Many areas of the Corn Belt experienced late-season rains. In some of these same areas, the ear did not drop and, consequently, the ear developed fungal growth. Mold growth itself is not detrimental to livestock, but the mycotoxins produced by the mold can cause problems.

Not all molds produce mycotoxins, and some molds produce more than one mycotoxin, and those mycotoxins can interact to cause further problems. This article will focus specifically on beef cattle, but other species such as hogs, poultry and even dairy cattle are significantly more susceptible to mycotoxin effects.

It appears that this year fusarium is problematic and predominates among molds in corn. This is likely because of the late-season moisture in the northern reaches of the U.S. and subsequent ear rot and head blight. Fusarium molds produce the toxins fumonisin, fusaric acid, deoxynivalenol (DON), zearalenone and T-2.

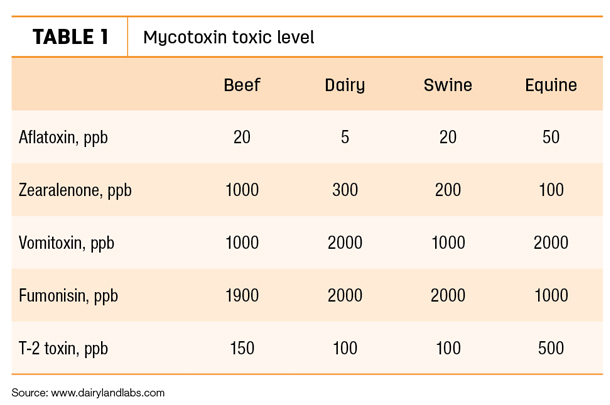

Mycotoxin analyses this fall have revealed the presence of these mycotoxins in the upper Midwest, which have resulted in production problems. Table 1 gives basic recommendations for levels of mycotoxins which should cause concern for producers.

Even though mycotoxins are detrimental, they are also one of the most over-diagnosed maladies in the feedlot. It is true that young, newly received feedlot cattle are extremely sensitive to mycotoxin contamination.

Even though mycotoxins are detrimental, they are also one of the most over-diagnosed maladies in the feedlot. It is true that young, newly received feedlot cattle are extremely sensitive to mycotoxin contamination.

As a group, mycotoxins work in concert to dramatically reduce immune function and, as such, predispose otherwise healthy feedlot calves to illness.

T-2 toxin specifically reduces the body’s innate ability to fight infection and mount a vaccination response. Most mycotoxins also reduce feed intake, which is always a struggle in newly received feedlot cattle.

However, as stark as these effects may be, these symptoms are also caused by any number of other maladies or chemicals. Be certain that you, your nutritionist and veterinarian explore all options when presented with a group of chronic calves to determine the correct diagnosis.

In general terms, feedlot cattle up on feed are less susceptible to mycotoxin effects than many other classes of livestock but can still be impacted by highly concentrated feedstuffs. One mycotoxin of particular concern in feedlots and in breeding cattle is zearalenone.

Zearalenone is similar in structure to estrogen and can elicit many of the same responses as endogenous estrogens. Estrogenic mycotoxins such as zearalenone will cause swollen udders and vulvas, and may cause expression of sexual behavior in cattle, such as riding.

It is prudent to consider zearalenone contamination if you have an implanted pen of feedlot cattle riding incessantly. Perhaps it is not the result of inappropriate implant technique or timing but rather a combined onslaught of estrogens from mycotoxins and implants.

Breeding cattle are similarly susceptible to mycotoxins, and zearalenone has a proven history of causing abortions and secondary sex characteristics in young heifers.

Many mycotoxin tests will reveal the presence of DON. However, in most cases DON is not detrimental to cattle by itself. However, the presence of DON indicates fusarium contamination, and with fusarium comes the other mycotoxins listed earlier such as fusaric acid, fumonisin, T-2 and zearalenone.

These mycotoxins, unlike DON, are often detrimental and will cause production problems. Moreover, many mycotoxins, when administered by themselves, are not damaging – but when found in feedstuffs, they create toxic effects. This is likely because the mycotoxins are working in concert.

DON, for example, does not typically cause vomiting in swine by itself but, when combined with fusaric acid, causes vomiting – hence the alternative name vomitoxin.

In the case of beef cattle, we have the luxury of options to feed our livestock. Unlike our counterparts in the swine and poultry business, corn does not need to comprise the majority of rations in growing and finishing cattle, nor does it in breeding cattle.

However, distillers grain, which is an excellent replacement for corn, can be very high in mycotoxins.

The process of ethanol production will as much as triple the concentration of some mycotoxins in the final feed byproducts. Corn gluten feed, on the other hand, is quite safe. Since corn gluten is a byproduct of the sweetener (among other ingredients) industry, the corn is held to a higher standard for contamination and, as such, is generally very low in mycotoxins.

Corn chopped for silage, earlage or snaplage can also contain significant mycotoxin contamination. The fermentation process does stop active mold growth but does little to reduce mycotoxin contamination.

Inappropriate storage of high-moisture feeds can be another source of mold growth. It is absolutely critical to harvest, pack and cover high-moisture feeds as well as apply an inoculant or preservative to ensure adequate fermentation to eliminate oxygen and subsequent mold growth.

Once a feedstuff is contaminated by mycotoxins, the solution is very simple: dilution. However, in cases where multiple feeds are contaminated, or where the concentration of mycotoxin is quite high, one must consider a mycotoxin binder. The business of selling mycotoxin binders is competitive and lucrative.

Consequently, there are many choices in products and suppliers. I will not try to suggest a single binder product but rather encourage you as the producer to work with a supplier to select the right binder for your particular mycotoxin and delivery method.

Many binders have quite low inclusion rates and are difficult to mix adequately unless pre-blended by a feed mill. Good binders can also be quite expensive, ranging from 5 cents to 15 cents per head per day. However, this cost is small in comparison to performance losses or mortality because of mycotoxin contamination.

Mycotoxins are present every production year. However, wet falls such as this past one make feedstuffs more prone to mold and subsequent mycotoxin contamination.

Research has clearly proven that certain mycotoxins, in sufficient quantity, can cause problems including performance losses, reduced feed intake and substantial reductions in immune function and reproductive losses in cattle.

Testing is key to reducing the impact of mycotoxins. However, testing is not foolproof, and often it is necessary to make a judgement call in the face of problems, even though the test may not reveal a significant mycotoxin problem.

Work closely with an advisory team including nutritionists and veterinarians to develop the right mycotoxin management program for your operation. ![]()

PHOTO: Late-season rains contributed to a rise in silage mycotoxin levels. While feedlot cattle are less susceptible to mycotoxin effects than other classes of livestock, highly concentrated feedstuffs can still be problematic. Photo courtesy of Rock River Labs.

-

Dan Larson

- Great Plains Livestock

- Consulting Eagle, Nebraska

- Email Dan Larson