For many dairy farmers, farming is widely viewed as a “way of life” rather than as a business. The Internal Revenue Service (IRS) considers an activity a trade or business if it is conducted with a profit motive. Profit is defined as income or receipts greater than expenses, where expenses include depreciation of capital assets. Just a note, this determination of “profit motive” does not require that a profit be generated, only that there is a motive for making a profit in conducting the activity. For tax purposes, generally all individuals, partnerships or corporations that cultivate, operate or manage farms for a gain or profit – either as owners or tenants – are farmers. Farming activity includes livestock, dairy, poultry, fish, fruit and truck farms.

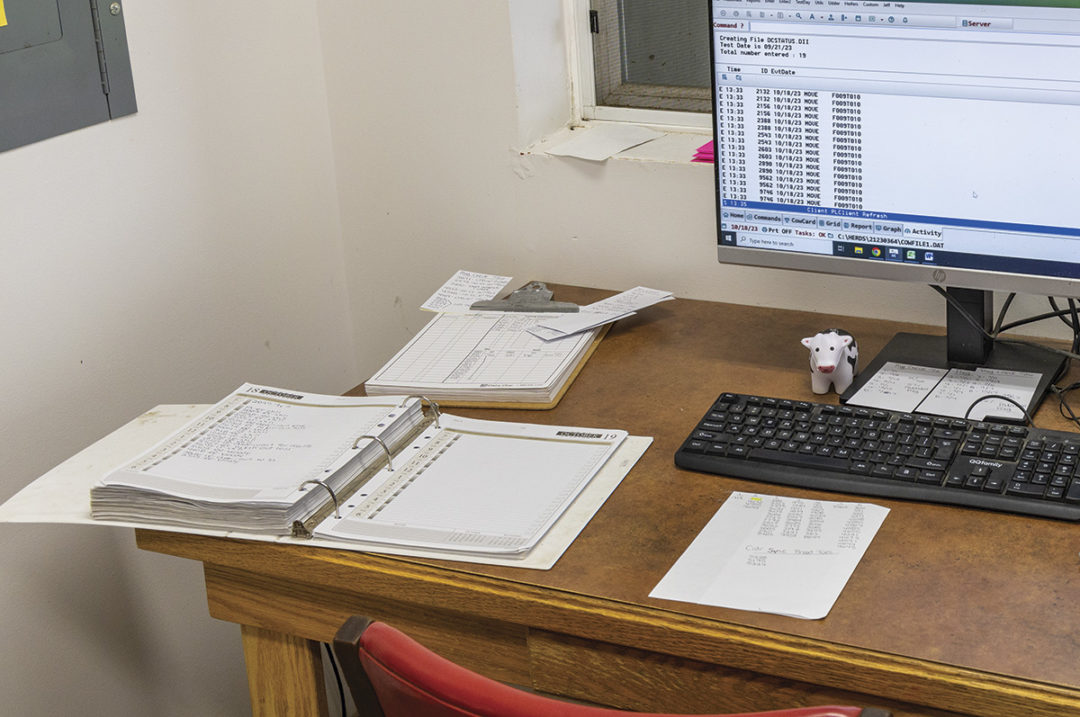

Farming is a complex business which demands accurate records and careful financial management. Both financial and production records are required to provide information the farmer needs to make critical risk management decisions. Recordkeeping begins with collecting and organizing of the farm business’s production (physical) and financial (income/expense) information.

Physical records

Production or physical records may be related to:

- Livestock: Identification; weights, date of birth, pregnancy rate, calving rate, death loss rate, average weaning weight, average daily gain

- Crop: Yields, inputs (fertilizer, seed), pesticide application, irrigation, planting and harvest dates

- Labor: Paid and unpaid

- Weather: Precipitation, wind, storm events (hail, snow)

Financial records

Financial records that may be kept include:

- Income and expense receipts

- Invoices sent to and from customers

- Checks and bank statements

Methods of recordkeeping

Records may need to be provided to government agencies, lenders, insurance companies, safe handling practices, organic production, etc. One of the most important decisions is deciding how to track production and financial records.

- Paper: “Shoebox” method, pen and paper or notebook, ledger book specific to production and/or financial records. This method requires more time, with potential user errors, but is favorable to farmers not familiar with computers. Minor costs are associated with this method.

- Electronic: Spreadsheet (like Microsoft Excel, Google Sheets, etc.), business financial software packages (such as QuickBooks or Quicken) or more farm-specific financial software packages (like CenterPoint, Farm Biz, PCMars, Ultra Farm Accounting and others). The program may complete the financial calculations; however, the farmer must have a basic knowledge of computers, time to learn the software, design the form and enter the receipts correctly. There may be varying costs associated with an electronic method.

- Outsourcing: Hiring a professional for recordkeeping. Expect higher costs associated with this method.

Record retention

Regardless of the method a dairy farmer uses, they likely have a lot of documents in storage. Unfortunately, there is not a steadfast retention rule regarding all these records. Several federal agencies have document retention requirements, including the IRS and those related to hiring employees (OSHA, FLSA, etc.). It is essential to understand which categories apply to know what documents to keep.

Document retention guidelines typically require businesses to store records for one, three or seven years. In some cases, farmers may need to keep the records forever.

- Legal documents, such as business formation records, deeds, property appraisals, bill of sale documents, etc., should be kept indefinitely.

- According to the IRS, tax returns should be kept for three to seven years, depending on the situation. The statute of limitations period for income tax returns is generally three years. It is six years if there is a substantial understatement of gross income. A good rule of thumb is to add a year to the statute of limitations period. Using this approach, farmers should keep most of their income tax records for a minimum of four years, but it may be more prudent to retain them for seven years.

- Retain all farm business financial records applicable to income taxes, including depreciation schedules and year-end financial statements, for at least seven years. A certified public accountant (CPA) may recommend keeping accounting records indefinitely.

- All business banking, credit card and investment statements, as well as canceled checks, should be kept for seven years, possibly longer, depending on business or tax circumstances.

- Keep all permits, licenses and insurance policy documents until a replacement is received for expired ones.

- The Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA) requires employers to keep payroll records “for at least three years.” Refer to the federal record retention guidelines for a precise breakdown of requirements for personnel records. For instance, documents relating to exposure from harmful agents must be kept for 30 years after employment ends. In contrast, farmers should keep OSHA accident forms for five years after the incident.

- Keep job advertisements, applications and resumes on file for at least one year.

Summary

Recordkeeping is best kept simple. There is no “best” record-keeping system for all situations. If the record-keeping method is too complicated, the farmer may be more likely to make mistakes or avoid recordkeeping all altogether. Records should provide essential information on a timely basis. Both financial and production records need to be collected and organized to generate management reports for farm business decision-making. Establishing a record retention policy ensures a farmer can comply with record-keeping standards.

This article is provided for information purposes only. Readers should consult their own professional advisers for specific advice tailored to their needs. Information contained in this article may be subject to change without notice.