On the dairy, the ability to get cows pregnant is the pivot point of profitability. Herds with sound reproduction programs are able to capture opportunities for milk production and genetic progress, while those that struggle to get cows bred back in a timely manner face the costly consequences of longer days open, increased breeding and replacement costs, and risk of reproduction-related culling.

According to Alex Souza, Ph.D., DVM, the use of timed A.I. through various versions of synchronization programs has been linked to improvements in reproductive efficiency.

“And that might be the difference between continuing to milk cows or not,” says Souza, who is a University of California dairy adviser for Kern and Tulare counties.

His research at the University of Wisconsin – Madison examined the utilization of synchronization programs among U.S. dairy herds as well as the impact of such programs on reproductive performance and culling rate among Wisconsin herds.

Who is using timed A.I.?

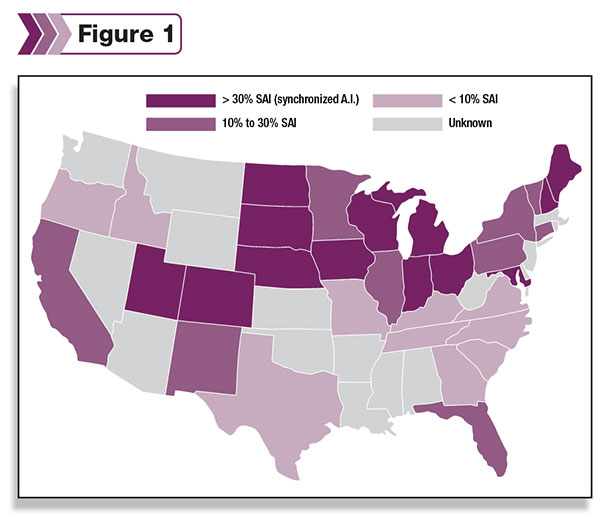

Across U.S. dairy herds, nearly 30 percent of A.I. breeding is performed in accordance to a synchronization program. This figure comes from Souza’s analysis of DHIA reproductive records, which included more than one million records from 40 states (see Figure 1 ).

However, the herds in the Midwest and eastern U.S. have adopted synchronized breeding protocols more than those in western and southern regions. Less than 10 percent of breedings follow synchronization in states like Texas, Idaho and Oregon, compared to Wisconsin where more than half of the inseminations are timed.

Impact of timed A.I. on reproductive performance and culling

Honing in on Wisconsin herds, Souza next looked at the impact of timed A.I. on reproductive performance and culling rate based on real data from the Dairy Comp 305 backups of 200 herds.

According to his findings, herds using synchronization programs were more successful at getting cows pregnant. The use of timed A.I. protocols was associated with better estrus detection and conception rates.

“As a result, 62 percent of herds that were using synchronization [67 percent of the time or more] had pregnancy rates of 18 percent or better,” Souza notes. He adds that timed A.I. protocols like Double OvSynch and G6G have been especially important tools in achieving pregnancies in anovulatory cows, a challenge particularly faced by higher-producing herds.

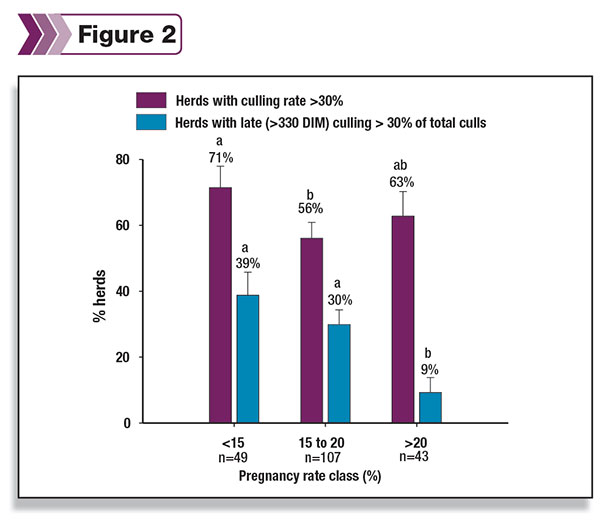

In Souza’s study of Wisconsin herds, there was no significant difference in overall culling between herds with low 21-day PR compared to those with higher 21-day PR, but the type of cows that are culled differs (see Figure 2 ).

“One interesting thing that we found is that when we look at reproductive efficiency, culling rates were not related to how efficient you are at getting cows pregnant,” Souza states.

“One interesting thing that we found is that when we look at reproductive efficiency, culling rates were not related to how efficient you are at getting cows pregnant,” Souza states.

Herds with solid reproduction programs often have a burgeoning crop of replacements ready to hit the milking string. This affords the luxury of selective culling, he explains. Cows may be culled based on poor traits such as an undesirable udder or legs.

On the contrary, herds that struggle to get cows pregnant are more likely to hold onto them because a replacement is not available. Thus, these problem-breeders remain in the herd until late in lactation and are then culled for poor reproduction.

“Those herds doing well with reproduction don’t cull cows at later stages of lactation because they are not forced to, and they don’t have as many cows finishing their lactation open,” Souza adds. “Those herds who are not doing as well are forced to cull late in lactation.”

The statistics also showed a correlation between greater use of timed A.I. and higher-producing herds.

“There was a positive correlation between the use of synchronization and 305 ME,” states Souza. “We found that high-producing herds are using more synchronization than low-producing herds.”

However, this observation only holds true up to a certain size. “We see this trend very clearly for herds up to 1,000 cows in milk,” he adds. “At 2,000 cows, it starts to come back down.”

He cites the reason for this trend to be the increased labor associated with breeding a large number of synched cows on the same day. A herd of 2,000 cows, for example, may have to breed as many as 150 cows on a single day. These herds tend to find tail chalking or heat-detection devices more useful.

Synchronization protocols and profitability

The ability to get cows pregnant is paramount in the overall profitability of a dairy. As Souza points out, it always comes down to economics.

With each percentage point of improvement to pregnancy rate worth as much as $35 per cow per year, significant gains can be achieved.

To put that into perspective, if a herd with 500 milking cows improved from 15 percent to 20 percent PR, that would add up to $87,500 of additional income. This figure accounts for factors such as reduction in expenses related to culling and increases in milk production related to overall herd performance.

“If a producer can invest a little more into reproduction, it will be better for them financially in the long run,” he says, adding that the cost of hormones and vet checks related to synchronization programs are usually less than 3 percent of the farm budget on an annual basis. “If synchronization is the solution for a herd, then being a little more aggressive with reproduction is not costing you.”

Improved reproductive performance also goes hand-in-hand with genetic progress.

“It is a hard selling point because it takes a year to see returns, but you can have more replacements two years down the road and a better herd genetically five years down the road,” he says. “If you plan to stay in business, it pays for itself.” PD

Peggy Coffeen

Editor

Progressive Dairyman