.

• Stress from shipping, processing, insects, etc., can be very immunosuppressive.

If we keep in mind that pinkeye caused by Moraxella spp. is a very contagious disease, it helps explain the method of spread and how to practice more effective control measures.

The bovine eye, nasal passages and sometimes the vagina are where the organism resides and presumably overwinters.

Pinkeye breakouts usually occur two to three weeks after processing in the spring.

If the organism can be shed in high numbers in tears or nasal secretions and the animals are crowded and extremely stressed during processing, we have all the right circumstances for the spread of disease in general and pinkeye in particular.

It is not known how long Moraxella spp. can survive in the body secretions or on environmental surfaces, but it has been known to survive for up to three days on the feet of a face fly and, therefore, we should assume that all surfaces contaminated by infected animals (crowding chutes, clothing, instruments, trailers and barn walls) are potential sources of disease for at least several days.

Due to this contagious nature, handlers should be aware that contamination on their clothing, hands, ropes, etc., may be capable of transferring infectious agents during processing. Insects, especially face flies, should be considered to be mechanical vectors.

Aerosols (sneezing) have been incriminated in the spread of Moraxella spp. and should not be ruled out as possible modes of transmission as cattle carry high numbers of organisms in the nasal passages.

Treatment of pinkeye

When animals are run through the chute for pinkeye treatment, we should do everything possible while the animal is being restrained to prevent having to get that patient up again.

Common treatment procedures include: antibiotic therapy, either topically, eyelid injection or intramuscular. Topical application is easy to do, but it is difficult to maintain effective levels of topical antibiotics in the face of heavy tearing.

From a purely psychological view, many cattlemen seem to feel better when the cow has “purple stuff” on its face because they can see that they have at least done something for their animal.

IM injection of antibiotics, such as long-acting tetracycline, has the added advantage of helping to reduce the numbers of M. bovis in other tissues in the body as well as the eye.

Protecting the eye from sunlight and other irritants may accelerate healing as well as make the patient more comfortable. Sutures, eye patches and isolation in a dark barn are all options to be considered.

Vitamin A can be injected, and nutritional deficiencies especially copper and selenium should be addressed.

Vaccination with an M. bovis bacterin may boost the antibody response in previously vaccinated animals. Significant improvement in pinkeye cases have been observed as quickly as three to five days post-vaccination. I strongly recommend vaccination/revaccination when treating active pinkeye cases.

Prevention

Minimizing predisposing factors can be very helpful. Pay attention to fly control programs, clip pastures, perform forage analysis to help ensure adequate nutrition, provide shade and pay attention to the fact that we are dealing with a contagious disease.

Vaccination for M. bovis with some of the newer vaccines has proven to be very advantageous.

Pinkeye is an economically important disease in cattle worldwide. Having a more thorough understanding of pinkeye and educating ourselves on treatment and control measures can play an important role in positively impacting the profitability of raising cattle. ![]()

References omitted due to space but are available upon request.

PHOTOMICROGRAPHS and PHOTOS

Top: The tiny pink circular dots are the spherical-shaped Moraxella bovoculi.

Middle Top: The tiny rod-shaped organisms are typical Moraxella bovis. Images courtesy of Addison Labs.

Middle Bottom: Shows a typical eye that has pinkeye.

Bottom: Shows a normal eye. Photos courtesy of Addison Labs.

Bruce Addison

President

Addison Labs

baddison@addisonlabs.com