Fluctuations in the prime rate are of great concern to agricultural operations. The prime rate has traditionally been the interest rate that banks charge their best customers, and it strongly influences the setting of other interest rates. The prime rate varies little among banks, and banks generally adjust their rates at the same time. As a result, agricultural managers are among the many now asking: “Where are interest rates headed?”

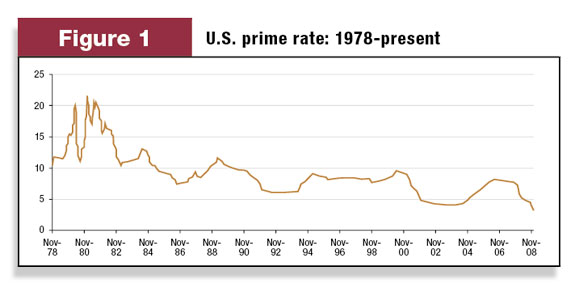

Figure 1 , showing changes in the prime rate since 1978, demonstrates that the answer has been generally downward – with only a few, brief exceptions. However, since the financial crisis in the fall of 2008, the prime rate has remained unchanged at 3.25 percent. This stability indicates that further reductions will not happen and, in fact, suggests that increases seem almost certain. The question is not “Will rates go higher?” but rather, “When will rates go higher?”

Variable rates versus fixed rates

With a variable rate, the prime rate can actually change as often as daily; but it actually changes monthly or quarterly because it is indexed from the Federal Funds Rate, which the Federal Reserve Board sets on a monthly basis. Other variable rates may be tied to U.S. Treasury notes or bonds or other financial instruments that move up and down. Most, if not all, of these variable rates are influenced by Fed policy; most short-term borrowings, such as revolving and/or operating lines of credit, are variable rate loans.

This means that agricultural operators must be mindful of Fed policy and the prime rate when determining how, and how much, to borrow.

Fixed-rate loans are normally made or offered on intermediate (three- to seven-year) terms, and loans for longer than seven years are considered long term. Long-term loans are specifically secured with equipment, animals and land as collateral; and because such loans are intended to finance assets that are used over the intermediate and long term, they can be fixed for a period of time. Interest rates for fixed-rate financing is normally higher than for variable-rate financing, because the commitment from the bank is being made for a longer period of time, and this tends to increase the risk of principal repayment.

Normally having a combination of variable- and fixed-rate debt is desirable for a dairy operation. However, managers of each operation will have different needs to consider. They may also have different experiences and attitudes.

Generational differences

As I work with various agricultural operations that have multiple generations in management, I hear widely varying attitudes on fixed-rate versus variable-rate borrowing.

Looking back at the historical chart on the U.S. prime rate, it’s easy to see why.

Those people in active farm management today who were already farming back in the 1978-to-1982 time frame (and who are now around 55 and older) will almost always favor a fixed rate on intermediate- and long-term debt. These veteran operators will often recall the painful experiences they (or they and their parents) endured when variable rates went as high as 20 percent and much of their debt was variable. This generation will in most cases be willing to pay a small premium for the peace of mind they receive from knowing that they have a fixed rate on intermediate- and longer-term debt.

The younger generation (around 35 and younger) did not experience the same pain. They missed those painful interest-rate jumps, so they look at the same chart and reflect on how interest rates have been between 5 and 10 percent over most of the last 30 years. Therefore, they tend to believe that relatively low variable rates will continue indefinitely. Consequently, operators of this generation will normally opt for a variable rate. They believe they will save money over the long haul because a fixed rate is generally higher and history shows rates won’t change much.

Both of these age groups bring very valid points to the discussion of fixed versus variable interest rates. The “older” generation believes that some of the factors that drove up variable rates in the late 1970s could return and create financial havoc again. They believe the best insurance against higher rates is to fix as much debt as possible. Meanwhile, members of the “younger” generation look at recent history and assume that it will continue. As a result, they believe that variable rates are a better deal. Naturally, the balanced view calls for a strategy of having a portion of debt at a fixed rate and the remainder at a variable rate – a view that each operation should consider and apply to its own situation. Generally speaking, operating debt and a portion of intermediate-term debt should be variable, and the remainder of intermediate-term debt and long-term debt can be fixed.

Looking forward

Interest rates will go higher in the next 12 months.

Federal Reserve policy, mid-term elections and other world financial events will dictate the exact time frame for rate increases as the U.S. business cycle improves and some inflationary pressures resume in the economy. As a forward-thinking dairyman, you should talk to your banker about the interest rates and loan structures you have and see if some changes can be made.

Generally, some combination of variable- and fixed-rate financing will make sense for you. Make sure you take advantage of this opportunity over the next six to 12 months, because it can impact your profitability over the longer term. PD

-

Larry Davis

- Vice President

- KeyBank Food and Agribusiness Team

- Email Larry Davis