Dairies that have mastered the art of the transition period have a handful of things in common – and surprisingly, good nutrition is not the only one. Dr. Ken Nordlund from the University of Wisconsin – Madison shared his top five findings for transition cow success during the Minnesota Dairy Health Conference held in Minneapolis, Minnesota, May 20-22.

“We had been overemphasizing ration formulation to fix transition problems,” he stated. “We had forgotten about the space and comfort of the cow.”

Nordlund based his findings on transition cow index (TCI) scores because this tool measures transition cow health and herd management specific to commercial dairies. It is a patented index that predicts a first test-date milk yield for each cow in her second or greater lactation based upon that cow’s previous performance and then compares it to her actual first test-date milk yield in the new lactation.

After evaluating extensive data from 50 Midwestern freestall and 22 Western open-lot dairies, five factors emerged as associated with higher herd TCI scores.

1. Sufficient bunk space

2. Comfortable, appropriately sized stalls

3. Soft-bedded stall surfaces

4. Minimized social stress

5. Effective fresh cow screening programs

“These appear to be bigger factors than ration formulation,” Nordlund added. “We can take a great ration and put it in a pen with undersized stalls, a hard surface, a lot of pen moves at the wrong time and with a herdsperson who has a hard time distinguishing life from death, and a great ration will not produce a successful program.”

Sufficient bunk space

The most important factor in determining transition cow performance is sufficient space at the feedbunk, according to Nordlund. Ideally, all cows should be eating simultaneously to maximize the 90-minute period following fresh feed delivery and milking.

“Feeding space per cow was the single-most robust predictor of TCI,” he said.

Calculate space per cow based on the length of the bunk, not the number of headlocks in a pen. Nordlund recommends 30 inches of bunk space per adult Holstein cow in a prefresh and postfresh pen with headlocks or vertical dividers. Post-and-rail feeders require additional space.

Though pen numbers constantly flux as cows move in and out of close-up and fresh pens on a daily or weekly basis, facilities should be built to accommodate the calving surges.

He recommends sizing these pens at 140 percent of the average number of calvings to avoid overstocking. While this may seem overbuilt, Nordlund emphasized that investing in ample space will provide a residual benefit.

“Each prefresh stall is a factor in starting somewhere between 15 and 17 lactations per year. If there is a benefit here, the multiplier effect is huge,” he said.

Comfortable, appropriately sized stalls

Stall size was also identified as a risk factor when it comes to transition cow success. Pregnant cows simply need more room to lie, rise and rest.

As cow body size increases, the stall dimensions of the past are no longer ideal for prepartum cows. The average Midwestern freestall built over the last decade measured 45 inches wide and 66 inches long from the rear curb to the brisket locator.

According to Nordlund, that sizing may fit a first-lactation Holstein, but a mature cow needs a 50-inch wide by 70-inch long stall to truly be comfortable. A pregnant Jersey requires a stall that is 45 inches wide by 63 inches long.

How does a bigger stall for transition cows translate into a bigger profit? Nordlund noted one dairy that remodeled stalls to the recommended length and width. Prior to the remodel, there was a gap in mature equivalent (ME). Though first-lactation cows performed well, older cows showed a 1-ton drop. After the stall expansion, that ME gap disappeared.

On dairies with open lots, cows should be offered 45 square feet of shaded space covering an area with at least 3 inches of loose bedding .

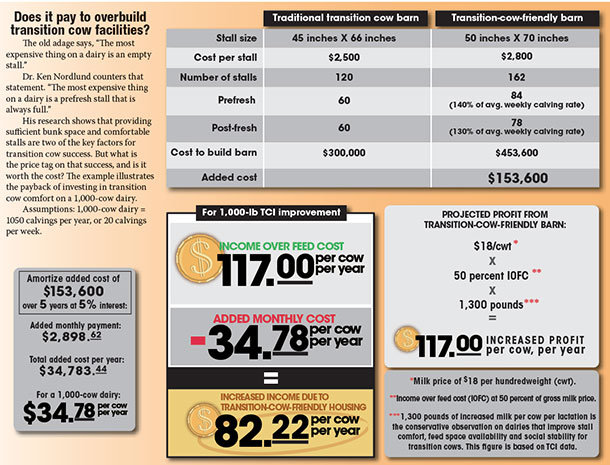

Click here on image above to download a PDF of this image. (PDF, 453K)

Soft-bedded stall surfaces

When it comes to transition cows, what is in the stall counts, too. Deep, loose sand bedding was associated with significant advantages in TCI scores when compared to herds housed on harder surfaces like mattresses.

Nordlund’s research looked at the cows’ time budgets and locomotion scores. He observed that while transition cows tend to have slightly higher locomotion scores, behavior did not change for cows kept in sand-bedded stalls.

Those on mattresses, however, spent more time standing in the stall and less time eating. He noted as much as an 8-pound production difference between the two stall surfaces.

When mattresses are covered with a bedding material like wood shavings, the surface is improved, but a hard base surface such as concrete, even with bedding, is a transition risk factor.

Minimized social stress

For transition cows, establishing social order brings on additional stress. That said, the fewer pen moves, the better.

As cows move into new social groups, the first two days are often filled with physical interactions with other animals as social order is established. After that, the group stabilizes, assuming no other new cows are introduced.

An approach to minimizing social stress is an all-in strategy where cows with calving dates within a seven-day to 14-day window are kept in a stable group. The group can be assembled three weeks prior to the expected calving date or at dry-off. This approach cuts down on stressful social interactions during the weeks prior to calving.

Nordlund cautioned against daily pen moves because of the high level of social turmoil. When this management style is practiced, Nordlund suggested minimizing the time prepartum cows spend in these pens to no longer than 48 hours.

Data from UW reveals a dramatic increase in fresh cow diseases such as ketosis and displaced abomasum, along with early lactation culling, for cows that stay three to 10 days in daily entry group pens.

“Just in time” calving has become common practice on commercial dairies. Waiting to move the cow to the calving pen until the feet or head of the calf is showing effectively minimizes time spent in high-turmoil pens. However, this system poses some challenges from a management standpoint.

Not only does it require 24-hour labor, but workers must be monitored to ensure they are not moving cows into the calving pen too soon. Research shows that the stillbirth rate increases by 2.5 times if cows are moved when only mucus – not the calf – is showing.

Effective fresh cow screening programs

Picking up on early signs and symptoms of fresh cow disease can make or break a cow’s lactation. Doing so requires having both the right people and the right process in place, which may be easier said than done.

“The skill of the screening personnel is probably the most variable item on a dairy today,” Nordlund stated.

Among the best transition cow programs studied, he found a few practices in common. Astute herd managers followed cows to and from the milking parlor to observe behavior, and they palpated udders in the parlor to check for fullness.

Cows returned from the parlor to fresh feed at the bunk, which gave the herdsperson another opportunity to watch behaviors that may indicate concern, such as going directly to a stall instead of eating. This combination of attitude and appetite evaluation was used as a guideline to determine which cows needed special attention.

Other transition cow programs included checking daily rectal temperatures and monitoring milk production.

If cows are locked up upon returning to feed, be sure to release them within one hour. Prolonged lock-ups are related to decreased lying time and increased stress. PD

Peggy Coffeen

Editor

Progressive Dairyman