We all know how important it is to optimize resting behavior for lactating dairy cows.

Failure to permit cows to rest when they want to, for as long as they need to, has a negative impact on their ability to produce milk, become pregnant, stay healthy and remain in the herd.

Lying behavior is influenced by the design of the resting space, climate, stocking density and the time made available for rest while in the home pen.

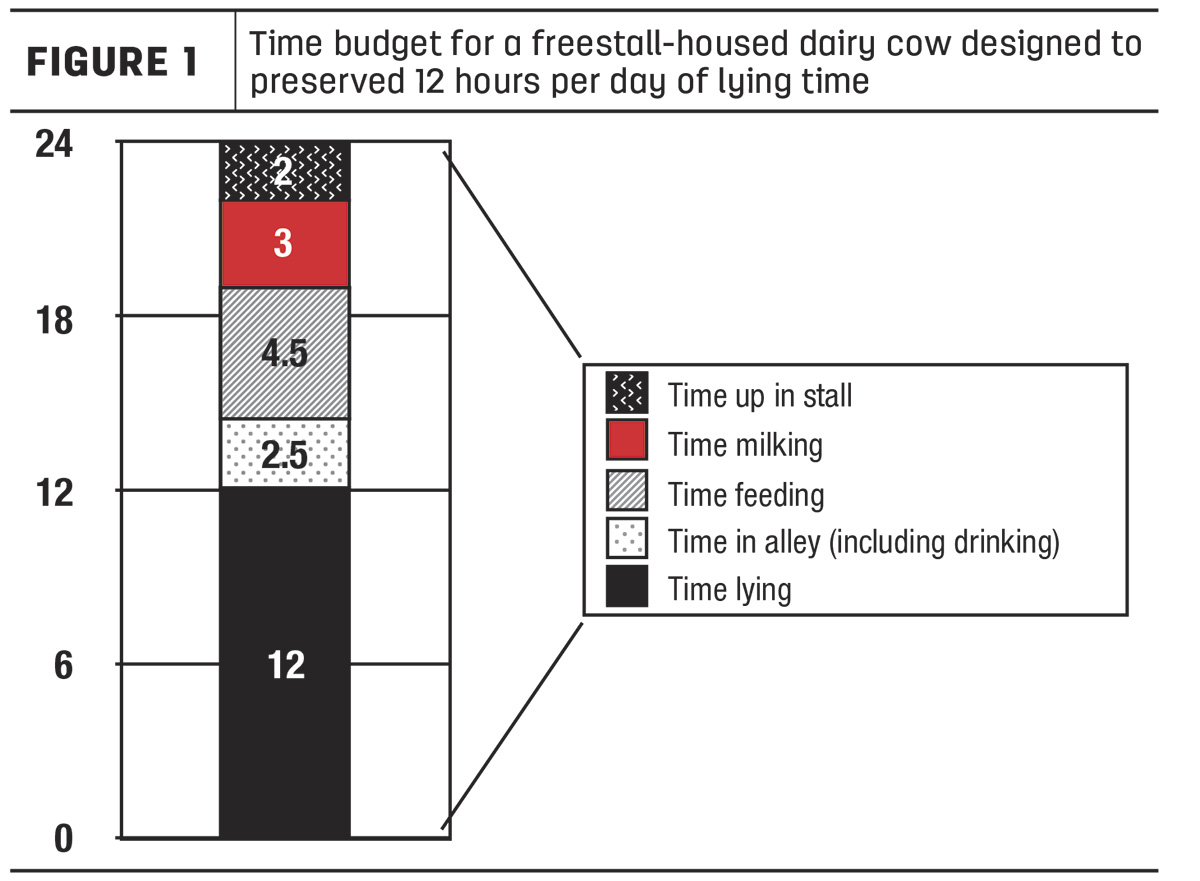

Under optimal conditions, we know that we can achieve average lying times per day in high-producing dairy herds of 11.5 to 12.5 hours per day or more (Figure 1).

In parlor-milked herds, we know that if we exceed total time out of the pen waiting to be milked each day of three to three-and-a-half hours per day, average lying time decreases. Farmers know that milking order is not random – the cows at the front of the holding area are always at the front, and the cows at the back are always at the back, and it is the cows at the back of the group that we are concerned about because they are the ones that lose time for resting and eating when milking time is prolonged.

In 16 commercial Wisconsin freestall-housed dairy herds, average time spent milking was 2.7 hours per day with a range from half an hour to six hours per day for individual cows. Extending the time waiting to be milked is a significant factor reducing lying times each day and increasing the risk for diseases, such as lameness. For that reason, we recommend sizing pen groups relative to a parlor throughput of no more than four turns per hour in 3X milking herds. We understand that efficient parlors can exceed that throughput, but we must allow for transfer time to and from the parlor to avoid exceeding three-and-a-half hours per day out of the pen for the last cows at the back of the group.

So is time waiting to be milked an issue in herds milked with an automated milking system? Advocates for robot milking describe a perfect scenario where cows choose when to rest, eat and milk throughout their day and create their own time budgets for these activities. Contrary to that ideal viewpoint, there are reports of lying times in automated milking system herds that are rather disappointing and certainly no better than those observed in parlor-milked herds. So, how long do cows spend waiting to be milked in these herds – and might this be one reason for a reduction in expected lying time?

We set out to investigate how long individual cows waited to be milked in two automated milking system herds – one with a free-flow system and the other with a milk-first, guided-flow traffic system. The two herds had similar pen layouts with one robot per pen and no more than 60 cows per robot with a mix of first-lactation and mature cows in various stages of lactation. Average time waiting to be milked was nearly identical between the two herds; an average of 1:28 hours per day in the free-flow herd and 1:24 hours per day in the guided-flow herd – significantly better than what we have observed in parlor-milked herds.

However, that was not the whole story. In parlor-milked herds, there is a finite time when the last cow gets milked – when the last cow enters the parlor and the next group comes up to be milked, determined by parlor throughput. This is not the case in an automated milking system herd. In both traffic systems, there were very efficient cows that waited no more than a few minutes per day to be milked – these are the cows living the ideal life, choosing what they want to do, when they want to do it. However, in the free-flow herd, one cow waited more than five hours per day, and in the guided-flow herd, one cow waited nearly eight hours per day to be milked. The issue that we see is not in the average but the distribution of waiting times, and in automated milking system herds there is a long tail – because there is no finite time for the last cow in the group to be milked, they just carry on waiting. Contrary to belief, cows do not generally go off to complete other tasks when they struggle to access the robot, specifically in a free-flow herd. Instead, they remain waiting to be milked – the motivation to be milked overriding other immediate needs.

As we have observed with parlor-milked herds, time waiting to be milked reduced lying time; in the free-flow herd, cows that exceeded two hours per day waiting to be milked in the robot spent 1.7 hours per day less lying down compared to cows with short waiting times. In guided-flow herds, we can set up gate alerts to let the caregiver know if there is a cow trapped in the commitment pen that has not been milked within 30 to 45 minutes so that we can intervene and assist the cow, but in free-flow herds we are unaware of these cows that are struggling to access the robot.

In automated milking system herds with any type of traffic system, we recommend the following actions to facilitate access to the robot and minimize waiting times:

- Avoid overstocking relative to the robot. The desire to be milked is not equal throughout the day, with periods of high and low visits to the robots making it difficult to determine the number of cows per robot based on a theoretical throughput based on average box time. For optimal cow performance, we recommend no more than 55 to 60 cows per robot.

- Design the robot entry point to protect the shoulder area of the cow waiting. A 4-foot-long stationary barrier prevents dominant cows from displacing subordinate ones at the robot entrance.

- Use robot designs where the cows exiting do not interfere with the cows that are waiting, such as a tollbooth layout.

- Group first-lactation heifers separate from older dominant cows if possible and train them how to use swing gates before calving.