Calfhood diarrhea prevention and treatment is one of the areas of veterinary medicine I’m most passionate about – probably because young calves are incredibly resilient. Simply providing supportive care in these cases typically results in a quick recovery, making them extremely rewarding to treat. There are a few things you as a producer can do to help increase the odds that your calves will overcome this deadly and all-too-common health challenge.

One way to avoid the cost of IV fluids and hospitalization is to identify sick calves early on in the disease process when oral electrolytes may be sufficient to get them on the path to recovery.

Keep in mind that not all oral electrolytes are created equal. Make sure your electrolyte contains an alkalinizing agent in the form of bicarbonate or acetate. I like products that contain acetate; they help calves rebound a little more quickly, in my opinion. Read your bag closely and mix them appropriately. They also need to be on a nutritional supplement and have access to sodium to help get that calf over the hump. Recent research supports the idea of starting to refeed these calves as soon as they will take a bottle or show interest in nursing the cow. Withholding nutrition makes it hard for the calf to maintain its blood glucose levels and may prolong its recovery.

How dehydrated are they?

Is an oral electrolyte going to be a good option, or will you need to go the IV fluid route right away to save this calf? Assessing the calf’s degree of dehydration is important to answer this question.

To estimate their level of dehydration, do so by performing:

Eyeball recession test

This is my favorite way to estimate hydration. It shows how much of a gap there is between their bottom eyelid and the actual eyeball itself. They should be touching when they're normally hydrated, but when they become really dehydrated, that's when you see that eyeball basically start to become more sunken in the orbit and pulled away from that eyelid. To give you an idea, 4 to 6 millimeters of depth between the eyelid and the eyeball correlates to 8% to 10% dehydration.

Neck skin tent

If it takes six to seven seconds for that tent to go all the way back down, that's another indication of around 8% to 10% dehydration. To overcome dehydration that severe, you will likely need to put them on IV fluids.

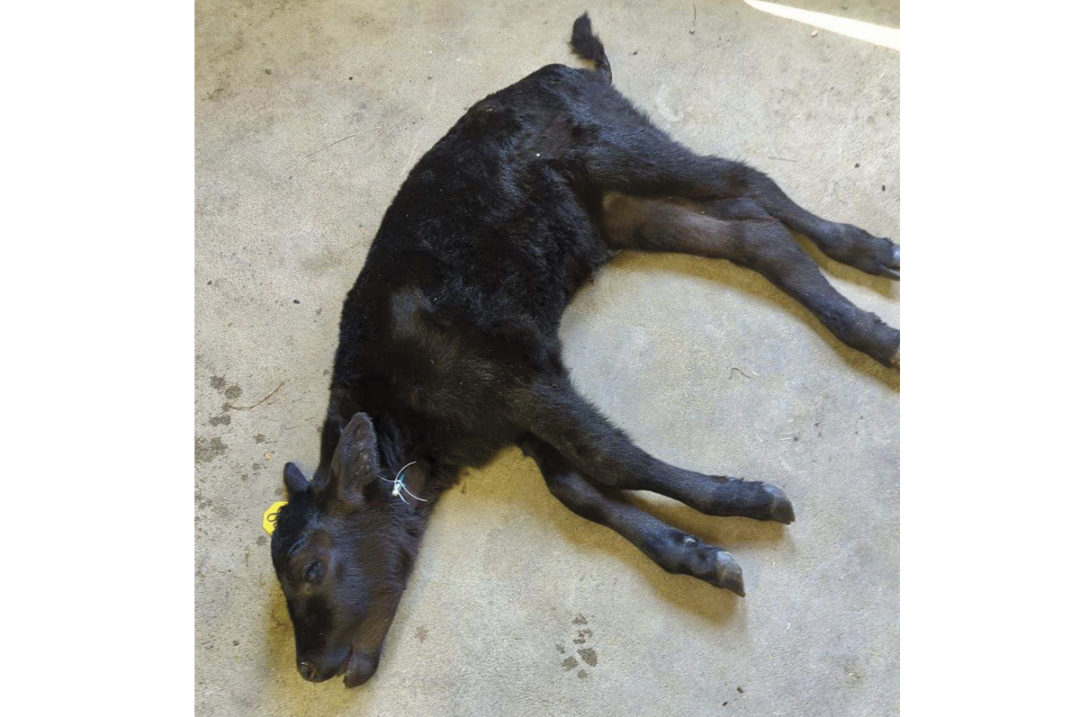

If left too late, IV fluids may be the only possible treatment. Photo provided by Lacey Fahrmeier.

Are they acidotic?

Another important area to assess is how acidotic they are. It’s not just that they're running out of fluids to support their cardiovascular system – they are also becoming what we call acidotic. This means that their electrolytes are becoming so imbalanced, or their damaged tissue is producing so much lactate, that the blood pH is going in the wrong direction. When severely acidotic, they can decline rapidly if proper electrolytes and fluid levels aren’t supplemented quickly.

Here are three easy ways to assess their level of acidosis:

Mentation/attitude

Are they still alert, or are they just totally out of it, eyes glazed over? If they are not mentally appropriate, that is an indicator that their level of acidosis and its effects on the brain are reaching a serious level.

Suckle reflex

When you put your finger in their mouths, do they still have at least a weak suckle reflex? If so, that's a good sign. If they don't have a suckle reflex at all or their mouth is cold, they are typically going to need some IV fluids containing bicarbonate to correct the imbalances.

Posture

If they are able to stand but they're weak and uncoordinated in their hind end, that's an indication that oral electrolytes may still be able to pull them out of it. If they are able to hold their head up while sitting sternal but are unable to stand, you can try oral electrolytes first, but if they don't show significant improvement within a few hours, IV fluid therapy may be needed. If they're laid out flat, IV fluids are your only treatment option, and time is of the essence. Get them to a veterinarian that can place an IV catheter and start fluids immediately.

Looking at these key indicators will help determine which treatment approach needs to be taken to ensure the most successful outcome for the calf.

Are they showing signs of septicemia?

Septicemia means bacteria are circulating in the bloodstream and multiple organ systems are under attack by the infection. Some diarrhea calves may be having issues that affect more than the gastrointestinal tract. If they have a high fever, enlarged joints, an enlarged or painful umbilicus or are exhibiting neurologic signs, they may be battling septicemia.

Scleral injection – or when blood vessels in the eye are engorged and red – is a key indicator of septicemia. Photo provided by Lacey Fahrmeier.

When performing my initial exam on a sick calf, one of the best indicators to help determine if the calf is septic, in addition to being dehydrated, is to lift their upper eyelid; look at the white part above their iris (the sclera) and check to see if the vessels located in that area are engorged and angry. When a calf has an infection and is septic, those vessels become visible and engorged – we call this scleral injection. When the calf is healthy, you really shouldn't even be able to see those vessels.

If the calf has a fever, obvious scleral injection, is lethargic or has an enlarged navel or joints, those are some strong clinical signs that there is an infectious process taking place, and antibiotics are indicated for treatment. If the causative agent for disease is viral, such as rotavirus and coronavirus, you may just need IV fluid support, and antibiotics would not be needed. If there is blood in the manure, that can be an indication of an E. coli infection. We typically see E. coli in younger calves (less than 10 days old), and you will need antibiotics in order to help that calf recover.

Prevention

With record-setting calf prices this year, vaccines can prove to be cheap insurance for protecting your investment. If you've dealt with a scours issue in the past on your operation and you know what you're up against – such as rotavirus, coronavirus or E. coli – effective vaccines are available that you can use either in the pregnant dam to boost colostral antibodies or give orally to the calf at birth. Timing of pre-calving cow vaccination is critical to colostrum formation and quality of calf scours protection. The final scour vaccine should be given three to six weeks before calving. For the calf, I recommend giving an oral scour vaccine, an injectable clostridium vaccine that contains perfringens type C and D, and an intranasal respiratory vaccine within the first eight hours following birth. That can be challenging if you aren’t able to check the calving cows often or labor is limited. Every herd has different risk factors for disease; working closely with your veterinarian to determine the best vaccination protocol for your herd is well worth the time and money.

Additionally, drastically reduce the incidence of scours by following the Sandhills Calving System.

Dealing with a scours outbreak is mentally and financially draining, but with the right prevention strategy and treatment plan, you can help reduce risks.