The author who brought us Black Swans (unexpected events with big consequences) is back, and he’s raising a very thought-provoking question every dairy producer should ask in this era of market volatility: Is your dairy “fragile” or “antifragile?” The author is Nassim Nicholas Taleb, professor of risk engineering at New York University’s Polytechnic Institute. His new book, Antifragile: Things That Gain from Disorder, will make you think about how to strengthen your business to survive ups and downs.

And strengthen we must. Stories about uncertainty abound: Is the reliable three-year milk cycle dead? Will drought send feed to $12 this year? Will a bumper crop keep feed prices lower? Will there be any productive debate over the Farm Bill and the milk pricing system? When will inflation strike, and what will that do to land prices?

Click here to see a related video from Scott Stewart, where he discusses dairy markets.

Taleb calls on businesses and governments to develop antifragility so that they can thrive and improve in the face of disorder. “By grasping the mechanisms of antifragility,” he writes, “we can make better decisions without the illusion of being able to predict the next big thing. We can navigate situations in which the unknown predominates and our understanding is limited.”

As a business owner, that’s where I want to be. I want to be strong enough to survive the economic uncertainty, government regulations, financial and natural disasters that seem to come around quite regularly these days. Before we discuss how to do that, let’s take a look at how Taleb defines “fragile” and “antifragile.”

How do we get fragile?

Taleb gives many examples of ways that things become fragile, despite our best intentions: “Deprive your bones of stress and they become brittle,” is one example he gives. “Walking on smooth surfaces with ‘comfortable’ shoes injures our feet and back musculature” is another example.

In nature, we see many examples, such as flammable material accumulating on the forest floor: If we do all we can to eliminate stress on the environment and prevent forest fires, the intensity of the eventual, inevitable forest fire is huge and tragic.

It turns out that in a desperate attempt to correct natural behaviors that cause some level of discomfort, we cause even worse problems and breed mass inefficiencies into our businesses, our bodies or our societies.

Taleb even questions the economic policies that seek to stifle natural fluctuations. What will be the effect of trying to “smooth” things out by injecting cheap money into the U.S. economy? And if we make all this effort to smooth things out, will we have the resources to intervene when it’s really necessary, like after a natural disaster?

To be “antifragile,” according to Taleb, is more than just being sturdy or resilient. It is being able to gain from volatility, variability, stress and disorder. How many dairies can say that? I believe it is the dairies that use the “mechanisms of antifragility” best that can gain from the current volatility and uncertainty.

‘Mechanisms of antifragility’

What are the “mechanisms of antifragility” that Taleb encourages? There are many in his book, and I encourage you to read it to discover all the ways you can manage your dairy to become more antifragile. From where I sit, consistent use of pricing tools helps build antifragility.

We see this all the time as we work with dairy producers and their lenders. After 2009, milk prices came back much faster than the banking system could recover and free up money. Dairies continue to struggle under tight lending requirements regardless of the rebound and retreat of milk prices.

Many of the dairies enjoying good standing with their lenders have managed consistently well through good prices, have taken advantage of pricing opportunities and maintained a healthy balance sheet when prices turned lower.

Some might argue that the ability to “ride out price swings” means you are more agile, and therefore less fragile. For this to be true, your dairy needs to be antifragile in many other ways. I would argue that using a consistent, disciplined approach to the markets gives dairies agility that doesn’t exist in other forms.

Why? Dairies simply do not have the same flexibility to ride through tough times as, say, a manufacturing plant does. With manufacturing, when times are tough, you can sell factories, lay off workers and eliminate facilities that are less efficient to make your operation more lean.

In the dairy business, you can’t just lay cows off. (If you did, you would need to do that counter-cyclically to the markets. You’d have to sell cows when they have a high value. No one does that.)

The alternative is to gain your agility from the markets. When prices are high, sell your milk. When they are low, you’ll usually find opportunities to price your feed.

Agile producers can use a consistent, strategic marketing program to manage the good times so well that they have cash on hand to absorb the shock of the bad times. And so, when it comes to the “mechanisms of antifragility,” the markets truly are an important tool for dairy operations.

Despite the growing use of these tools, there is no guarantee they will make a business antifragile.

They have to be used correctly. One trend we’re seeing since 2009 is producers wanting to lock in a reasonable margin wherever they can.

This approach, in our opinion, actually puts a dairy in a fragile position. It is trying to remove all risk, and it can leave tons of opportunity on the table.

If you buy into the idea that a little bit of profit is good enough, you’ll find yourself closer to the average of all producers, instead of well above the breakeven or average line. And average simply won’t be good enough in the long run.

That’s a significant point to grasp. When you are in the business of producing commodities, prices will always go through boom-and-bust cycles and settle near the average breakeven point for all producers.

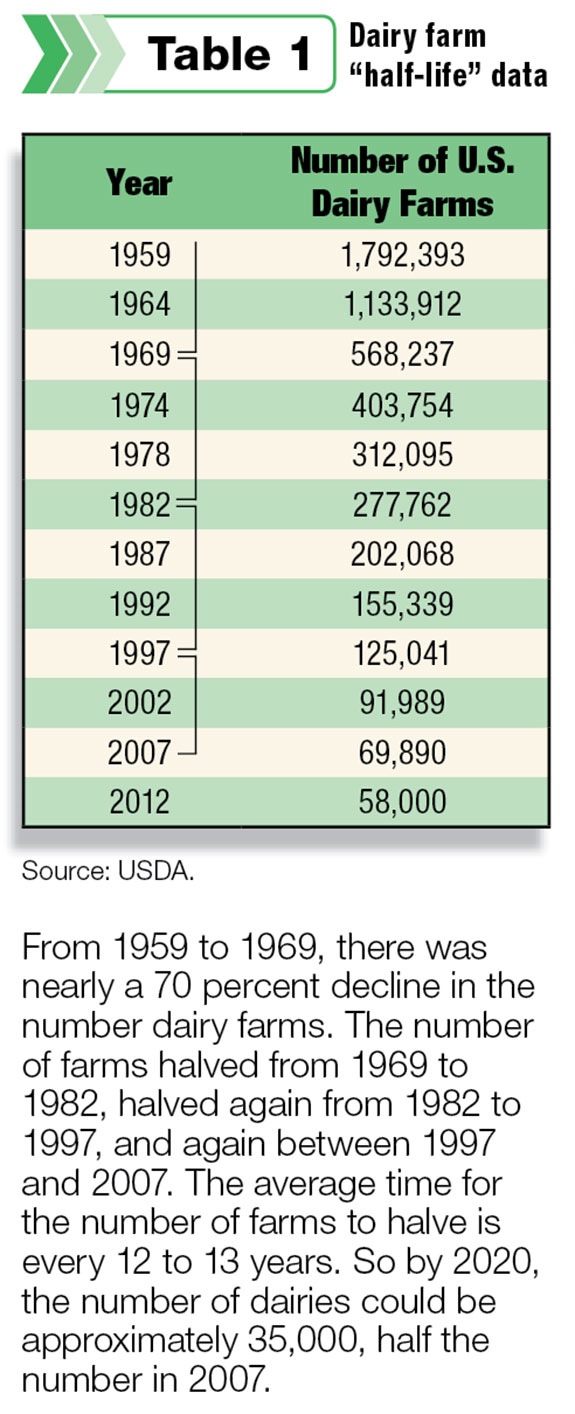

Those above breakeven survive; those below will find something else to do. According to our review of USDA data for dairy farms since 1959, about half of U.S. dairy farms exit the business every 12.5 years on average (see Table 1 ).

This means that by the year 2020, the number of U.S. dairies could be approximately 35,000 – half the number in 2007.

The dairies that can consistently capture more than average in the boom-and-bust cycles will increase their measure of antifragility.

Get stronger

“Things that are antifragile only grow and improve under adversity,” Taleb writes. That’s the category I want my business to be in, and we want that for our clients, too.

No matter how high or how low prices for milk or feed go, or if the Black Swan of another drought swoops in, we will be looking for opportunity.

We can view ourselves as victims or take the view that with stress comes strength.

Even the 2013 Super Bowl saw a Black Swan swoop in when the power went out in the Superdome. Did anyone have contingency plans for that unexpected event? Yet you can be sure that the next Super Bowl hosts will be prepared and stronger for it.

Farming is, by nature, a risky business. If you take all the risk out of it, you take out all the opportunity as well. The key is using every available tool to become “antifragile” – above average and able to emerge from price swings as a stronger business. PD

Antifragile: Things That Gain from Disorder by Nassim Nicholas Taleb was published by Random House in November 2012. Quotes from this article were taken from Taleb’s own summary of his book published in the Wall Street Journal on November 17, 2012.

Disclaimer: Futures trading involves risk of loss and should be carefully considered before investing. Past performance may not be indicative of future results. The data herein is believed to be accurate and cannot be guaranteed.