In the ’50s and ’60s, alfalfa was grown on hundreds of thousands of acres across the South. However, alfalfa acreage has waned in the decades since. Producers had cheap nitrogen (N) fertilizer to grow grass and cheap grain to feed if higher-quality feed was needed.

When compared to bermudagrass or the other grass forage crops, alfalfa was needy and expensive. Insecticides to control alfalfa weevil were still new and expensive, and persistence problems became more chronic.

The plant breeders started to favor varieties for the Northern and Western states where soil fertility and disease issues are less challenging relative to the South. Consequently, a whole generation of forage producers grew up thinking alfalfa just wouldn’t grow in the South.

Times have changed. By comparison, N prices have jumped through the ceiling, forage quality has never been more important, and insect controls are much less limiting.

Most importantly, plant breeders have begun to realize the great potential for the alfalfa market in the South. But should it be grown here?

There are many practical and economic reasons why alfalfa should be more extensively grown in the South. First, it allows producers to grow their own nitrogen. Alfalfa produces between 250 and 400 pounds of N per acre per year.

At current prices, that N is worth more than $180 per acre. Alfalfa also produces forage that is far superior to the South’s currently dominant hay crop of bermudagrass.

The superior quality of alfalfa is often more than many livestock classes need. Consequently, researchers in Georgia and South Carolina began experimenting with interseeding alfalfa into bermudagrass.

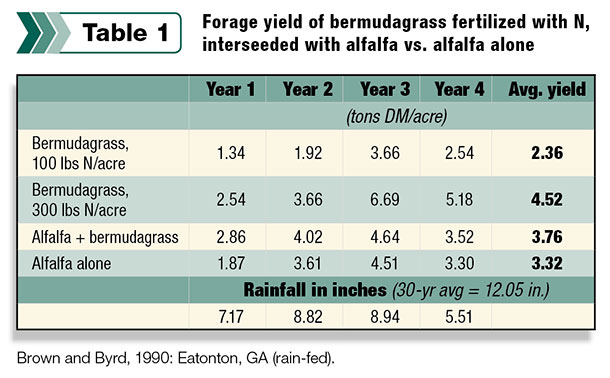

Their early research showed that alfalfa could be successfully grown with bermudagrass (Table 1).

Alfalfa-bermudagrass hayfields produced yields comparable to bermudagrass fertilized with 200 to 300 pounds of N per acre per year.

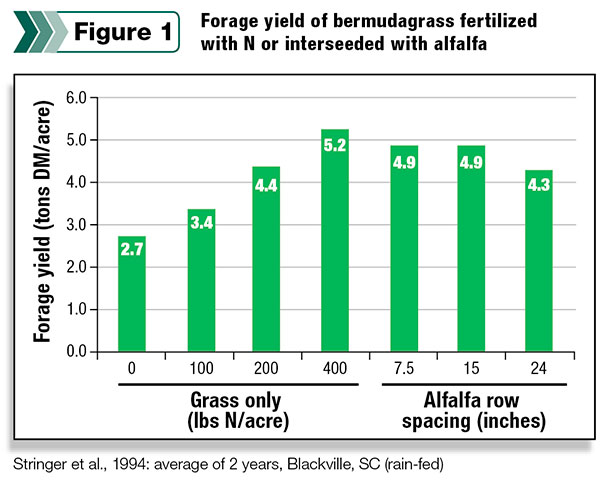

Subsequent work in South Carolina showed this remained true even when the alfalfa was planted in 15-inch rows (Figure 1).

When grown on 15-inch rows, the forage contained an average of about 80 percent alfalfa and 20 percent bermudagrass during the first four years of production.

This balance of alfalfa and bermudagrass results in forage that is 30 to 40 relative feed quality (RFQ) points higher than bermudagrass alone. This increased quality reduces or eliminates the need for buying supplemental energy or protein.

In fact, some of the spring and late-fall forage is often in excess of 200 RFQ. Producers who have made the switch brag that they have started growing their own supplement, in the form of high-quality alfalfa.

Additionally, many producers have started baling and selling small square bales during the summer to sell as a valuable cash hay crop.

Growing alfalfa with bermudagrass also has many practical benefits. Drying alfalfa in the South has historically been challenging. However, modern mower-conditioners and tedding equipment can increase the drying rate by 50 to 60 percent.

Additionally, growing alfalfa with bermudagrass allows the alfalfa to dry faster and be harvested more cleanly. When alfalfa is grown with grass, the cut sward seems to create an architecture that allows for faster drying.

Plus, alfalfa retains more leaves when grown with bermudagrass and has less ash content, since the grass sod minimizes soil contamination.

Growing alfalfa with bermudagrass also has built-in risk management. If all else fails, one still has bermudagrass. In fact, a field that seems to have poor uniformity with regard to its alfalfa distribution is not overly problematic.

The alfalfa will eventually play out. The bermudagrass remains and reclaims its dominance, usually after four or more years. Areas where the alfalfa is thin will serve as a beachhead from which the bermudagrass will reinvade.

There are certainly some places where alfalfa is not a good fit. The following are five situations where it is common that alfalfa cannot be successfully established:

- The site is poorly or even moderately drained. Alfalfa needs a well-drained soil and does best when it has an opportunity to send its taproot deep into the soil profile. Alfalfa does not persist well in wet soil because its roots cannot maintain proper function in saturated conditions.

- The site has a soil pH that is too low. The soil pH needs to be equal to or greater than 6.5. Moreover, alfalfa requires the subsoil pH (8- to 24-inch depth) to be above a pH of 5.5.

This is because even minute levels of soluble aluminum in the soil solution hinder alfalfa root development. Aluminum solubility is a major problem in subsoil that has a low pH. This is more challenging in the highly weathered soils in the southern U.S.

- The soil is low in phosphorus (P) or potassium (K) fertility. Alfalfa requires a significant amount of P and K. If either is low (according to one’s university soil test results), this can result in poor establishment or extraordinarily expensive fertilization.

- The soil is too sandy. The southern U.S. has many locations that have very sandy soil types. There is no definitive guide to what is “too sandy,” but one should avoid sites where the soil type is classified as “sand” and has less than 1 percent soil organic matter.

Sandy loam soil types, which are the most prominent type in the Southern Coastal Plain, are quite capable of producing alfalfa.

- Herbicide residues are present. Many grass pastures and hayfields will be treated for weeds. Many of these herbicides remain active in the soil and can damage alfalfa seedlings for months after application.

Read the herbicide labels for guidance on when alfalfa can be planted after an application or avoid using residual herbicides.

Growing alfalfa in the South is no longer a pipe dream; it is a reality. In research plots and on-farm comparisons, forage researchers from Virginia to Texas (and every state in between) have conclusively shown that interseeding alfalfa into bermudagrass can be quite successful.

Convinced? Then follow these key steps to successful establishment of alfalfa in bermudagrass:

1. Select an appropriate site for planting, ensuring that the site is well drained, has been managed for an optimum pH (pH of the topsoil consistently greater than 6.3 and subsoil pH greater than 5.5), is moderate to highly fertile in P and K, is not too sandy and has no herbicide residues present that may hamper establishment.

2. Test soil at the site; apply lime to ensure a pH of 6.5 or greater at the time of planting, and fertilize according to recommendations, including with micronutrients (boron and molybdenum) if needed.

3. Plant at the right time of the year (consult your state’s extension recommendations).

4. Clip or graze the bermudagrass very short (1 to 2 inches) prior to planting.

5. Spray the field with a light rate of a non-selective herbicide to “chemically frost” the bermudagrass, preventing it from growing back and competing with the seedling alfalfa.

6. Plant with a no-till drill at a seeding rate of 22 to 25 pounds per acre if planting into 7- to 9-inch rows or 11 to 13 pounds per acre if planting into 15-inch rows, and ensure seeds are planted a quarter- to half-inch deep.

7. After the alfalfa emerges, spray with an inexpensive insecticide (such as one of the synthetic pyrethroids) to control insect pests.

8. Irrigate if available and necessary. FG

-

Dennis Hancock

- Associate Professor and State Forage Extension Specialist

- University of Georgia

- Email Dennis Hancock