Lameness is a costly issue for dairy farms, with an average prevalence of 25% of dairy cows on U.S. dairies experiencing lameness. Much of these costs are associated with milk loss and can add up to $200 to $500 per case.

In New York, we wanted to dig deeper into the economics of lameness by forming a discussion group looking at prevalence of lameness in addition to the costs associated with prevention and treatment. Dairy farmers we work with have repeatedly told us they like learning from their peers and enjoy hearing how other farms are working through different issues. This group utilized an initial on-farm lameness assessment using a three-point scale (1: sound, 2: mildly lame, 3: severely lame). Each of the nine participating farms also tracked three months of data related to lameness management and treatment, including treatment, labor, footbath use, and veterinary and supply costs. Farm size ranged from 90 to 750 lactating cows from northern and central New York. Each farm also received a second assessment at the end of the project, four months after the first. Farms were provided with an individual report on lameness prevalence and economic data in comparison to the other eight herds. A group meeting was held to go over data in detail and provide an opportunity for farmers to ask other members questions on farm practices.

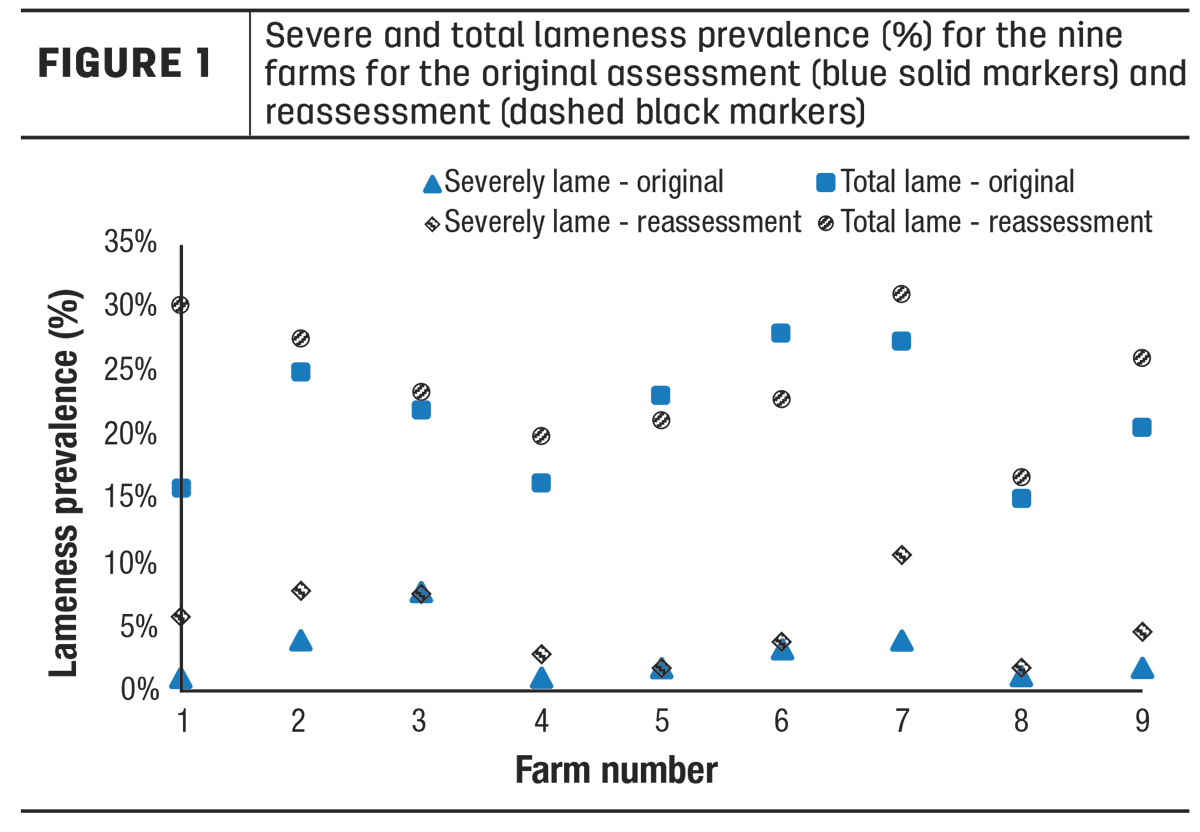

The lameness data in this project were similar to previous studies in New York and across the U.S. For the initial assessment, the average overall lameness prevalence for the nine farms was 21.8%, with 19.1% mild and 2.8% severe (Figure 1).

Lameness prevalence on individual farms ranged from 15.1% to 28%, with severe ranging from 1.1% to 7.8%. Lameness during the reassessment averaged 22.4%, with 18.3% mild and 4.1% severe. Again, there was a wide range in lameness between farms, from 16.7% to 31.1% overall and 1.8% to 10.7% severe. Overall, lameness increased slightly during the reassessment due to an increase in severe cases, but a few individual farms showed improvements during the course of the study.

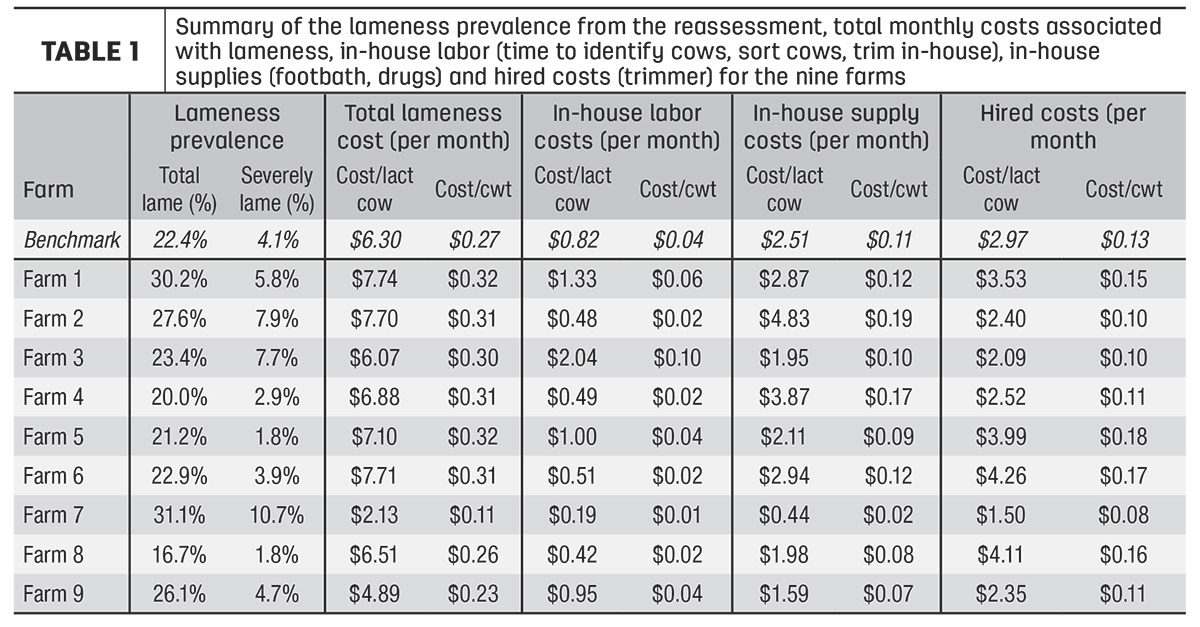

Economic data were broken down into per-month costs, on both a per-milking cow basis as well as a per-hundredweight (cwt) basis. Our nine-herd benchmark averaged $6.30 per cow for total lameness cost and 27 cents per cwt, ranging from $2.13 to $7.74 per cow per month and 11 cents to 32 cents per cwt per month. Interestingly, six of the nine herds showed a monthly cost of 30 cents to 32 cents per cwt, even with a large range of lameness on farm. The means in how this value was achieved, however, differed greatly. Some farms utilized in-house trimming versus hiring a trimmer, making their hired costs look extremely low, but in the end, costs on a per-cwt basis remained very similar to farms that hired trimming.

Table 1 shows a breakdown of these costs by in-house labor costs (identifying lame cows, sorting cows for trimming, trimming in-house, running footbaths), in-house supply costs (footbath supplies, medicine, trimming supplies) and hired costs (hired trimmer).

When asked what they found most valuable about the project, participating farms said the locomotion scoring and having their cows scored multiple times to show where they are actually at. Additionally, they liked the economic comparison, the discussion between other farmers, and being able to compare themselves to other farms and their lameness scores, as well as associated facility and management factors.

The data and discussion helped spark some change on the participating farms, particularly with footbath protocols and management. Some farms mentioned they switched to a whole new product or just tweaked their existing schedule (when and how often), or the concentration and amount used. A few farms made other changes to management and facilities to improve lameness and cow comfort. One farm started more aggressively culling severely lame cows, reduced stall stocking density and put in new rubber flooring in some areas. While improvements in lameness can take months to become apparent, this farm said they are already “pleasantly surprised” after focusing on addressing lameness, and they said they feel it is working. Further changes include a farm installing new rubber in a drover lane and the holding area, and another addressing fly pressure to reduce summertime bunching and increase lying time.

Given the short time frame of the project, some farms had not yet implemented changes, but they indicated they were planning to. For example, one farm wanted to increase alley scraping frequency from twice per day to three times per day, make the stalls larger to increase use and reduce perching, and consider a new footbath product. Another farm wanted to focus on bedding to improve cow comfort, and another wanted to switch to a different footbath product and resurface some old laneways. To address the issue of seasonality possibly impacting the reassessment data to a degree, some farms also asked for follow-up assessments to continue to monitor lameness prevalence throughout the year.

It is important to consider a few factors about this study. We utilized a small sample size, only nine farms, as well as only two assessments four months apart, with the second assessment occurring in early fall. Even though our lameness benchmark reassessment data were worse on average, it should be noted that the seasonality of lameness can be a real influence. In addition, our dataset was limited to three months of information, and we did not gather any milk loss or losses related to culling. Lameness is indeed a costly issue for dairies, and this study was intended to capture information on factors the dairy pays great attention to – footbaths, trimming and supplies.

Utilizing a discussion group format is an effective way to gather information on a specific topic to elicit dialogue around a costly issue like lameness. Data compiled not only gives information on lameness prevalence but also on economic factors related to lameness; members in the discussion group were able to use these numbers to share ideas and offer suggestions for others to implement.

The exciting thing with this study is that there was not just one strategy employed by every farm; each farm in the group utilized a different approach to managing lameness and often had a different focus. Some had adequate labor and wanted to keep trimming in-house to keep hired costs down. Others focused on improving lameness through preventative means such as improving flooring and adding rubber.

With data in hand, conversations during a group meeting are effective at eliciting change – farmers love to hear real stories from other farmers.