Many of the challenges the transition cow experiences are the result of internal changes to the rumen environment and hormone balance. By looking inside the cow’s rumen and examining metabolic pathways, we can better understand how to navigate these challenges through proper ration formulation, leading to a healthier, more productive and more profitable milking herd.

A rapidly changing internal environment

There are a multitude of changes taking place in the rumen and the bloodstream during the transition period, which refers to the three weeks before through the three weeks after calving. While we may be familiar with the major changes – calving, onset of lactation and pen swaps – internal physiological changes are happening at the same time.

• Hormone levels fluctuate

The transition period is marked by major hormonal changes that directly lead to reduced dry matter intake (DMI). These hormone changes include:

• Insulin levels continually decline until calving. Insulin causes cells in the liver, muscle and fat tissue to take up glucose from the blood and store it. When insulin levels are low, the body begins to use fat reserves as its main energy source.

• Progesterone levels, which remain high throughout gestation, rapidly decline postpartum. Progesterone helps maintain pregnancy, so as calving approaches the need for the hormone diminishes.

• Estrogen and glucocorticoid levels change, which contributes to the decline in DMI and coordinates metabolic changes that mobilize fat reserves.

• Rumen microbe populations change

Two microbial populations are frequently found in the rumen. Cellulolytic microbes thrive on fiber sources while amylolytic bacteria flourish in more acidic environments. When the ration abruptly changes from a high-fiber to a high-energy formulation at calving, the cellulolytic bacteria cannot utilize the lactate in the rumen. While amylolytic can utilize lactate, it can take three to four weeks for the population to grow to capacity. This can increase the accumulation of lactate, leading to a greater chance of rumen acidosis.

• Rumen papillae shrink

Papillae are responsible for absorbing volatile fatty acids (VFAs) in the rumen. During the dry period, papillae can decrease in size by half. When VFA production increases significantly at calving, levels can far exceed absorption capacity, which can lead to rumen acidosis, reduced DMI and feed digestibility and increased risk of laminitis after calving.

• Calf nutritional needs increase

Cows require 1.3 to 1.5 times their regular maintenance needs by the end of gestation. As the calf’s nutrition requirements increase, cows require more energy than they can consume, resulting in a negative energy balance and loss of body condition.

Nutritional strategies for transition success

The wide variety of ongoing challenges that take place during the transition period can be counteracted with effective nutrition solutions. To help your herd more effectively navigate the transition period, use these ration-balancing guidelines:

• Supply the right nutrients at the right levels

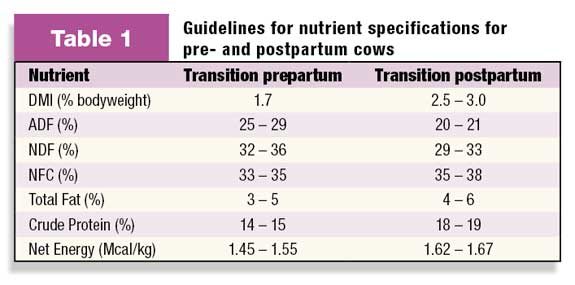

Nutrient requirements shift dramatically throughout the transition period. The following table outlines key nutrients and the levels that should be fed pre- and postpartum. Higher-fiber diets should continue to be fed prior to calving while fat, energy and protein levels should increase after calving.

• Use the right source of energy

Non-fiber carbohydrate (NFC) levels should increase gradually during the transition period to enhance energy density and rumen papillary development. NFC fermentation produces propionic acid, which supplies additional glucose to the cow and minimizes glycogen breakdown commonly associated with the transition period.

• Supply the right amino acid profile

The uterus uses as much as 72 percent of the amino acids in circulation by the end of gestation. When insufficient protein and amino acids are available, the cow will mobilize her limited protein reserves from tissues and muscle. High levels of dietary protein are critical to maintain, rather than use, protein reserves to support milk production postpartum.

• Balance for dietary cation-anion difference (DCAD)

Research confirms reducing DCAD prepartum to -8 to -12 meq/100g ration dry matter dramatically reduces the risk for milk fever and subclinical milk fever by improving the transfer of calcium from the bone to the bloodstream. The reduction of these diseases reduces the risk factors associated with displaced abomasums, retained placenta and ketosis and has been shown to increase DMI after calving. Postpartum, the cow is faced with high quantities of metabolic acids, which, if not buffered, could lead to reduced performance and DMI, and increased risks of other diseases including laminitis. Increasing DCAD to +35 to +45 meq/100g ration dry matter postpartum can provide the potassium needed for optimized milk and component production.

While managing the transition cow can be challenging, she represents the potential for a healthy, productive and profitable herd. Just how well your cows respond to your transition nutrition and management program is critical for success throughout the entire lactation. By formulating a nutrient-dense ration that your herd can’t refuse, you can successfully navigate the transition while your herd reaches peak performance potential. PD

References omitted due to space but are available upon request by sending an email to editor@progressivediary.com .

-

Elliot Block

- ARM & HAMMER

- Animal Nutrition

- Email Elliot Block