Mastitis is a complicated and costly problem for the dairy farmer. No simple solutions are available for its prevention. Some aspects are well understood and documented in scientific literature. Others are controversial and opinions are often presented as facts. However, from the dairy farm perspective, two simple product mandates are required – simplicity in use and cost.

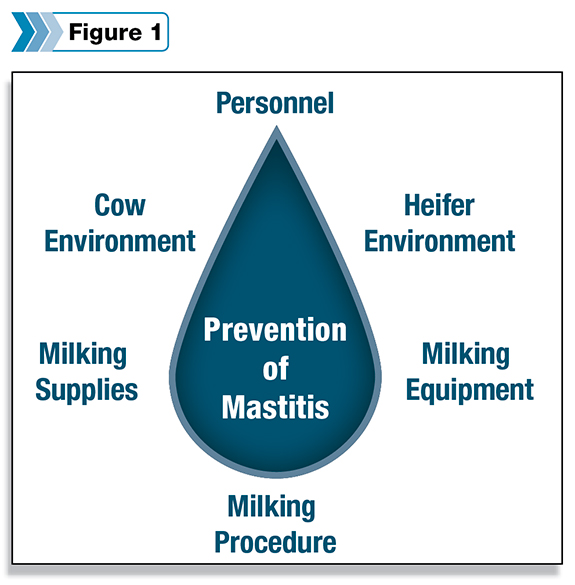

To simplify understanding of mastitis, one will need to appreciate it is a multifactoral outcome involving many elements ( Figure 1 ).

More than 100 different micro-organisms can cause mastitis, yet the route by which they reach the cow varies greatly.

When the udders of cows become infected, a host of expenses and losses occur: Milk must be discarded and production potential is reduced.

Animals sometimes must be culled. Potential superior genetics are lost. Profitability is reduced through treatment. Reproductive performance can be reduced.

Extra labor must be expended, and an immeasurable level of stress on management personnel occurs. These costs are estimated to be at least $185 per cow annually in the U.S.

Without mastitis, the lives of all dairy producers, and the lives of cows, would be much easier. Since there is mastitis, producers must know how to manage it to remain profitable and stay in business.

Mastitis occurs when the udder becomes inflamed because leukocytes, or somatic cells, are released into the mammary gland in response to invasion of the teat canal, usually by bacteria.

These bacteria multiply and produce toxins that cause injury to milk-secreting tissue and various ducts throughout the mammary gland.

Elevated leukocytes, or somatic cells, cause a reduction in milk production and alter milk composition. These changes, in turn, adversely affect quality and quantity of dairy products.

To manage mastitis, dairy producers must be willing to change old habits or ineffective and incorrect practices that may be causing or permitting new intramammary infections (IMIs) to occur.

A prime objective of all dairy farms should be determining which practices might cause mastitis and low-quality milk and then making the changes necessary to prevent the occurrence of those situations.

The milking parlor is the traffic circle of the dairy farm. It is a traffic junction, an obligatory passage, moving smoothly if well managed.

Adapted to the cows, the milking parlor is a tool to optimize milk production. Adapted to people, the parlor is an easy place to manage and can be a productive place for workers.

Mastitis prevention is based on the following scientifically proven principles:

1. Create a clean, stress-free environment for cows. For optimal milk production, oxytocin is best stimulated under a stress-free environment for cows. Starting with a clean stall and parlor will decrease the presence of mastitis-causing bacteria.

2. Remove all solids and clean teats. Cleaning the teats before attaching the milking machine is a very important step in preventing bacteria from getting into the teat canal during the milking process.

Environmental organisms such as Streptococcus uberis, Streptococcus dysgalactiae and the coliforms (E. coli, Klebsiella and Enterobacter) are in the soil and manure, which get onto teats. These contaminants must be cleaned off and the bacteria killed before attaching the milking unit.

If they are not, there is always a strong possibility that bacteria could be forced into the teat during the milking process, resulting in a new IMI.

Water is an excellent vehicle for transferring or transporting bacteria, so use water to wash only the heavily soiled teats and lower udder sidewalls. When water must be used, minimize the amount used and have the water pressure level set low.

Be sure the water hoses are flushed out before each milking so that stale water in the hoses that might contain Pseudomonas aeruginosa bacteria is removed and not sprayed onto teats.

If teats are consistently dirty, correct the causes (poorly maintained bedding in stalls, not cleaning alleys often enough, not enough stalls for the herd size, poorly maintained walkways to pastures or exercise lots, etc.).

3. Examine the udder. Look for chapped, cracked and bleeding teats. Examine and score teat ends. Do not use chapped, cracked or bleeding teats or teat ends. These teats are susceptible to new IMIs and should not be milked.

4. Use proven, effective pre-milking teat dips. Teat dips reduce the number of bacteria on teats and thereby help lower the number of new IMIs.

Germicidal teat dips have been proven in numerous research trials to be effective at killing bacteria on the teat surface and reducing the incidence of new udder infections. All dairy producers should routinely use them. Pre-dips should be left on the teats at least 20 seconds before wiping off.

We recommend that a proven, effective germicide be dipped onto the teats rather than sprayed, due to the likelihood that dips will be used more properly and provide better coverage than sprays.

Dip containers must be kept clean in order for the germicide to be effective. Dip cups should be cleaned between each milking or more often, if needed, depending on herd size and cow cleanliness, so they do not become âbacterial contamination cupsâ and spread mastitis to and between cows.

Dips remaining in the dip cups should be disposed of after each dipping session to further prevent the spread of mastitis-causing bacteria. There are many different brands and formulations of teat germicidal products on the market. Use only products that have been proven effective at killing bacteria on teats.

5. Use paper towels or reusable cloth towels to clean and dry teats. One paper or cloth towel should be used for each cow to wipe the teats clean and dry before the milking unit is attached.

Be sure teat ends are cleaned thoroughly so any solids on or around the teat opening are removed. Milking equipment needs a dry teat in order to have the best suction.

If teats are not sufficiently dry, chapping, pinching or bleeding may occur, leaving the cow further susceptible to mastitis-causing bacteria.

6. Fore-strip milk from each quarter. This practice should be done before attaching the milking unit to check for clinical infection. Fore-stripping stimulates oxytocin, which encourages milk let-down and increases milk flow rate.

Fore-stripping may be done before the teat dip is applied, and the teats are wiped clean and dry or after the teat dip is applied. Both ways work equally well in realizing the benefits of fore-stripping.

Fore-stripping has the potential in many dairy operations to improve milk quality and teat end health, reduce the rate of new IMIs and improve parlor performance.

7. Double dip with pre-dip. For even better results, double dipping is a good practice to add to your milking protocol and reduce somatic cell counts.

8. Use milking equipment properly. All personnel who use the milking equipment should be trained on how to properly attach, adjust and remove (if required) the milking unit.

Preventing air admission during the attachment process and adjusting the unit so it hangs properly under the cow are important in preventing or reducing new IMIs and realizing complete, even and rapid milkout.

Whether cows are milked from the side or between the rear legs, proper unit adjustment is required and needs to be observed closely. Quarters that do not get milked out completely should be left alone until the next milking.

Seldom should that procedure result in a clinical mastitis case. Reattaching the unit could do more potential harm. The practice of removing the inflation from one or perhaps two quarters that milk out fast prior to removing the entire milking unit from the cow should be avoided.

Removal of the milking unit from one or more of the quarters before milking is finished may cause air to leak into the claw, impacting the other attached quarters by teat-end impact.

When teat-end impacts occur, bacteria in the milk may be forced into the teat canals of the still-attached quarters and may result in a new IMI.

9. Monitor the milking process. Using milking machines properly is an important part of a milking parlor or milking barn routine, plus an important component of a mastitis management program.

Ensuring that staff is using machines properly and following protocol is important for healthy cows and a well-maintained farm.

Mastitis control and prevention is clearly attainable but requires diligence and the adoption of best practices. PD

Ira Weisberg

Head of Business Development

AquiLabs U.S.