For the fresh cow, the entire transition period is a series of stress events.

From decreased dry matter intake close-up to challenges with rehydration and re-establishment of feed intake post-calving, the dairy producer needs solutions that encourage a healthy recovery and optimal lactation performance.

One of the most fundamental needs of the post-calving cow is returning to a proper hydration status. With calving fluid and tissue loss approximately equal to the weight of the calf, water intake is clearly critical. However, what isn’t often understood is how the combination of proper hydration and nutrition is required to work together in order to optimize recovery.

The rumen holding tank

The rumen serves as a reservoir that releases consumed water to the body fluid compartments via osmotic pressure and with the help of microscopic pumps located at the base of gut villi. Electrolytes and other nutrients create osmotic pressure in order to continuously supply cells with fluid for normal functions.

If the body does not have enough fluids, then the amount of nutrients transferred to the cells (for metabolism, etc.) is greatly reduced. Therefore, managing the water content in the rumen is important for maintaining normal rumen fluid volume as well as other body fluid reserves and metabolism.

Post-calving nutrient requirements

-

Calcium – Every new lactation challenges the cow’s ability to maintain adequate blood calcium levels. Healthy cows have 8 to 10 grams of calcium in their blood, but producing milk requires significant amounts of additional calcium – and colostrum production alone demands 20 to 30 grams of calcium in the first day.

Blood calcium is required for normal muscle and nerve function – especially as it relates to strength and gastrointestinal motility. Without supplemental dietary calcium, the cow’s body pulls calcium from bones to compensate. This results in a negative calcium balance (hypocalcemia) that could continue for roughly the first 90 days of lactation. Subclinical hypocalcemia is believed to affect 50 percent of cows in their second lactation.

-

Magnesium – Magnesium is needed to metabolize calcium and, therefore, critical to helping prevent hypocalcemia. Since the cow’s magnesium level is dependent on diet alone, a deficiency can easily occur when there is a natural drop in dry matter intake, such as when a cow is close-up or immediately post-calving.

Additionally, a magnesium deficiency (hypomagnesemia) can occur when rumen pH rises – placing continued emphasis on improving dry matter intake. Magnesium needs to be fed at levels up to four times higher than normal blood magnesium levels to ensure efficacy in absorption.

-

Potassium – Cows do not have the ability to manage potassium levels in their bloodstream and therefore rely on diet input, along with urine and fecal output, to regulate. The body’s supply of potassium can quickly exhaust post-calving, leading to metabolic disorders like ketosis.

Potassium is the primary electrolyte responsible for intracellular energy mobilization and utilization. In addition, it is responsible for the fluid balance within cells and for a proper body function. In fact, the absence of adequate amounts of potassium (hypokalemia) affects smooth muscle contractions that can lead to issues related to retained placentas. The combination of low feed intake and dehydration post-calving leave the cow deficient, and therefore supplementation is required to ensure recovery and sufficient support for cell activity.

Abomasal disorders and the effect of dehydration

Post-calving, there is more room for the abomasum to “move around” due to space now available without the calf. Encouraging immediate water intake helps to “anchor” the rumen in place and reduces the chance of displacement. Water intake also provides a necessary mechanism for gut function and nutrient dispersion.

However, due to continued depression in appetite, cows also may not drink right away or in amounts necessary for gut stability or recovery. Additionally, in the presence of even low levels of dehydration, another contributor to abomasal displacement is suppressed appetite and the resulting imbalance of essential nutrients.

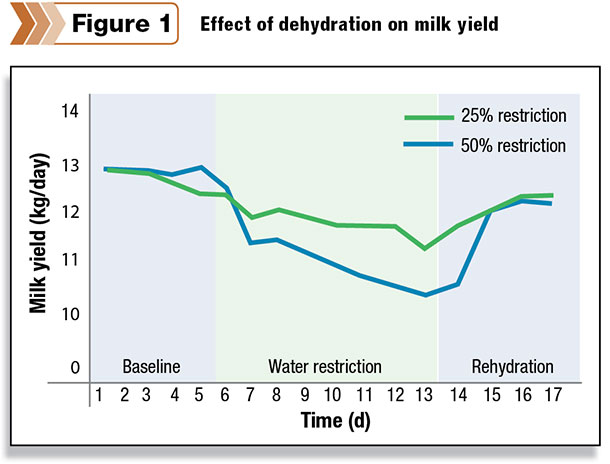

Dehydrated animals also have a lower dry matter and energy intake, which usually is compensated by lower milk production (Figure 1) in an attempt to control the energy balance.

Recent research results suggest that lower potassium levels in blood were associated with low chloride, rise in blood pH (alkalemia), low feed intake with high amount of milk produced, low circulating blood (hypovolemia) and higher blood glucose (hyperglycemia) in lactating dairy cows.

Recent research results suggest that lower potassium levels in blood were associated with low chloride, rise in blood pH (alkalemia), low feed intake with high amount of milk produced, low circulating blood (hypovolemia) and higher blood glucose (hyperglycemia) in lactating dairy cows.

Treatment for potassium deficiency should include surgical correction of abomasal displacement, increased dietary potassium intake via dietary dry matter intake or oral administration of potassium chloride and correction of the rest of the parameters.

Additional research shows that 38 percent of cows with left displacement of abomasums showed clinical symptoms of dehydration, where 57 percent of cows with right abomasal displacement showed some degree of dehydration.

Furthermore, cows with either abomasal volvulus or abomasal impaction were moderately to severely dehydrated in 85 percent of cases on average. Additionally, cows experiencing abomasal impaction were declared to have a “profound drop in potassium and chloride levels.”

Hydration is more than just consuming water

In all mammals, it is widely recognized that proper hydration is a physiological requirement for maintaining overall health status – for transport of nutrients, to boost the immune system and many other functions. Hydration starts at the cellular level, and requires the correct balance of electrolytes and energy, but note that the signs of dehydration are not always easy to identify.

Electrolytes can be added to the ration on an as-needed basis to improve fluid efficiency due to their role in helping promote nutrient flow and balance. When calculating replacement fluids, it’s important to consider maintenance requirements, production needs and fluid losses due to calving, heat stress, sweat, sickness or other challenges.

By way of example, to maintain normal cellular functions, a 450-kilogram cow (about 992 pounds) requires 44 kilograms (about 97 pounds) of water on a daily basis. Some of this water comes from their feed ration (10 to 30 percent) and the balance from daily water volume intake (usually 8 to 9 percent of their total bodyweight).

For a lactating cow, each 5 kilograms (about 11 pounds) of milk produced requires an additional 4 kilograms (about 9 pounds) of water over maintenance requirements.

Post-calving, reducing the chance of metabolic issues through nutrient supplementation with electrolytes and energy is critical – and products that incorporate yeast can help improve intake.

It is clear rehydration is a key requirement in maximizing nutrient utilization, establishing good hydration health status and optimizing lactation. Many post-calving challenges can be mitigated with the right nutrition delivered at the right time. PD

References omitted but are available upon request. Click here to email an editor.

PHOTO: Cow with her new calf. Photo provided by TechMix Europe.

-

Rodrigo Garcia

- Technical Services

- International – Ruminants TechMix Europe