Profitable dairy production requires a very efficient conversion of feed to milk. A combination of purchased and home-raised feeds are frequently used to provide the needs of the dairy operation.

Many Northeast dairy producers have increased the use of double-cropped forages on their corn silage acreage to produce small-grain silages to replace alfalfa haylage in their rations. Removing perennial forages from their rotation has allowed them to increase the acreage available to produce corn grain. In many states, farms can grow corn grain for far less than the market price of the commodity.

One of the first strategies to consider is: How well do the cow numbers fit the crop acreage? When cropland acres are a poor match to cow numbers, the cost of purchased corn and a shortfall of hay crop forages pushes up the cost of purchased feed for the farm. If land available to rent is in short supply, using a double-cropping strategy can significantly increase the tons of forage a farm can produce on the same acreage.

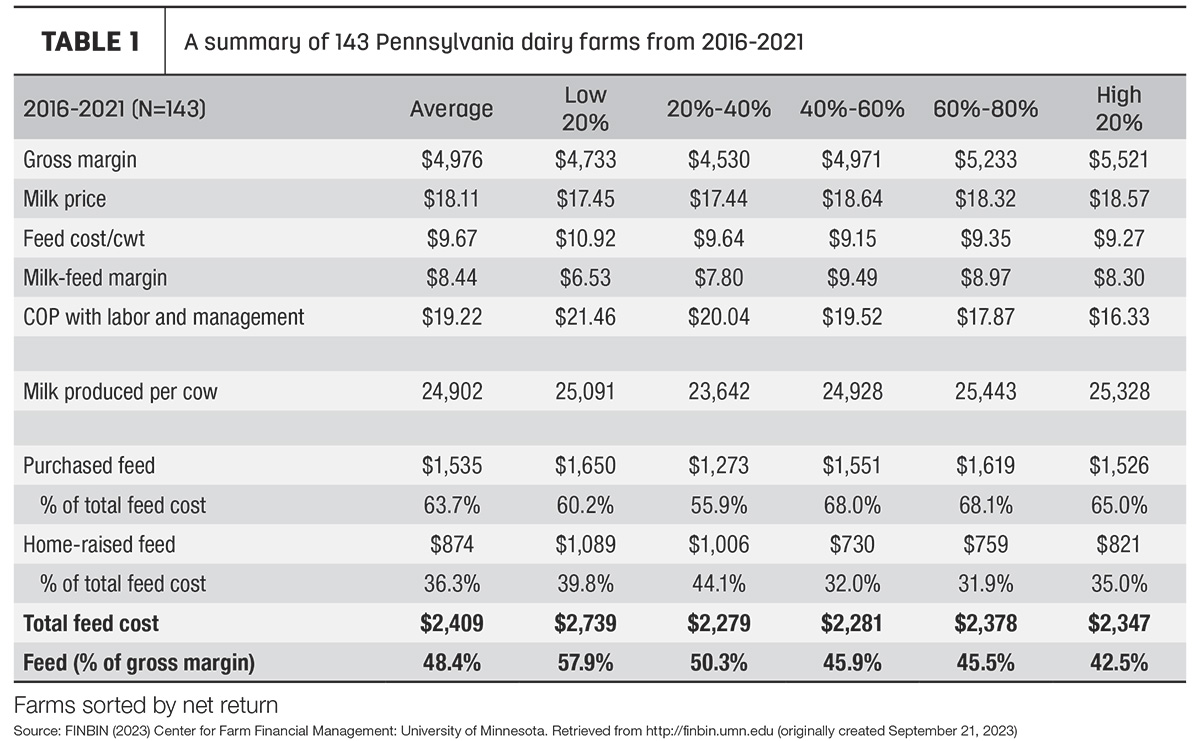

Table 1 summarizes 143 Pennsylvania dairy farms from 2016-21. The farms are sorted by net return into five profitability groups. Total feed cost listed in the table refers to the cost of both purchased and home-raised feeds for all animal groups on the farm including milking cows, dry cows and heifers. In the six-year data summary, total feed cost averaged $2,409 per cow per year. It is important to note the four highest profitability groups were below this average. The least profitable group spent $2,739 per cow per year for total feed cost.

Looking at the split between purchased and home-raised feeds shows home-raised feeds were a lower percentage of total feed cost (31.9 – 35%) in the three highest-profit groups. The two low-profit groups spent 39.8% and 44.1% of total feed cost on the cost of home-raised feeds. This suggests these low-profit farms used very similar crop input costs but experienced lower crop yields. These farms also likely had forage quality issues because the low-profit group had both the highest cost of purchased feed and the highest home-raised feed cost. Trying to buy back nutrients to make up for poor forage quality seldom results in a profitable dairy.

Perhaps the most important item shown in this data is the importance of the milk-feed margin to the profitability of the farm. This margin is calculated by taking the milk price and subtracting off the cost of feed on a hundredweight basis. Across the multiple-year data, the margin averaged $8.44 per hundredweight (cwt), with a range from $6.53 to $9.49 per cwt. This measure is useful because it gauges the value of the farm output to the input costs used to make the product.

The bottom line of the table shows how much of the farm’s gross margin was required to supply feed for the dairy. This measure clearly shows a wide range of efficiency in converting feed to milk. The high-profit group used 42.5% of their gross margin to pay for feed, while the low-profit farms spent 57.9% of the gross margin on feed. This fits well within our historical observation that cost of feed can range from 40% to 60% of milk income. The percentage required for feed stair steps up as profitability declines.

Photo courtesy of Penn State Extension.

While this data shows the importance of total feed cost to the profitability of the dairy farm, the larger lesson is how well the farm converts feed to milk for the dollars invested to produce it. Dairies can benefit from double-cropping strategies that produce more home-raised feed, but crops must be well managed to provide high yield with managed input costs and high-quality forage that will support high milk yield. Identifying ways to manage this feed conversion process will surely produce more profit for the dairy operation.