The age-old question remains: Is there an “efficient” range cow? And, to further complicate that question, you could open a can of worms by also asking: What efficiency are you measuring? Efficiency is output divided by input. When discussing beef cattle efficiency, this is usually measured with feed intake. Simply put, efficiency is how much is this animal going to produce divided by how much input (feed, management etc.) you put into it. To answer this question and discover if there are indeed cows better suited in a range environment, the University of Idaho conducted a study.

The objective of the study was to characterize the forage intake of 24 head of 2-year-old lactating cows at both mid and late lactation while grazing rangeland at Rinker Rock Creek Ranch in June and August of 2016. This herd of 24 cows had previously been classified as either efficient (ate less than expected for the weight and growth) or inefficient (ate more than expected, greater appetite). To classify these cows, they were fed as yearling heifers using a Growsafe system, which measures the quantity of feed a cow eats every day. Cattle with negative residual feed intake (RFI) scores consume less feed than expected and are classified as more efficient, while cattle with positive RFI scores consume more feed than expected and are classified as inefficient.

Twelve cows in the herd were efficient and 12 were inefficient. To determine their intake, six gelatin boluses were administered orally at the start of the trial period. The boluses consisted of shredded filter paper with C32 alkane impregnated onto them. The release of the alkane marker into the lower tract was measured over the next four days. Fecal samples were collected from cows as they grazed over a four-day period in an 80-acre pasture. From dawn until dusk, a team of five people followed the 24 cows, collecting fecal samples as they were deposited. When samples were collected, the cows’ ID and time of collection were recorded with each sample.

A team of five people followed the 24 cows from dawn to dusk, collecting fecal samples as they were deposited and recording the cows’ ID and time of collection. Courtesy image.

After working through the data, reliable estimates of intake with the pulse dose were obtained. Yet, there was no difference in the intake of the efficient and inefficient cows. The herd of cows averaged 1,020 pounds and consumed between 2.4%-2.9% of their bodyweight in forage. However, there were some interesting results garnered from the study. As would be expected, the feed quality of the forage declined from June to August, which also caused an increase in retention time. In June, the forage quality was 59% digestible with a rumen retention time of 39 hours, and in August the forage digestibility was 54% with a retention time of 44 hours.

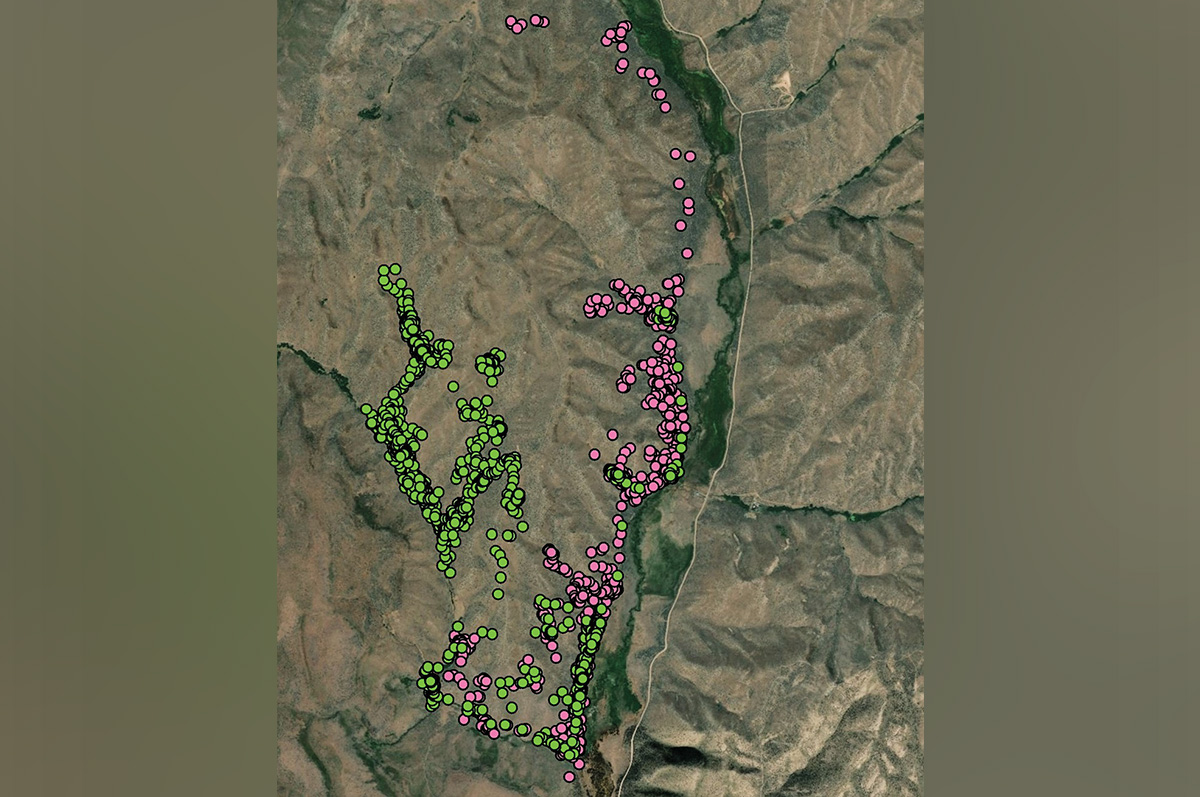

Total grazing time was determined using grazing collars with accelerometers and GPS. Grazing time increased from 10.1 hours per day in June to 10.7 hours per day in August. Additionally, the study found that when temperatures were hot in August, efficient cows climbed higher on the slopes than inefficient cows and started grazing earlier in the late afternoon. The study hypothesizes that cattle with greater appetites have a larger gastrointestinal tract, which generates more metabolic heat load. Think of it in comparison to a vehicle that contains a 454 gasoline engine versus an air-cooled aluminum block engine.

GPS data showing that, during hot August days, efficient cows climbed higher on the slopes than inefficient cows and started grazing earlier in the late afternoon. Courtesy photo.

The researchers also worked with a molecular geneticist to analyze DNA in our experimental cattle to look for genetic markers related to terrain use and grazing behavior. Although they did not specifically tie grazing behavior to efficiency status, researchers did find five gene marker regions that related to terrain use and grazing behavior, explaining 43% to 52% of the animal variance for grazing time, walking time, maximum slope and time spent on slopes greater than 15 degrees. These preliminary results, combined with other data from Dr. Derek Bailey from New Mexico State University, suggest that producers may be able to select replacement heifers that more effectively use steep terrain and fit rugged rangeland grazing systems using DNA technology.

All of this does not say whether there are efficient or inefficient cows best suited for rangeland. Any good rancher can tell you what cows in their herd perform better on rangeland than others and likely have a very detailed list of reasons why. However, researchers have not found the best way to measure this efficiency in the feedlot that then translates to the range … yet. There are other measurements and markers being studied to answer this question to aid ranchers and cattle producers in their selection criteria. As the literature and research build on this subject, we hope to have more answers on how to best select cattle that are most efficient in a rangeland setting.

The authors would like to acknowledge Dr. Brenda Murdoch of the University of Idaho and her graduate student Morgan Stegemiller for their analysis of the DNA samples of these experimental cattle.