As a result, many recommendations are made without the necessary rigor to support or challenge the arising practices.

One of these recommendations is to feed large quantities of pellet in the automated milking system to stimulate voluntary visits and promote a precision feeding opportunity. Recent research has demonstrated four notable concerns associated with feeding large quantities of pellet in the automated milking system. The concerns and their implications are listed below.

1. Will increasing automated milking systems’ pellet provision improve voluntary attendance, milk yield or milk component yield?

Two different dietary strategies can be used when altering the amount of pellet. The first approach is to feed diets equal in nutrient supply when considering the combined contribution of the pellet and the partial mixed ration (PMR). This can be achieved by varying the amount of pellet and the amount of concentrate in the PMR. This approach is relevant for producers evaluating the PMR energy density and the quantity of pellet they would like to offer.

Studies have been conducted in both free-flow traffic and guided-traffic barns, with the pellet quantity ranging from about 1 to 17.5 pounds. Interestingly, these studies have consistently demonstrated the quantity of concentrate offered in the automated milking system (when the total diet provides the same nutrient supply) does not affect voluntary visits to the automated milking system, milk yield or milk component yield. Perhaps it is not that surprising milk yield is not increased when the dietary nutrient density is not altered.

In the second dietary strategy, the amount of pellet offered in the automated milking system is increased without changing the PMR. In this scenario, the increase in pellet is intended to increase the nutrient density of the diet – a strategy that could be used for precision feeding. In a survey-based study (93 percent free-flow herds) in the U.S., results demonstrated greater quantities of concentrate offered in the automated milking system decreased milk production; however, again, information on the PMR was not available.

Another study compared 4.4 and 13.2 pounds of pellet in the automated milking system and reported slight increases for milk yield and milk protein yield for the 13.2-pound treatment, suggesting there may be some potential to increase nutrient supply by altering pellet allocation.

However, the same yield responses were also observed in that study when the PMR contained a greater nutrient density. The lack of a strong production response when the allocation of the pellet increases is likely due to the reduction in PMR intake that occurs as pellet intake increases. This issue will be addressed in point 4.

2. The amount of pellet programmed in the software does not equal the quantity of pellet consumed.

The quantity of pellet delivered in the automated milking system may be constrained by a number of factors including, but not limited to, the number of visits to the automated milking system, the programmed maximum meal size, the amount of pellet offered the previous day and potential for carry-over, and other manufacturer-specific factors.

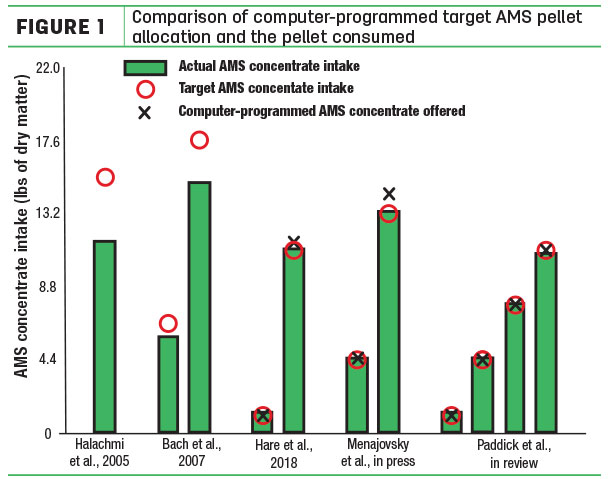

Cows may also not consume all pellet delivered. Assuming cows do consume the pellet offered, there can be a discrepancy between the quantity programmed in the computer and what cows are delivered. In Figure 1, we have summarized studies that have provided pellet in the automated milking system and show the delivered quantity and the quantity programmed in the software are not equal unless low quantities of pellet are targeted.

In fact, the difference between the programmed value and the delivered value increases as the amount of pellet desired to be offered increases. The difference between the amount programmed in the software and the amount delivered has important practical implications as, if no action is taken, the diet cows consume does not equal the diet formulated – a concept that does not align with precision feeding.

Two approaches are available to address this challenge. One approach is to increase the programmed pellet allocation such that the amount delivered equals the quantity specified during diet formulation. However, this approach takes considerable monitoring and adjustment for each quantity of pellet offered. This can be difficult to achieve when using feed tables.

The other option is to re-formulate the diet to account for the average pellet allocation. The question that remains is whether the average concentrate offered allows for precision management. Given the difference between the programmed amount of pellet and delivered amount increase with increasing pellet allocation, and that the amount of pellet cows refuse also increases, the ability to impose diets that differ substantially in nutrient density may be more of a theory than a current possibility.

3. High automated milking system concentrate allocation increases the variability in daily concentrate intake.

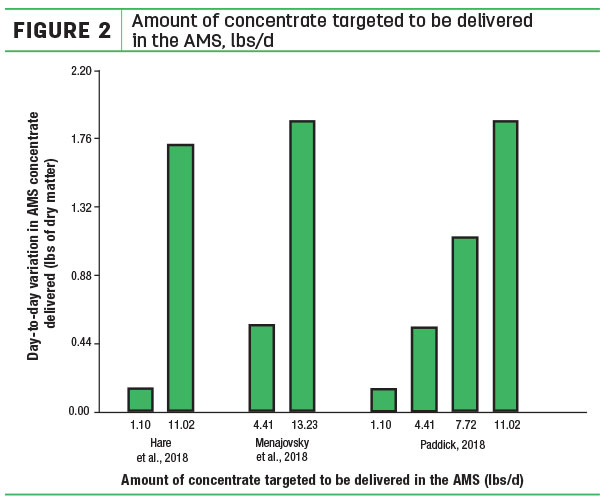

In addition to the greater difference between the computer-programmed quantity to be offered and the quantity actually delivered, increasing the pellet allocation increases the variability in pellet intake for individual cows among days. To our knowledge, there are no built-in reports available that allow producers to evaluate how consistently or inconsistently cows are achieving their daily concentrate allocation.

We have found when comparing low (less than 4.4 pounds per day) versus high (11 to 13.2 pounds per day) pellet allocations, greater day-to-day variation was observed with high quantities. In fact, when offering 11 to 13.2 pounds per cow per day (dry matter basis), the daily difference that could be expected in concentrate intake was 1.7 to 2 pounds per day (Figure 2).

To simplify the latter example, when 11 pounds of pellet dry matter was offered in the automated milking system, intake of pellet is expected to range between 9.3 and 12.8 pounds per day. Thus, dietary consistency and nutrient intake predictability are reduced with greater pellet allocations. Interestingly, increasing the energy density of the PMR does not seem to affect variability in pellet intake or PMR intake across days.

4. The automated milking system concentrate allocation cannot be considered without the PMR.

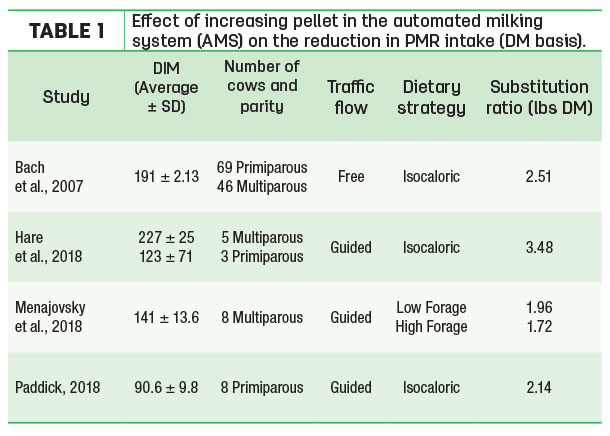

Feeding programs for cows milked with an automated milking system must consider both the pellet and the PMR. Studies that have evaluated both PMR intake and pellet intake have demonstrated as the quantity of pellet increases, the intake of PMR is reduced, resulting in a “substitution effect.”

Substitution effects are well recognized and have been evaluated under grazing scenarios for many years. With automated milking systems, for every 1-pound increase in pellet (dry matter basis), the intake of PMR (dry matter basis) has been reduced by as little as 0.8 pounds or as much as 1.6 pounds.

A major challenge is: The substitution effect is inconsistent (Table 1). Given differences in study design, it is not currently possible to predict the substitution effect.

The substitution effect may be the reason explaining why the increase in milk yield is small or not observed as the pellet allocation increases. For example, if PMR intake (dry matter basis) decreases to a greater extent than the pellet intake increases, the potential to increase energy intake is marginalized.

Moreover, the substitution effect can unpredictably affect diet composition. In one study, increasing the pellet allocation decreased dry matter, neutral detergent fiber (NDF) and acid detergent fiber (ADF) digestibility, thereby providing another reason why increasing the pellet might not increase milk yield to the extent predicted.

The concentrate allocation (and arising changes in the PMR) also influences PMR sorting behaviour, PMR meal duration and PMR eating rate. Thus, consideration of both the concentrate intake and PMR are necessary to meet nutrient requirements. Unfortunately, research is surprisingly limited in this area.

While the research findings summarized above do not allow for a recommendation on the optimal range for pellet allocation and the associated PMR composition, they do indicate increasing the pellet allocation may not prove to be as successful as intended.

In fact, the available research findings challenge the concept of increasing the allocation of a single pellet as a strategy to enable precision feeding. Certainly, more research is needed in this area, but caution should be applied when targeting high quantities of pellet in the automated milking system. ![]()

Greg Penner is also with the University of Saskatchewan Department of Animal and Poultry Science.

References omitted but are available upon request. Click here to email an editor.

Keshia Paddick is with the department of animal and poultry science at the University of Saskatchewan.