Commingling, or mixing cattle from multiple sources, occurs every day in the U.S. at livestock auctions, through direct cattle purchases, at shows and fairs and through contract rearing. In fact, almost 40 percent of dairy operations brought on new additions and commingled cattle in 2006, and about 70 percent of dairy heifer-raising operations commingled heifers or allowed nose-to-nose contact among heifers from multiple sources during 2010.

Producers realize there are cattle health risks associated with purchasing new cattle or allowing cattle to have contact with cattle from other operations.

But how big are the risks? With some diseases such as tuberculosis (TB), the risks can be very high – the herd destroyed – but the probability of TB introduction is very low.

With other more common diseases such as bovine respiratory disease (BRD) or bovine viral diarrhea (BVD), the risks associated with introduction varies depending on the initial status of the herd, but the probability of introducing these diseases is much higher than that for TB.

Commingling cattle almost always involves transportation, which increases stress, making cattle more prone to infection. In addition, because of the stress of transportation, cattle subclinically infected with a disease (showing no signs) may convert to being clinically infected (showing signs) and shed infectious agents.

Since the risks associated with purchasing or raising cattle from multiple sources are well established, what steps can producers take to minimize these risks? Or stated another way: How can an operation improve its biosecurity? The good news is there are multiple steps that reduce the risk of introducing new diseases to a herd.

The following are five steps to decrease the risk of introducing new diseases to your herd:

1. Maintain a ‘closed’ herd – Don’t purchase or allow contact with cattle from other operations

Since many infectious cattle diseases require direct contact to spread from animal to animal, removing the opportunity for contact with cattle from other operations is the best method of preventing disease transmission.

2. Determine the disease status of the source and/or contact herds

Some herds can’t remain closed and have to either purchase new additions or allow their cattle to have contact with other cattle. In these cases, knowing the disease status of the source herd or contact herd is one of the best ways to keep from acquiring new diseases.

For instance, cattle from a herd that has eliminated BVD or has achieved test-negative status in the Johne’s disease program present a lower risk than cattle from herds that have not tested for these diseases.

3. Quarantine new additions

Once the decision is made to acquire new additions and the disease status of the source herd has been determined, the most commonly recommended method of preventing disease transmission is to quarantine new animals.

Quarantine is the physical separation of new arrivals from the home herd. A 30-day quarantine is recommended, which allows time for observing the new cattle in order to determine if they are incubating diseases that could affect the home herd.

Within 30 days many, but not all, infectious diseases the new cattle may be harboring will become evident.

Quarantine, however, can be difficult to institute at the farm level, depending on the type of operation and/or the type of cattle brought on. For instance, dairies that bring on lactating cows don’t usually have the luxury of a separate milking facility for quarantined cows.

In addition, large dairy heifer-raising operations that raise preweaned calves from several different operations may not have a feasible way of quarantining new calves.

Specific questions regarding quarantine practices for heifers were not asked during the NAHMS 2011 study; however, the study did find that almost 60 percent of operations with 1,000 or more dairy heifers raised heifers for five or more clients (i.e. sources), and almost 15 percent of operations raised heifers for 10 or more clients.

As noted previously, commingling cattle was common on these operations. One option for increasing biosecurity may be for dairies to purchase bred heifers instead of lactating cows. Heifers can be quarantined, and heifer-raising operations could dedicate separate areas for each client’s calves.

4. Test new additions for diseases important to the health of your herd

Keeping new arrivals separated from the home herd for a short period also provides time to implement other practices that reduce the risk of disease transmission. Knowing the specific disease status of the source herd is not always possible, so individual animal testing may be the only option.

Testing takes time, and cattle shouldn’t be commingled until test results are available. Half of the dairy heifer-raising operations participating in the 2011 study tested heifers for at least one disease.

It is clear from the study that some producers recognize disease risks, since a higher percentage of operations with 1,000 or more dairy heifers performed disease testing compared with operations with less than 100 heifers.

As one might predict, BVD was the disease for which testing was most commonly performed (almost 40 percent of operations). Interestingly, testing for TB was performed on more than 25 percent of heifer-raising operations, likely because of the requirements for moving animals across state lines.

5. Vaccinate new additions and the home herd to boost immunity

In addition to testing, the quarantine period also provides a window for protecting the new arrivals from diseases in the home herd.

Many times we don’t think about disease spreading from the home herd to the new additions, but it does happen. Vaccinating new arrivals during quarantine gives the cattle time to develop resistance to diseases before being introduced to the home herd.

Earlier, we talked about the risks associated with BRD when commingling cattle. Transporting cattle can be stressful for animals and is also a known risk factor for BRD, which is why it is commonly referred to as “shipping fever.”

Interestingly, transport distance isn’t clearly associated with BRD risk. The animals’ age at the time of transportation has also been associated with the risk of BRD, as younger calves appear to be more susceptible, which represents a real challenge for heifer-raising operations with preweaned calves.

So, did NAHMS find a greater incidence of respiratory disease on heifer-raising operations where calves were exposed to transportation and commingling risk factors? The answer is maybe.

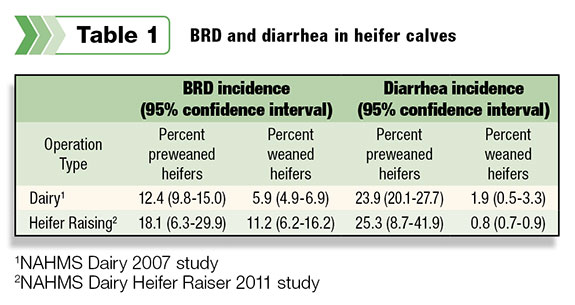

Table 1 compares the mean and 95 percent confidence intervals for BRD and diarrhea in heifer calves on dairy operations with heifer calves on heifer-raising operations.

The mean percentage of heifers with BRD was higher for heifer-raising operations than dairies, but the confidence intervals overlap so the estimates are not statistically different, likely due to the small sample size of the heifer-raiser study.

If there is a true difference in the mean incidence of BRD between dairy operations and dairy heifer-raising operations, it might be due to more BRD, better records of calf health or contractual agreements with source dairies (e.g. dairy pays for treatments).

The estimates for diarrhea or other digestive diseases were very similar for both operation types within heifer class (preweaned vs. weaned).

The bottom line is that the cattle industry, including dairy heifer-raising operations, is and will continue to commingle cattle from multiple operations. Given this fact, it is important to identify opportunities and implement the most cost-effective methods to reduce the risk of disease transmission.

To date, the most effective methods available include knowing the disease status of the source herd, quarantining new additions and watching for clinical signs of disease, and testing and vaccinating new additions. Producers should work with their veterinarian to determine the biosecurity plan that best protects their herd. PD

All NAHMS reports are available on the web. Click here to view these reports.

References omitted due to space but are available upon request. Click here to email an editor.

Photo by PD staff.

Jason Lombard

Dairy Specialist

National Animal Health Monitoring System