Inspired beginnings

Barten was inspired to begin his company while doing embryonic work with his brothers at Bluestem Embryo Transfer Center, a company they founded. Some of their clients were having issues with developmental duplication in their animals.

“I saw they had good donors at the time that weren’t being used for assisted reproductive technologies anymore because they had one bad gene,” Barten says. “I saw an opportunity to maybe help them out.” With the ability to know the exact genotypic information at the earliest possible stage, problem animals can be identified and removed before the pregnancy even took place.

For Barten, who hails from a cow-calf operation in Kansas, his work is a way to marry his two loves of ranching and genetics. “I’ve always liked cattle, and I’ve always liked trying to pick the best genetics to breed animals to,” he says.

“I get to still be up to date on genetics, I get to have some wonderful conversations with the clients I have – I get to really help them out.”

Embruon works in collaboration with NeoGen’s GeneSeek. Barten has the embryos biopsied at his facility in Salina, Kansas. The resulting cells are sent to GeneSeek where the DNA is extracted and then amplified until it is sufficient for genotyping, a process that takes four to five days.

“The concept of taking an embryo biopsy … to be able to get an estimate of genetic merit is a very natural extension of the work we do every day,” says Dr. Stewart Bauck, general manager at GeneSeek. The partnership is essential to the success of both parties meeting the needs of individual producers.

A battle of odds

Getting an embryo through collection, biopsy, healing – and successfully transferred – isn’t an easy process. “That’s one thing I’ve learned is patience,” says Barten. “This stuff is really hard. It takes longer than you think it should. But to do it well, to do it the right way, is going to take some time.”

Clients can collect embryos 24 hours early and ship them overnight to Salina in a culture media. When they arrive, they wait for the optimal time to conduct a successful biopsy. “We don’t biopsy a group of embryos just because they’re in front of us,” Barten says. “We try to biopsy when the timing matches the embryo best.”

After biopsying, the embryos need time to properly heal or “anneal” as the self-repair process is called. They do their best to mold the process around the embryo so it has its best chance to heal and grow into a viable calf. “Genomics is great,” he adds. “But if it doesn’t make a pregnancy at the end, it’s not worth it.”

With all the work involved, you want to maximize the odds of success to the fullest possible extent. Barten utilizes a risk analysis model that generates an overview of IVF and embryo transfer programs using a stochastic simulation. This extra step helps account for the biological uncertainty that comes with reproduction.

The model was developed by Dustin Aherin, a recent graduate of Kansas State who is working towards his doctorate. “The idea behind this model is that all these variables can be changed based on a specific scenario or program or historical situation you may have,” says Aherin. “You can make individualized scenarios to see how one strategy might change its results from one operation to the next.”

Similar systems are already used in other industries, and Aherin points to the delay in livestock due to the complexity of biologic variability. Taking a computerized approach to a difficult concept, he explains, is powerful because it’s easier to understand than complicated handwritten math.

“It forces us to take an objective point of view and put some hard numbers to different things, see how the whole system interacts and what the results of that are,” Aherin says. “It gives us a tool to take one step away from speculation and move a little bit closer to self-predictive analysis.” Barten, with Aherin, uses this model in webcam meetings with their clients to help aid in the decision-making process.

Tomorrow’s technology

As Angus producers already know, the American Angus Association (AAA) deployed the single-step method to combine genomic data with their EPDs and dollar-value indexes this past July. With the stage set to utilize genomic technology better than ever before, AAA’s board of directors has agreed to extend their GE-EPD registry to include these embryos.

“This is just another tool in the tool belt for their members,” says Barten. While AAA is the only association currently involved, Barten notes they are open to others joining them.”

“Obtaining genomic data on animals very early on has the capability to narrow the wide generation interval that historically disadvantaged genetic improvement in the beef market. “What cattle can accomplish with the tool of genomics,” Barten says, “levels the playing field in the other protein market. We can make better decisions while shortening that generation interval.” Genotyping also has cost benefits.

The process only costs around $140 an embryo with all the decision-making information you need at your fingertips. “The great news is; essentially, instead of waiting until birth, I can get an estimate of genetic merit at minus 9 months,” says Bauck. “I can determine the sex, I can determine the genetic merit, I can determine the freedom from or absence of various defects and so forth. Just like you would do prenatal screening in a human, we can do essentially the exact same thing here.”

Barten points out that by the time a calf is on the ground, it could already be a $2,000 investment – a major cost for an animal that may not be what you want. “The more decisions you can make earlier on in the process is well worth it.”

Genotyped embryos have a lot of potential to be the next big player in livestock breeding. Bauck attributes the improvement of embryo viability after handling to be essential in advancing this technology in the mainstream industry.

“When we first started using some of these technologies and using embryo manipulation, our capability to do embryo manipulation was not what it is today. The loss of pregnancy associated with manipulating embryos was enough that it kind of turned people off,” he says. “We’re better at what we do, so we get much better accurate results on our side.”

While still at its early stages of entering the commercial market, it’s definitely worth watching for in the very near future. “I’ve seen it become more and more mainstream just in the three years I’ve been involved with it,” Barten says. “It’s still an uncreated market, but with the adoption of genomics, I feel that there will soon be one.” ![]()

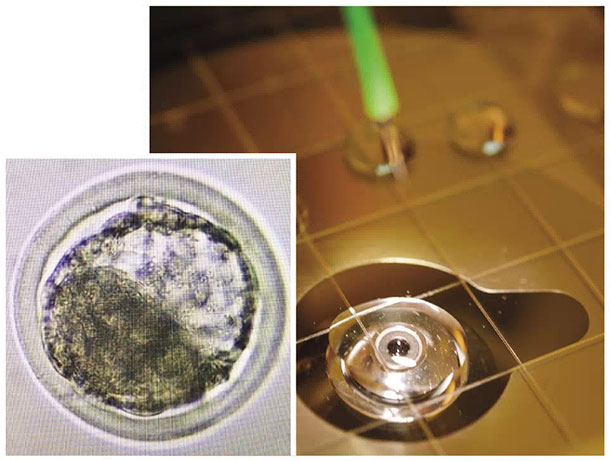

PHOTO 1: Matt Barten biopsies embryos at his lab. The process involves taking a few cells from an embryo and giving it time to anneal or self-heal. Photo by Jim Patrico/DTN-The Progressive Farmer.

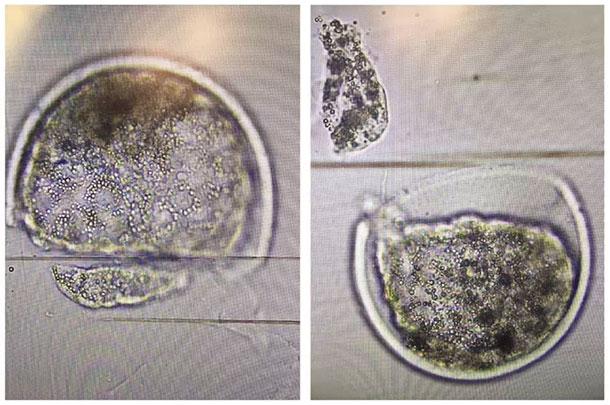

PHOTO 2: A biopsied cell has been removed from the embryo proper at 6 o’clock. These are trophectoderm cells or cells that become the placenta. At the 10 to 1 o’clock range, shown with the darker cells, you can see the inner cell mass or cells that become the fetus. BOTTOM: In this biopsy picture, the embryo is just laying in the opposite direction. In embryo biopsy, you have to work with the embryo.

PHOTO 3: In this post-biopsy picture, this embryo is annealing or self-repairing. This is evidenced by the re-expansion of the blastocoele, or fluid-filled area, that was collapsed as a result of biopsy. RIGHT: A biopsy blade sits over a drop of splitting medium. The embryo sits in the drop for biopsy. Photos provided by Matt Barten.

Jaclyn Krymowski is a freelance writer based in Ohio.

-

Jaclyn Krymowski

- 2017 Editorial Intern

- Progressive Cattleman

- Email Jaclyn Krymowski