Beef cattle producers have a variety of production and management options and technologies from which to choose as they strive to improve the productivity, efficiency and profitability of their operations. To remain competitive in today’s beef industry, commercial producers must identify and implement technologies that have favorable impacts on their beef cattle enterprises, and crossbreeding is one such technology. The two most recognized benefits of crossbreeding are breed complementarity and heterosis.

There is no one breed of beef cattle that is perfect for every environment, production and management situation, and marketing protocol. Breed complementarity is the production of more desirable offspring by crossing genetically different breeds that have complementary characteristics. In other words, breed complementarity is when producers blend the superior traits of one animal with the superior traits of another animal into their crossbred offspring. One example in the southern U.S. is how the environmental adaptability of Brahman cattle has been combined with superior carcass quality characteristics of several other breeds.

Another notable benefit of crossbreeding is heterosis, which is referred to as the superiority in the average performance of crossbred animals compared to the average performance of their straightbred parents. The amount of heterosis for a trait is inversely related to the heritability for a trait. Heritability is the amount of variation in a trait that is due to genetics – in other words, the portion of that trait that can be passed down. Several economically important traits (i.e., reproduction, longevity) have low heritabilities and do not respond to selection as readily as more highly heritable traits (i.e., carcass, growth). The heterosis generated in a crossbreeding system can improve an animal’s performance for lowly heritable traits. The effects of crossbreeding have been shown to be cumulative, and research has shown that overall production may increase 20% to 25% when crossbreeding is used to its full potential.

Industry surveys have shown that 40% to 50% of responding producers characterize their cow herds as crossbred. Given the potential benefits of crossbreeding, it would seem that a greater percentage of commercial cattlemen would implement the technology. However, through the years, several factors have been noted by producers as reasons not to use crossbreeding. One of those factors is the difficulty of evaluating and selecting sires for use in crossbreeding programs.

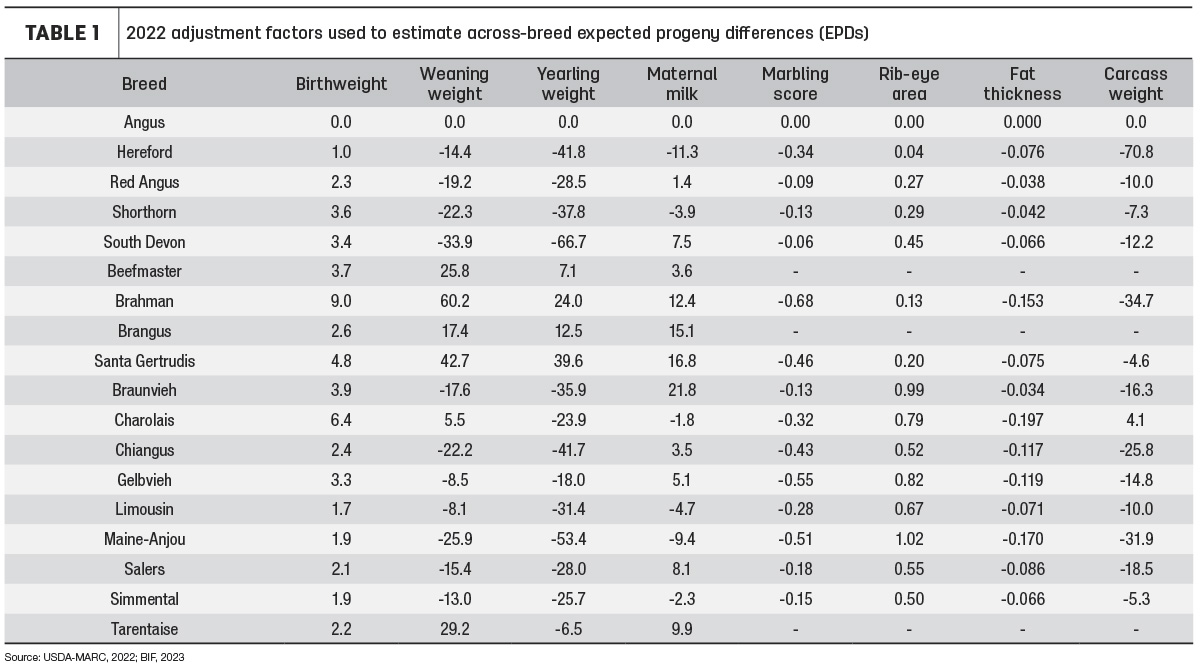

Since the release of the first beef sire summary in the early 1970s, producers have benefited from using expected progeny differences (EPDs) to select animals to meet defined or desired production goals. However, since EPDs are specific to the breed from which they were generated and cannot be compared from one breed to another, commercial beef producers using crossbreeding have found challenges in using EPDs. To address these challenges, the concept of across-breed adjustment factors was employed. For several years, researchers at the UDSA’s Meat Animal Research Center (USMARC) in Clay Center, Nebraska, have evaluated breeds, collected data and developed tables of adjustment factors that account for differences between breeds. These adjustment factors are updated annually and released through the Beef Improvement Federation (BIF). The most recent list of evaluated breeds, associated EPDs and the corresponding across-breed adjustment factors are presented in Table 1. Examples of how to use the adjustment factors to calculate an across-breed EPD follow.

To calculate an across-breed EPD, you need a current trait EPD that has been generated and supplied from a breed association and a current across-breed adjustment factor for the same breed and trait. Consider a Hereford bull with a maternal milk EPD of +25.0 pounds and a Gelbvieh bull with a maternal milk EPD of +25.0 pounds. The across-breed adjustment factors for maternal milk are -11.3 pounds for Hereford and +5.1 pounds for Gelbvieh. To calculate an across-breed maternal milk EPD for the Hereford and Gelbvieh bulls, simply add the adjustment factor to the bulls’ original maternal milk EPD. The resulting across-breed maternal milk EPD for the Hereford bull is 13.7 pounds (25.0 + [-11.3]), and the across-breed maternal milk EPD for the Gelbvieh bull is 30.1 pounds (25.0 + 5.1).

Keep in mind that maternal milk EPD exemplifies the genetic milking ability of a bull’s daughters and is expressed in pounds of weaning weight. The expected difference in milking ability of these bulls’ female progeny, when both bulls are mated to cows of another breed, is about 16 pounds (30.1 - 13.7 = 16.4 pounds). In other words, there is a fair amount of difference in what these bulls can provide in terms of milking potential to their female progeny.

As producers switch between breeds and select bulls for commercial/crossbreeding programs, EPDs for economically important traits are often compared. On the surface (within-breed EPD), these bulls look identical in terms of maternal milk. However, to make a fair and accurate comparison of these bulls, their within-breed EPD must be adjusted. Once the adjustments are made, it is clear the Hereford bull lacks the ability to pass on the same milking potential to his female progeny when compared to the Gelbvieh bull.

Lack of attention in selecting breeds, bulls from the breeds and making necessary adjustments to EPDs can lead to cows that are not effectively matched to their production environment. Consider the scenario presented above. If the Hereford bull is replaced with a Gelbvieh bull with the same within-breed EPD for maternal milk, the resulting female progeny would have greater milking potential. If replacements are saved and incorporated into the herd, they would have greater maintenance requirements due to greater milking ability and may not efficiently fit the production environment.

An additional way to look at the comparison of these two breeds of bulls is to consider a Hereford bull with a maternal milk EPD of +35.0 and a Gelbvieh bull with a maternal milk EPD of +18.0. As mentioned previously and shown in Table 1, the across-breed adjustment factors for maternal milk are -11.3 pounds for Hereford and 5.1 pounds for Gelbvieh. To calculate an across-breed yearling weight EPD for the Hereford and Gelbvieh bulls, simply add the adjustment factor to the bull’s original maternal milk EPD. The resulting across-breed maternal milk EPD for the Hereford bull is 23.7 pounds (35.0 + [-11.3]), and the across-breed maternal milk EPD for the Gelbvieh bull is 23.1 pounds (18.0 + 5.1).

The expected difference in milking ability of these bulls’ female progeny, when both bulls are mated to cows of another breed, is small (23.7 - 23.1 = 0.6 pound). In other words, these two bulls would provide very similar levels of milking potential to their female progeny. These calculations suggest that if a producer is currently using a Hereford bull with a maternal milk EPD of +35.0 in his crossbreeding program and wants to switch to a Gelbvieh bull, he would need to find a Gelbvieh bull with a yearling weight EPD of +18.0 to maintain the same level of milking ability genetics in the females in his herd.

For more than 50 years, beef producers have had the opportunity to use EPDs, evaluate animals’ genetic potential for a variety of traits and select animals to meet defined or desired production and marketing goals. Today, producers still face challenges as they seek to identify the best sires to use or rotate in commercial/crossbreeding programs. Adjustment factors and the resulting across-breed EPDs can assist producers as they seek to select sires to improve or optimize economically important traits in their herds. The adjustments and comparisons can also help producers keep their cows matched to the environment in which they are expected to perform.