Texas A&M AgriLife Extension regularly hosts a two-day conference in late May/early June for beef producers interested in direct-market beef sales. The event, formerly known as the Grass-Fed Beef Conference, was rebranded as the Ranch-Raised Beef Conference in 2023 to include producers who finish cattle on either grain or grass and market beef directly from their ranches. Marketing beef directly off the ranch often means direct conversation with customers. Naturally, the conference rebrand sparked discussion on how to discuss beef sustainability with individual buyers.

“Sustainability” is undoubtedly a buzzword, and buzzwords elicit passionate opinions. If you ask 100 people on the streets of downtown Austin, Chicago or Los Angeles to define sustainability, their definitions will likely focus heavily on the topics of climate change, alternative energies and the moral dilemma of consuming meat – i.e., environmentally driven responses. Conversely, if you query the halls of the exposition center at CattleCon, the bustling roads of the Farm Progress Show or the tie-out pens at the county fair, folks’ definitions will be highly considerate about the futures of their operations.

This is certainly not to say that cattle producers believe environmental stewardship is not crucial to maintaining the future of their operations, nor is it to generalize so-called “city folks” as a mindless mass who want livestock producers to lose their businesses at the expense of maintaining a threatened species. Such is the dilemma of the word sustainability. It is a multifaceted, emotionally charged and oftentimes controversial topic. In fact, researchers at the Colorado State University (CSU) AgNext Center borrow the term “wicked problem” from socioeconomic policy to describe sustainability: a concept that has no singular solution due to the infinite trade-offs, worldviews and stakeholders involved.

Our society inadvertently rewards tunnel-visioned, us-versus-them and black-and-white thinking for a myriad of topics. Animal agriculture suffers continuously from the blowback of these types of mindsets. For example, popular media often portrays grass-fed beef as natural and idyllic, and paints grain-finished cattle as unnatural and environmentally problematic. On the flip side, some sectors of the agricultural industry internally portray grass-finished beef as a less efficient, niche product marketed to uninformed and/or self-righteous customers. Undeniably, many of us who work in the cattle industry are also guilty of a one-track mind as to what is efficient or sustainable. The truth is that the pursuit of sustainable balance requires inevitable, and sometimes immeasurable, cascading trade-offs.

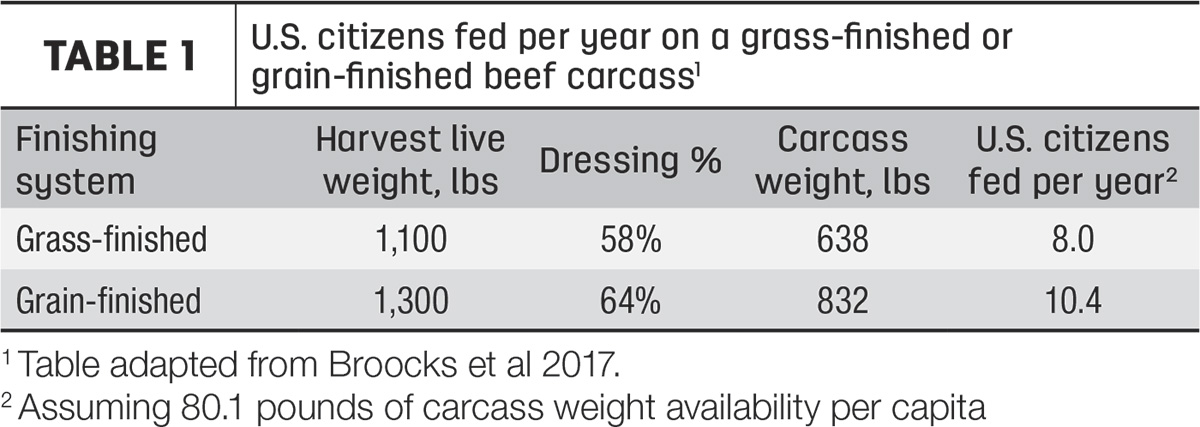

If we want to conduct a fair inquiry on the sustainability of beef operations, we must move away from a “versus” mentality toward an “and” mentality. A versus mentality begets generalizations that rank one type of feeding system over another, i.e., statements such as, “grain-finished cattle are more feed efficient and therefore more sustainable than grass-finished cattle.” One may draw this conclusion from Table 1, which demonstrates that the average grain-finished beef carcass will yield a greater hot carcass weight in the same number of days on feed relative to its grass-finished counterpart.

It is true that concentrate-fed cattle will reach an acceptable market weight more quickly than those only fed forage. However, concluding that feed efficiency is the sole key to more-sustainable beef operations naïvely proposes a blanket solution to maintaining economic efficiency for any operation. Most rational people would argue that there are seen and unseen nuances in the cattle-raising business that prohibit sweeping generalizations.

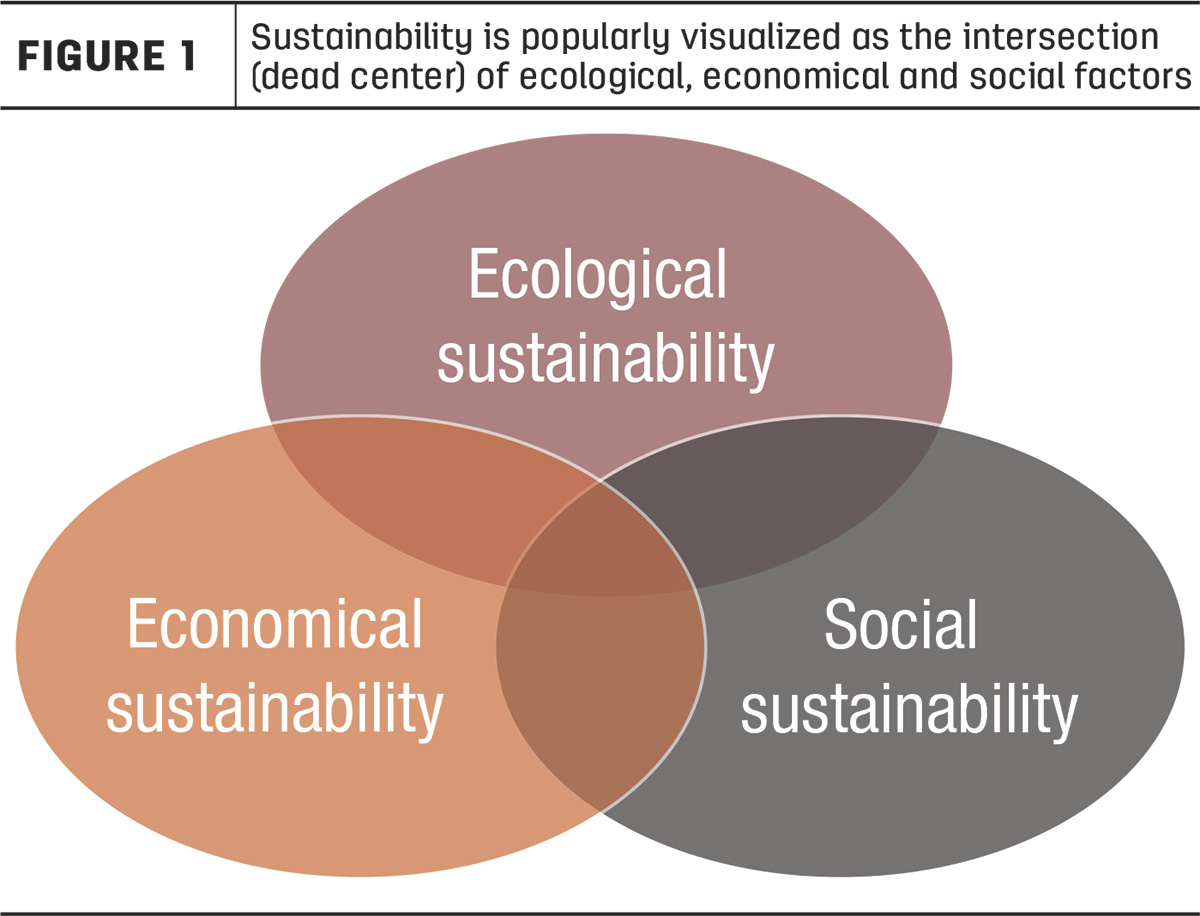

Rather than pitting producers against one another, we can discuss a more encompassing truth: Both grain-finished and grass-finished operations are sustainable, and there are opportunities for adopters of both systems to ensure the futures of their operations through environmental, economic and social means. In fact, sustainability is popularly conceptualized through a three-way Venn diagram, in which the three intersecting ovals represent environmental (or ecological), economical and social sustainability (Figure 1).

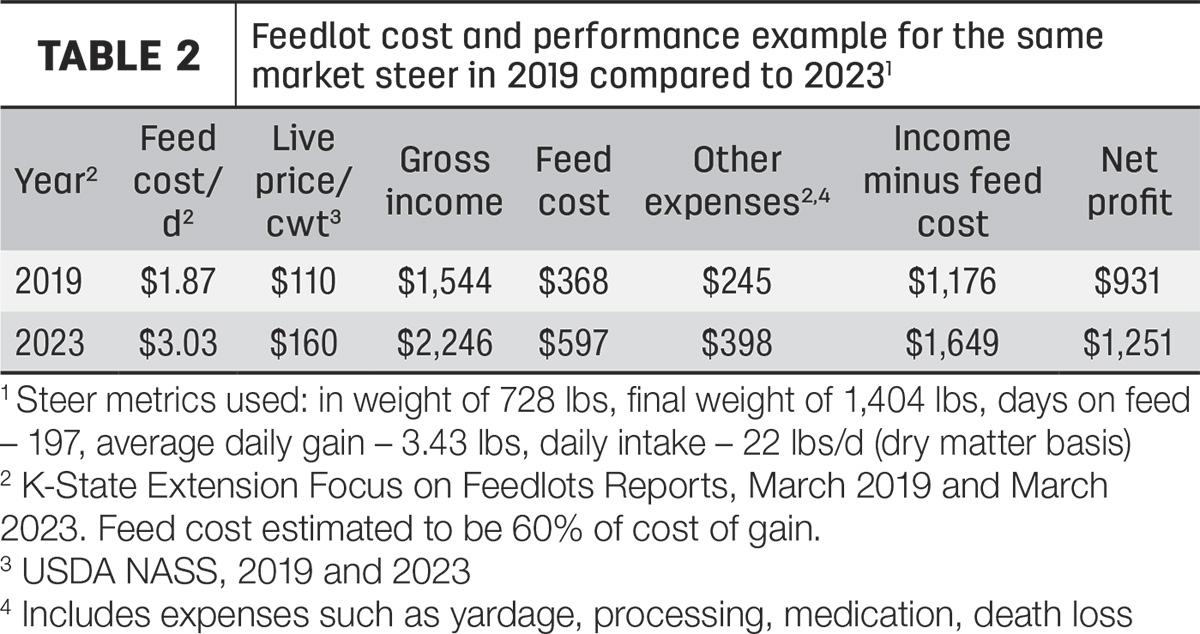

The dead center overlap of the three concepts would represent utopian-level sustainability of a particular operation. Arrival at dead center is not possible. The volatile and uncontrollable moving parts of societal norms, politics, cattle and grain markets, etc., prohibit that. If a producer raised a steer with the same feed efficiency in both 2019 and 2023, factors outside of management, genetics and nutrition had radical effects on their bottom line (Table 2).

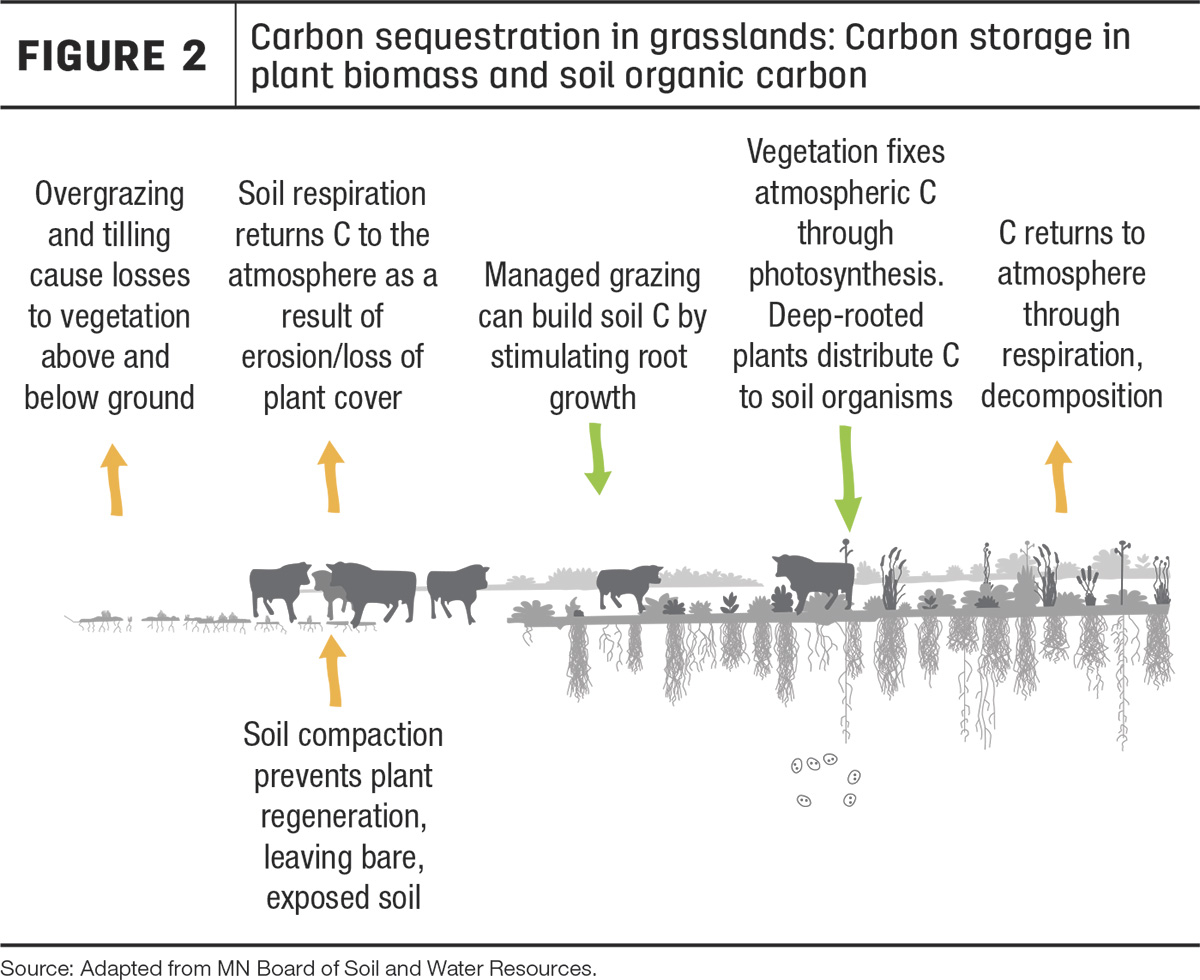

In terms of the carbon footprint comparison between the two systems, the jury is still out. The methods by which carbon emissions are measured are still argued – just refer to Frank Mitloehner’s June 2023 piece in Progressive Cattle on global warming potential metrics. Still, the Beef Checkoff predicts an 18.5% to 67.5% reduction in carbon emissions of grain-fed compared to grass-fed beef – nearly a 50% variation from operation to operation. High-fiber diets promote activity of methane-producing organisms in the rumen, which is why grass-finished beef is associated with greater methane release into the atmosphere. However, to quote Sara Place, an associate professor at CSU, methane production is a sign of life. Cattle evolved to host those microorganisms in their guts so that they could digest highly fibrous food that humans cannot consume. Further, grass-finished animals sequester carbon into the soil in ways that grain-finished cattle don’t (see Figure 2).

The methane trade-off is that grass-finished animals can convert more human-inedible plants into lean protein than concentrate-finished animals. And although grain-finished animals are undeniably more feed-efficient than their forage-finished counterparts, grass-fed beef producers can opt into value-added programs and sustainability-related revenue options such as governmental subsidies, carbon and biodiversity markets, certifications for low-carbon beef and carbon insets.

In sustainability, there is no clear solution; there is only improvement, maintenance or regression. Thus, we must emphasize to rational consumers that nirvana is not a realistic or attainable goal for any business. Both the people who do and don’t play a role in raising the food we eat are flawed, complex and generally well-intentioned. The underlying motivator is the same for folks who finish cattle on grass and grain: The world needs and wants high-quality animal protein, and progressive farmers and ranchers who make decisions based in science and intuition will provide it.