Grasshoppers are a visible, frustrating pest of rangeland and field crops. While we do not typically encounter spectacular, widespread grasshopper outbreaks like those seen in the Great Plains 100 years ago, they occasionally build up in numbers and cause problems over hundreds of thousands of acres of rangeland, pasture and row-crops.

It is a challenge to manage grasshoppers because it is difficult to predict if, and when, they will become a problem.

Often large numbers of grasshopper nymphs hatch in an area, but as time, weather and natural enemies take their toll, they generally fail to develop into a severe problem.

Grasshoppers can damage crops in many states, but are more likely to become a threat in areas that receive less than 30 inches of annual rainfall.

In addition, the timing of rainfall can substantially lower survival of eggs and nymphs in a given area. Thus, we sometimes see grasshoppers become a problem in isolated pockets and then subside.

In rangeland and pastures, grasshopper problems develop from a “complex” of species that tend to occur together and build in numbers large enough to cause damage.

The grasshopper life cycle

Grasshoppers produce one generation each year and have three stages: the egg, nymph and adult. The majority of grasshoppers overwinter as eggs, but a few overwinter as immature nymphs.

In late summer and fall, eggs are deposited in the soil in “pods” that contain from eight to 30 eggs. Embryos begin to develop, become “quiescent” through the winter and resume development in spring.

Eggs hatch in the spring, with specific hatching time affected by weather, especially soil temperature. Each species develops at its own rate, so we tend to see a continuous flush of hatching grasshoppers over several months.

Cold winters have little effect on eggs because the pod and surrounding soil provide insulation from extreme cold.

Nymphs start to feed within a day of hatching, usually on the same plants that they will feed on as adults. These small nymphs are most vulnerable to weather, disease, predators and parasites.

They grow through five nymphal instars, shedding their exoskeleton each time, and become adults in 40 to 55 days after hatching.

Rangeland and pasture damage

Grasshoppers compete for forage with cattle. If enough grasshoppers are present, they can reduce the quality and quantity of forage produced.

This can affect the rancher’s ability to use the pasture effectively for grazing. Grasshoppers consume up to 50 percent of their bodyweight every day in forage.

Cattle consume abut 1.5 percent to 2.5 percent of their bodyweight in forage, so pound for pound, a grasshopper will eat 12 to 20 times as much plant material as a steer.

Another way to look at it is that 30 pounds of grasshoppers will eat as much as a 600-pound steer. In addition, some grasshoppers feed on the most desirable forage plants in the rangeland, leaving the less desirable plants.

Population assessment

Grasshopper populations can be assessed through several methods. The square yard method requires the surveyor to walk in a straight line across an area, visually delineate a square yard area about 9 to 12 feet in front of the surveyor and simply count the number of grasshoppers seen jumping out of the space.

About 30 samples should be taken, each spaced about 75 feet apart. Take an average of the counts to determine grasshopper population densities.

With the square foot method, the surveyor counts grasshoppers from 18 different “square foot” areas in much the same manner as is done with the square yard method.

After 18 samples have been taken, divide the total grasshoppers counted by two to come up with an average number of grasshoppers per square yard.

If the species of grasshoppers causing damage need to be identified, it may be useful to obtain a sweep net and sample several different one-square-yard areas.

Place the collected grasshoppers in a container to be identified by someone familiar with grasshopper identification.

Management options

Ranchers may find it hard to judge whether grasshopper control is economically warranted.

Since grasshoppers compete with cattle for forage, they can reduce the “quality” of rangeland in much the same way that cattle can through overgrazing.

On the other hand, grasshoppers serve as a valuable food source for wildlife, especially game birds, a fact that must be considered when making grasshopper management decisions.

Ranchers can minimize grasshopper damage by properly managing their range according to accepted practices. Healthy, desirable rangeland is less prone to long-term damage.

Grasshopper control in rangeland is probably never justified until numbers exceed 12 per square yard. Even then, the threshold for treating varies with the cost of the insecticide treatment, the projected forage yield and value of the area.

The best time to control grasshoppers is from mid-May through about July 1, while they are immature. Grasshopper control is more effective if practiced over large areas because grasshopper adults can fly for miles to search for suitable food.

If infestations are detected early, an insecticide application in the egg-hatching areas (fence rows, grassy terraces and roadside ditches) can effectively reduce numbers so that chemical control may not be needed later.There are two options a producer might consider:

• Spot treatments in hatching areas or border sprays

Grasshopper eggs are often deposited in concentrated egg-laying sites, such as pastures, ditches and field margins that were not tilled.

Grasshopper nymphs tend to remain concentrated in their hatching areas for some time after they emerge, so applying an approved insecticide as a spot treatment in those areas can effectively reduce grasshopper numbers in a local area.

• Broadcast applications

A producer can apply an approved insecticide as a spray or bait in broadcast application to control grasshoppers. However, such an application should be economically justified beforehand, because it is expensive.

It may be justified in improved pasture, where the producer is harvesting hay as a cash crop. Consider the cost of supplying hay versus spraying before making such a decision to treat in a grazing situation.

Alfalfa damage assessment and management options

Although grasshoppers may defoliate alfalfa in areas adjacent to field borders, they pose a more serious threat in fields used for seed production.

In these areas, grasshoppers will preferably feed on fruiting structures when the crop is in bloom, causing heavy losses of the seed crop along the field margins.

Similarly, if grasshopper populations remain high into the fall, seedling stands of recently planted alfalfa can be devastated.

Although many chemical options are available for grasshopper control in alfalfa, the greatest impact can be realized by targeting populations in areas adjacent to alfalfa fields before grasshoppers reach maturity in June.

Regardless of the age of an alfalfa stand, this management approach will help in avoiding applications targeted at adult grasshoppers, which are difficult to control.

In the case of fields used for seed production, early management in border areas will prevent serious losses of seed and preserve beneficial organisms and pollinators.

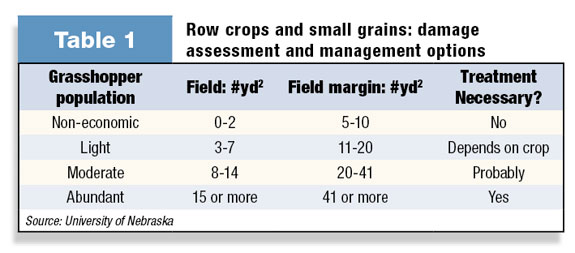

Row crops and small grains damage assessment and management options

Grasshoppers can become a problem in row crops and small grains. They tend to injure corn, soybean and wheat. Corn and soybeans are likely to suffer defoliation in late summer and fall, including damage to the ear of corn or the soybean seed pod.

Winter wheat is more vulnerable to damage in the fall, which can result in stand loss. More often than not, damage occurs in the first 50 to 100 feet on the field border as grasshoppers move in from roadside ditches.

There are no fixed thresholds for control, but Table 1 shows some general guidelines to consider.

References omitted due to space but are available upon request. Click here to email an editor.

—Excerpts from Oklahoma State University Extension newsletter