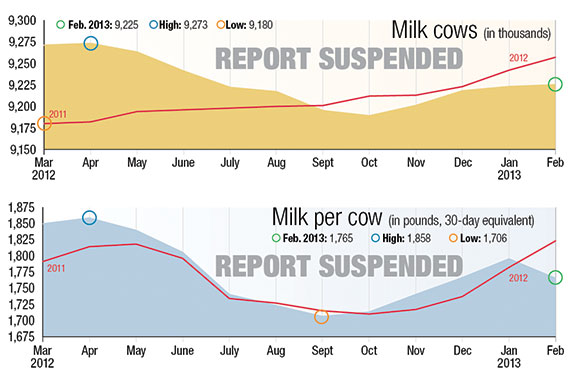

They say people don’t fully appreciate what they have until it’s gone. Seems true enough judging by the dairy industry’s reaction to a USDA plan to pull the plug on monthly milk production reports.

The USDA announced on March 12 that it would suspend its monthly milk production reports for the remainder of the fiscal year.

Budget cuts linked to sequestration were to blame, officials said.

Some industry groups including the National Milk Producers Federation and International Dairy Foods Association strongly objected, saying that elimination of the reports would reduce market transparency and make marketing decisions more difficult.

The USDA reconsidered and on April 3 announced that the National Agricultural Statistics Service would continue to issue monthly milk production estimates through the remainder of the fiscal year ending Sept. 30.

But be forewarned: The reports issued in the coming months will not contain as much information as they have in the past.

The reports will be based on “various administrative data,” not on actual producer surveys as before. That means dairy cow numbers and milk per cow statistics will not be available.

It’s possible that the monthly production reports will continue after the new fiscal year begins Oct. 1, but there’s no guarantee.

Some people in the industry worry about potential disruption to the futures markets, forward contracting and pricing if the USDA were to drop the monthly production reports entirely.

“Milk production data is fundamental to the transparency of the market and the generation of appropriate supply/demand pricing signals,” says economist Jon Hauser, Xcheque.com managing director and editor.

“To my mind the major impact of a lack of information is increased volatility – exactly the thing most farmers (and buyers) are complaining about,” he says. “If there is no indication of where production is or where it is heading, there is no brake on oversupply or no early indication of undersupply.”

The result would likely be higher peaks and deeper troughs in the pricing of both milk and commodities, Hauser says.

Not everyone was troubled by the news that the government might drop the monthly reports.

“Our view really is that it’s not a big deal,” says Scott Stewart, president of Stewart-Peterson Inc. “We don’t see this as affecting marketing decisions in a bad way.”

USDA milk production figures are about three weeks old by the time they’re released and are a lagging indicator at best, Stewart says.

“The flow of the milk has already been in the market. Everybody has seen it and felt it and it’s basically almost old news,” he says.

There are other information sources that people could turn to if the monthly milk production reports ever disappeared. Producers and traders would not be left in the dark, Stewart says.

The USDA’s weekly survey on block cheese, butter and powder will still be there, and the Chicago Mercantile Exchange will still issue a daily dairy report.

“The flow and activity that you see on a day-to-day and week-to-week basis is really what matters,” Stewart says.

Old information is actually worse than no information at all because it can distract and mislead people, he says. Stewart believes a sound risk management strategy is much more valuable than all the data that a person can gather.

“The focus of marketing is laying out a good strategy and managing the opportunities and risks that unfold before you. It doesn’t have anything to do with all this information,” he says.

When the USDA made its original announcement in March, milk production stood out as the only major category affected by sequestration cuts. That had some people in the industry wondering about a possible motive.

Alan Levitt, vice president of communications for the U.S. Dairy Export Council, says it appeared to be a deliberate attempt “to try to inflict the most pain on the most people, to draw attention to the fact that our elected representatives won’t do their job.

“(NASS) couldn’t have honestly thought that cutting the milk production report was a good thing to do,” he says. “I have to assume they did it kind of out of spite. That’s the only logical conclusion I can draw from their action.”

This isn’t the first time that the government has considered cutbacks to agricultural reports. In 2011, the NASS Advisory Committee on Agricultural Statistics recommended reduced frequency of reports – but not their elimination – as a way to deal with budget cuts.

USDA’s milk production reports date back to at least the 1920s and have become a widely watched benchmark. (The U.S. produced 89 billion pounds of milk in 1924, compared with 200 billion pounds last year.)

Levitt uses the monthly USDA data to prepare outlook reports on a regular basis.

“The milk production report is probably the most important of all the USDA reports,” he says. Its elimination would have a huge impact, he believes.

Levitt thinks it’s embarrassing that the U.S. is in danger of losing its monthly milk report while other countries such as Argentina and New Zealand don’t seem to have a problem.

“This affects the way we do business. It affects the way people outside our borders look at us,” he says.

Even a temporary suspension of the monthly milk production reports could be detrimental, some believe.

“You won’t be able to make the comparisons that are so critical to providing context to any number,” Levitt says. “If you don’t have those comparisons, that’s problematic. People would get around that, but it’s still not good.”

Levitt acknowledges that the industry has probably become too reliant on the government for information. If the USDA can no longer be counted on to gather the data, maybe the industry should act on its own, he says.

After all, the dairy industry already has all of the information. The USDA simply aggregates it.

“Every co-op knows how much milk it is taking in. It really wouldn’t take that much for someone to just cull all that data from the co-ops if the industry would just trust each other and work together. We wouldn’t need to have the government do it for us,” he says.

Perhaps back in the ’20s or ’30s the government was the best entity to aggregate the data, but technology has changed, Levitt says.

“There shouldn’t be any reason that someone couldn’t put together a quick (computer) program to cull that information,” he says.

For now, the industry will continue to have access to limited USDA monthly milk production data. The question producers and analysts should be asking themselves is: How much longer? PD

Wilkins is a freelance writer based in Twin Falls, Idaho.