University of Nebraska – Lincoln (UNL) researchers have recently identified two new genetic mutations: delayed blindness in Herefords, and bovine familial convulsions and ataxia (BFCA) in Angus cattle.

Understanding and identifying genetic mutations allows beef producers to make breeding decisions that avoid producing cattle affected by those mutations. Working toward that goal, UNL researchers have spent years studying genomics, identifying mutations and developing tests to help producers make those decisions.

The two most recently identified genetic mutations and the tools to address them will help producers make breeding decisions to reduce the health issues caused by delayed blindness and BFCA. These issues were identified because producers either reported to their breed associations or their local university, who then contacted UNL. That communication between breed associations and researchers is important for identifying genetic problems quickly and finding a solution to minimize the impact on the industry.

Herefords: Delayed blindness

Work between UNL researchers and the American Hereford Association led to a recently announced commercial test for a new genetic condition: delayed blindness.

The investigation began after several American Herefords were reported blind in both eyes, with presumed onset around 12 months old. The cattle were normal as calves and had no obvious eye injuries. All the blind cattle shared a common ancestor that appeared in each parent’s pedigree, leading to a suspected novel recessive mutation that causes the condition.

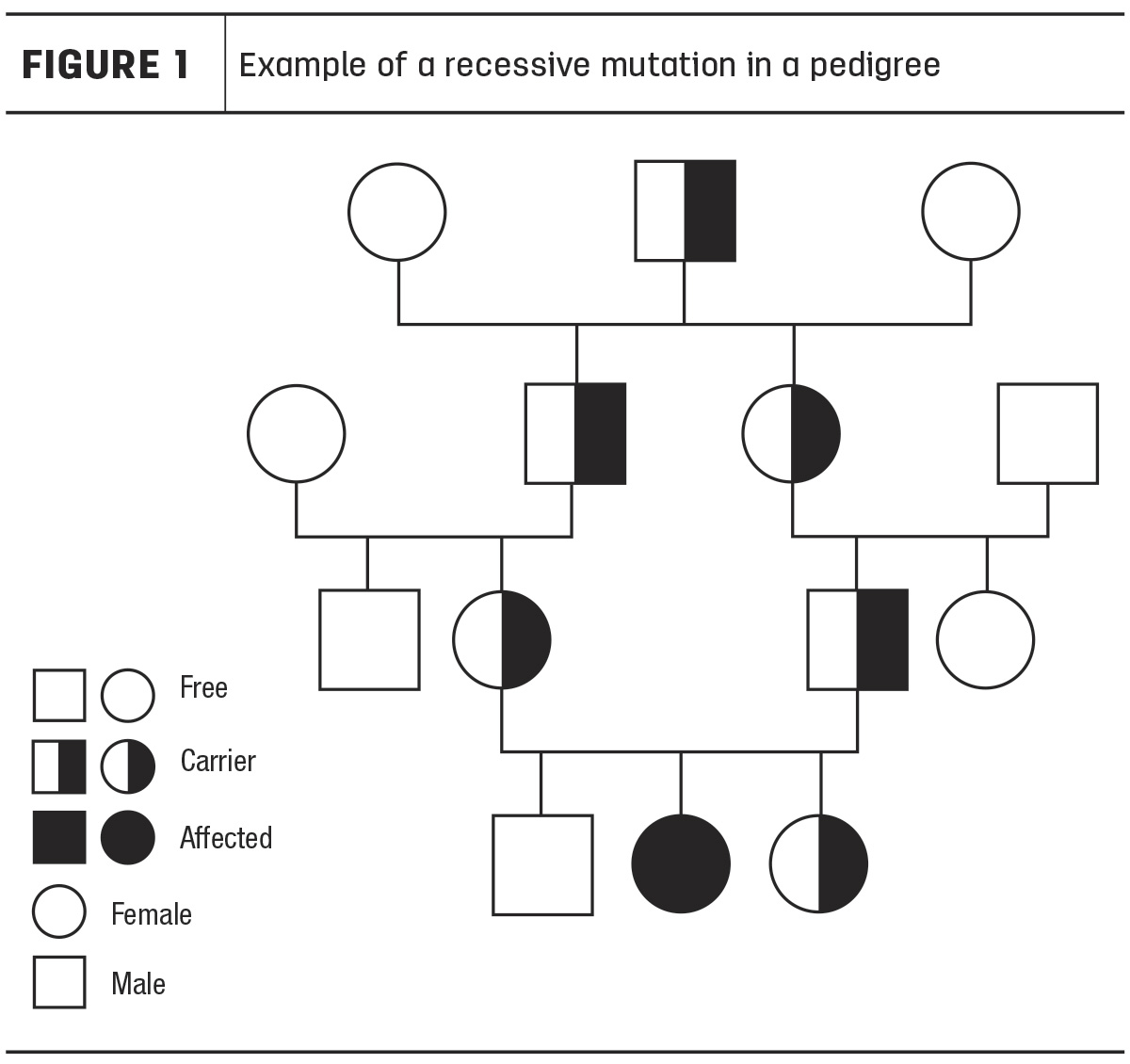

In a recessive mutation, the affected cattle need to inherit two copies of the mutation, one from each parent, both of which are related through a common ancestor (Figure 1).

To find the recessive mutation, DNA samples from the affected cattle, their dams and sires were collected with cooperation from the American Hereford Association. Samples from unaffected and unrelated cattle were used as controls. The DNA samples were sequenced to look for mutations shared among the affected cattle but that were not present in unrelated, normal cattle.

UNL researchers found a recessive mutation fitting the criteria in a gene associated with a condition that causes progressive blindness in humans (juvenile neuronal ceroid lipofuscinoses, or JNCL). The Nebraska Veterinary Diagnostic Center and collaborating board-certified veterinary ophthalmologists performed eye exams and histopathology that determined the retinas of these cattle were degenerating similarly to human JNCL.

Importantly, the investigation also determined that carriers of the delayed blindness mutation appeared normal. DNA samples from additional cattle (Hereford, Angus, Simmental and crossbred cattle) confirmed that only Herefords that descended from the identified common ancestor carried the mutation. Since the mutation is recessive, it was spread unknowingly by unaffected carriers until affected cattle were produced by carrier matings.

With enough evidence that the novel mutation is causing delayed blindness, a genetic test was developed for commercial use. This test allows producers to help manage the delayed blindness mutation within their herd to prevent mating of carriers.

Angus: Bovine familial convulsions and ataxia

Not all novel cattle mutations become prevalent in a breed. Nevertheless, genetic analyses can help detect and understand the issue. Through a collaboration with Tom Hairgrove, professor and extension veterinary specialist at Texas A&M University; and Jon Beever, professor and director of animal science at the University of Tennessee, UNL researchers identified a dominant mutation that causes bovine familial convulsions and ataxia (BFCA) in a single Angus herd. The founder had a single copy that he passed on to half of his offspring (Figure 2).

The calves that inherited the mutation experienced seizures and were unable to thrive. Through genetic investigation, researchers discovered that the mutation was only in the affected calves and their sire, though the sire was seemingly unaffected himself. Sometimes dominant mutations cause a less severe condition, or none in some animals, but can be detrimental to their offspring. It is also possible the sire may have “outgrown” issues he had as a calf, which would be unknown to the owners who purchased him after weaning.

Dominant conditions such as BFCA are often detected sooner than recessive ones such as delayed blindness due to their notable effect in the first generation. Although the sire was culled early on due to the frequency of affected calves he was producing, the investigation provided answers for the owner as to why this occurred.

Importance of genetics to beef producers

Genetic research like the cases studied by UNL helps producers avoid matings that may result in calves that fail to thrive or have other issues detrimental to their well-being or productivity. As in the BFCA example, genetics can also provide answers for producers when many calves from a single calf crop have a similar, detrimental condition.

It’s important to note that these issues can be investigated only when reported. Reporting possible issues to a breed association is a good practice. The breed association can track reports to identify an emerging issue. Many breed associations work with UNL to look into these reports, using the expertise at the Nebraska Veterinary Diagnostic Center to determine if the issue can be attributed to an environmental cause such as exposure to a toxin, viral infection or nutritional deficiency. If an environmental cause is not identified, the UNL Animal Genetics and Genomics Lab in the Department of Animal Science considers genetic conditions, as in the case of delayed blindness and BCFA. By using genetics, these detrimental mutations can be managed to continue improving herd performance while avoiding unfavorable genetic conditions.

This article was reprinted with permission from the University of Nebraska – Lincoln.