Have you ever found a good deal on a product, or an off-brand product, and hurried to make the purchase, only to have the item quickly break or underperform? We all like the idea of getting more for less, whether it be in our personal lives on a regular trip to the hardware store or making a big purchase on the farm. However, sometimes the deal isn’t worth the sacrifice in the long run.

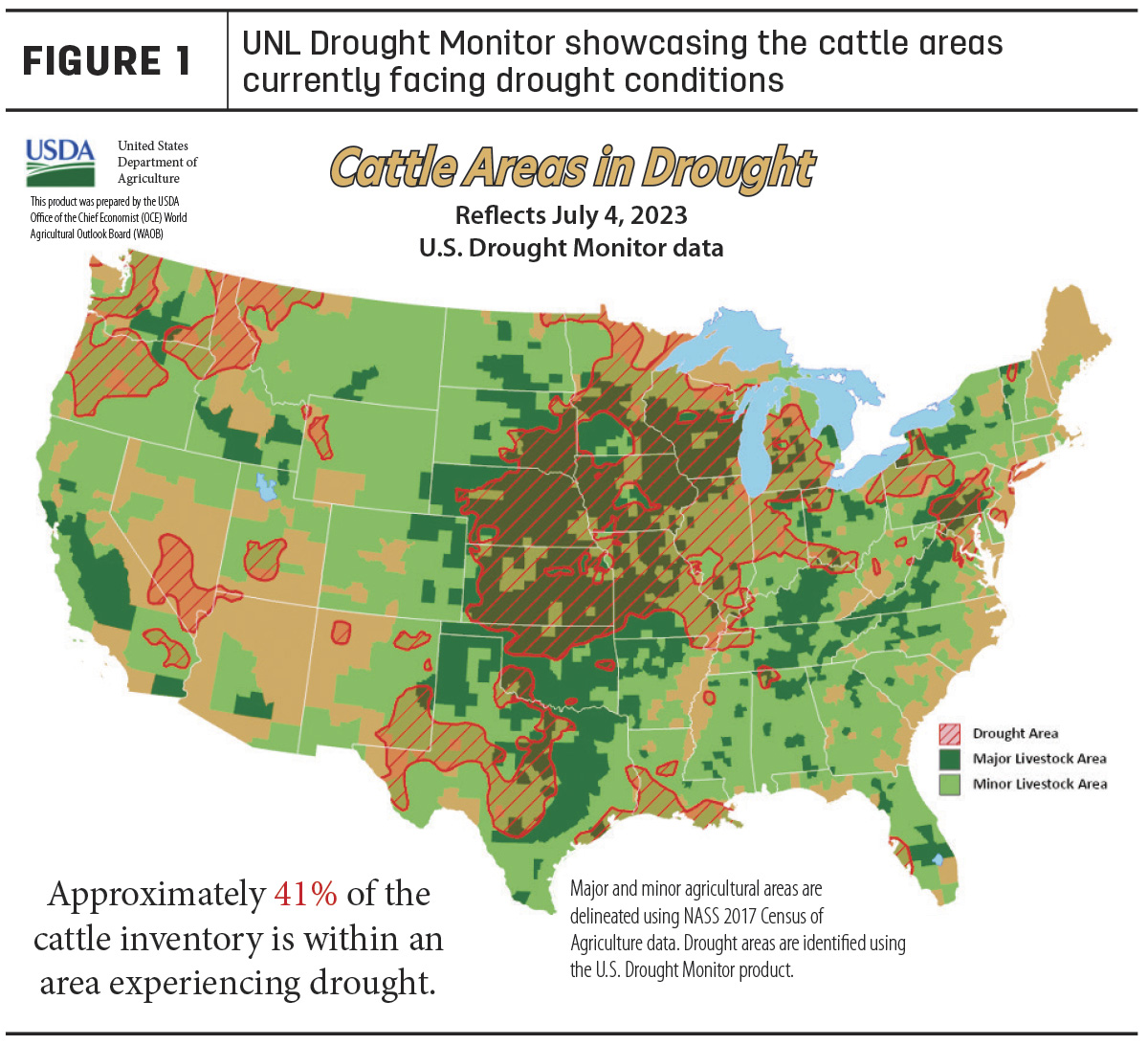

Nutrition in the pregnant cow herd is one area where saving in the short term may not be worth the costs in the long run. With pasture conditions starting out less than ideal in many states, it can be even more tempting to look for corners to cut when it comes to feed costs. Although recent rains may help pasture conditions moving forward, the USDA estimates that many Midwestern states are experiencing greater than 30% of pastures classified as poor or very poor.

Figure 1, courtesy of the University of Nebraska – Lincoln’s National Drought Mitigation Center, showcases the percentage of the U.S. cattle herd experiencing drought conditions. Pasture conditions coupled with tight hay supplies coming out of 2022 and lingering high commodity prices can make the situation seem quite daunting. However, there are still opportunities to optimize feed usage without sacrificing future cow and calf potential.

In the past decade, several studies have demonstrated the importance of maternal nutrition on calf performance. Although we don’t know all the complexities of the role nutrition plays in epigenetics and fetal programming yet, this research has found that nutrient restrictions in pregnancy can have detrimental effects on calf performance. A 2022 meta-analysis found a positive relationship between maternal bodyweight and calf bodyweight, average daily gain (ADG) in the pre-weaning period and weaning weight. This study also reported higher maternal protein and energy intake being associated with higher calf weights. Another study showed supplementation in late gestation led to higher hot carcass weights and marbling scores.

It’s important to note that an oversupply of nutrition during the gestation period may not provide as much benefit as simply providing the required nutrients. Overconditioning late in gestation has been associated with a higher incidence of dystocia and should be avoided if possible. It’s suggested that short-term nutrient restriction may not have as profound an impact on calf performance if the cow’s condition is recovered before calving. When considering the reproductive implications, studies reported that nutrient restriction may lead to more days to return to cyclicity for dams and poorer reproductive performance in heifers. It’s hypothesized that heifers born from nutrient-restricted dams are also less capable of dealing with environmental stressors.

These parameters have a huge impact on the carrying cost of the dam or replacement animal, especially when forage inventory may be limited or bought at a premium and supplement prices are high. If feed costs are around $1.50 to $2 per head, an extra cycle would equate to $30 to $40 added to carrying costs. Although the exact mechanisms have yet to be determined, researchers know that maternal nutrition impacts vary based on calf sex, timing of nutrition restriction, severity of malnutrition and duration of the nutrient restriction.

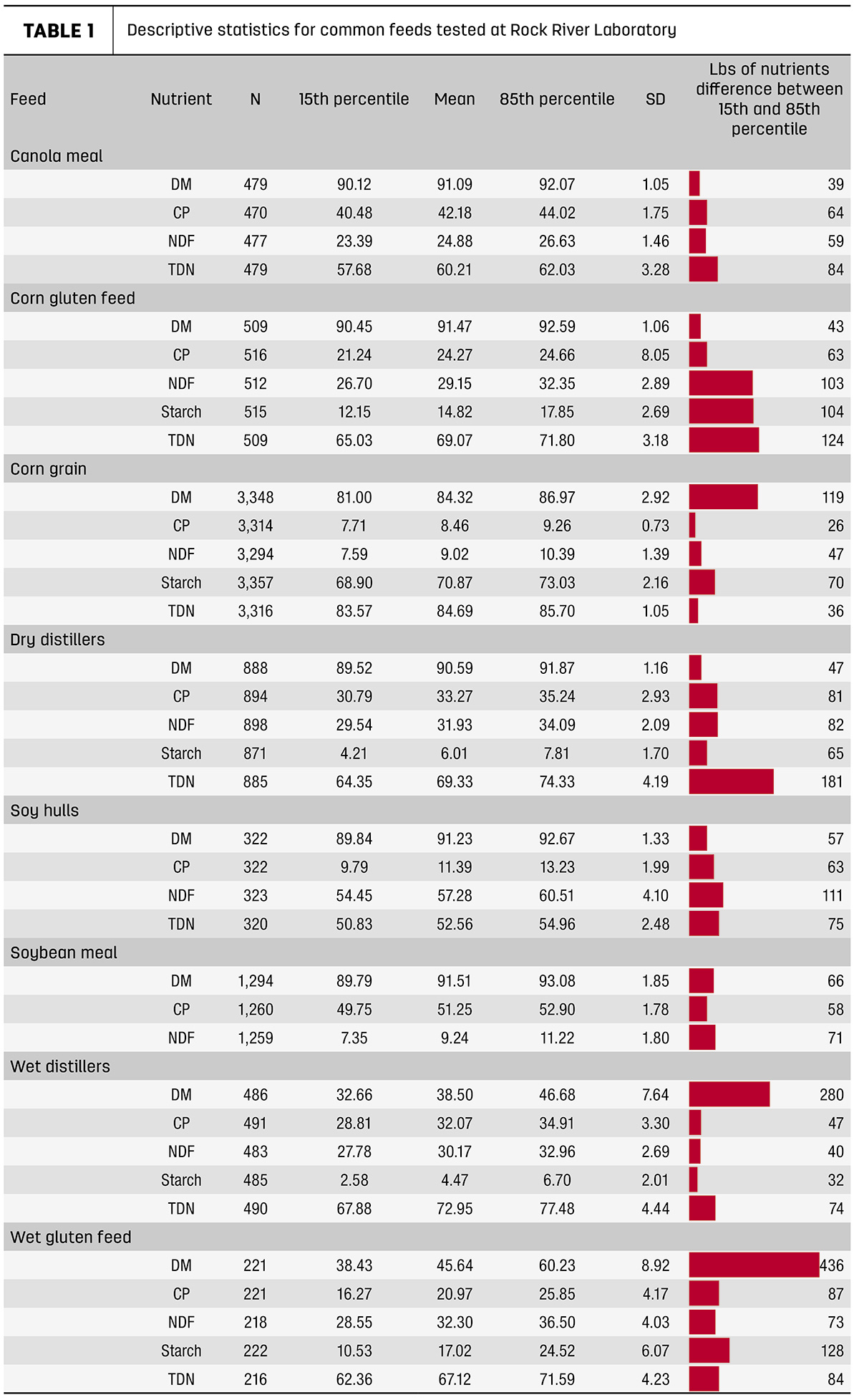

When forage supplies become limiting, byproducts offer a way to decrease feed costs while providing adequate nutrition to both the dam and her developing calf. Although byproducts may be subject to extensive variability, if a quality source can be found, it can be a great way to make ends meet. Also, knowing the true nutrient content of on-hand feed allows producers to supply a more accurate and precise ration, ensuring that expensive nutrients aren’t oversupplied. Even our commodity feeds, which are often considered consistent, are subject to substantial variability. This variability can be a great avenue for producers to capture value on feeds they already have in inventory. Table 1 shows the average and variation in common commodity and byproduct feeds observed and tested at Rock River Laboratory in 2022.

This showcases that the range of nutrients provided per ton of feed can vary widely, which can have major economic impacts. For example, dry distillers with greater than 35.3% crude protein (CP) on a dry matter basis have an additional 80 pounds of CP compared to distillers grain in the 15th percentile. This decreases the cost per unit of protein in this feed by over 4 cents. From a different angle, 80 pounds of CP equates to an additional month of CP per head, assuming CP requirements of around 2 pounds per day. Knowing the nutritional value of a feed can help prevent costly excess nutrient supply.

Often, buyers’ remorse from opting for a cheaper solution can be quickly remedied. However, when thinking about our cow herd, the impacts of suboptimal nutrition in gestation are likely to hang around for many months and can have a large impact on the bottom line. With feeder prices at a five-year high, the difference of 25 pounds of gain in the weaning period equates to around $60 per head. The potential for lighter calves and compromising the reproductive success of the dam and replacement heifers are costly consequences that can be avoided with proper nutrition. In the end, understanding the nutritional value of on-farm feeds can help ensure accuracy and economic impact of rations fed.

References omitted but are available upon request by sending an email to the editor.