The ability to harvest moist forage as haylage gives forage producers in the humid regions of the U.S. many advantages, including timely harvest, higher nutritive quality and less weathering loss compared to hay systems.

The baleage system allows producers to utilize commonly available forage equipment (mowers, rakes, balers) rather than requiring choppers and silo structures or bags. Making high-quality baleage requires timely access to bale wrappers. To make high-quality baleage, producers should:

- Cut at the proper stage of maturity. Good silage requires quick fermentation of soluble sugars which produces volatile fatty acids (VFA) and lowers pH. The low pH in baleage is what keeps the forage stable in the bale and prevents excessive heating when fed.

- Bale when the wilted forage is between 40% and 65% moisture content (MC).

- Bales should be as tight as possible to help exclude oxygen and accelerate the ensiling process.

- Wrap bales within 24 hours – and ideally the same day.

- Wrap bales with a minimum of four and ideally six to eight layers of UV-stabilized, stretch-wrap plastic.

- Periodically check the wrapped bales and plug any holes present.

- Feed all baleage within 12 months of wrapping.

Inline bale wrappers speed up the baleage operation and save plastic over implements that wrap bales individually. The popularity and expanding availability of inline bale wrappers has resulted in greater application of the technology among producers. Most producers have had excellent results in making and feeding, and even selling baleage.

However, some producers have had animal performance problems and even deaths from feeding baleage. In nearly all cases, feeding problems with baleage are caused by poor quality arising from excessive moisture, inadequate or punctured plastic wrap. These problem instances are few but are often cited as a barrier for adoption of the technology.

To better understand the haylage system and, if possible, to predict when problems will occur with baleage, a project was initiated in Kentucky across the 2017 and 2018 growing season to assess a wide variety of farmer-produced baleage. In all, 44 samples were collected and analyzed for forage quality and extent of fermentation (VFA production). Samples included soybeans, small grains, grasses, grass-legume and alfalfa. Harvest dates ranged from late spring to late November.

Results

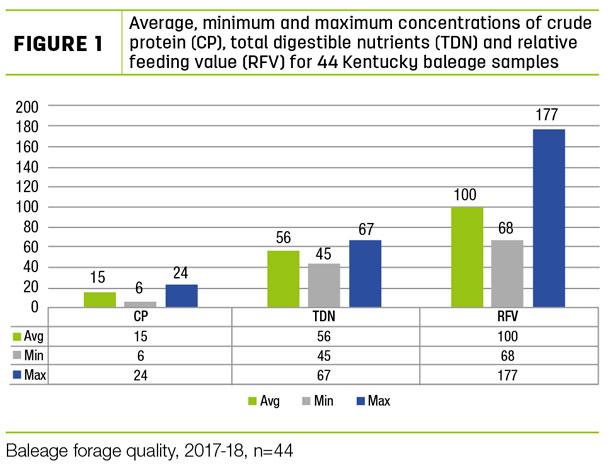

All but one lot of haylage had good visual and odor characteristics. Producers report no feeding issues to date. One problematic sample contained high levels of butyric acid, and the producer was advised that it could be a problem. Forage nutritive value was high, with crude protein, total digestible nutrients (TDN) and relative feed value (RFV) averaging 15%, 56% and 100%, respectively (Figure 1).

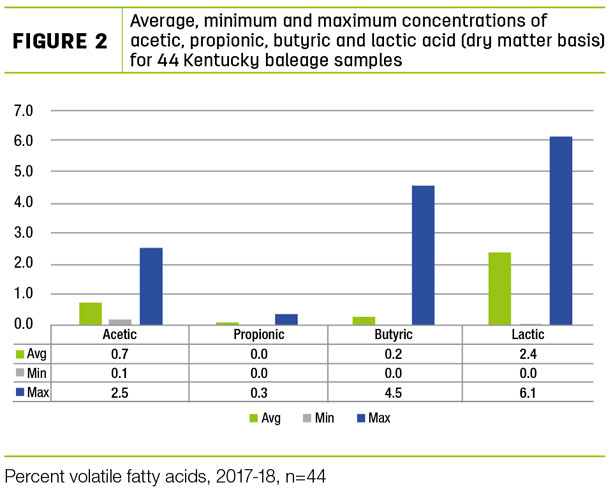

The stability of baled silage can be measured by the total amount of VFA produced as well as the VFA profiles. Volatile fatty acid concentrations varied widely for the baleage in this survey (Figure 2).

Total VFA across all samples averaged 6.0%, which is on the low end of the recommended range of 5.0 to 10.0 (Dairy One Forage Laboratory). The average lactic acid value for these samples was 2.4%, slightly below the recommended value of 3%.

Discussion

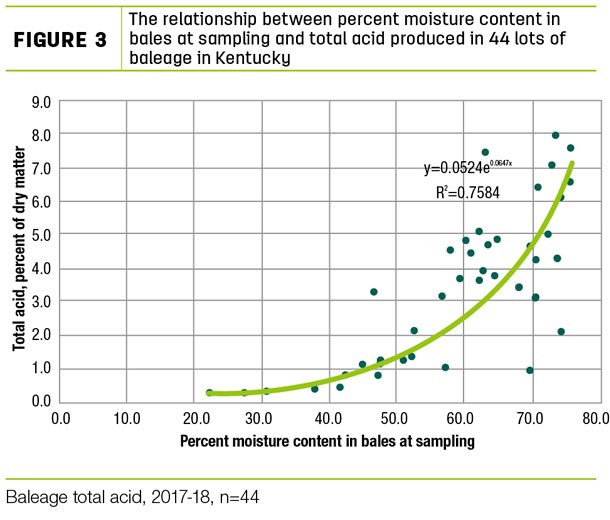

Moisture content had the greatest impact on total acidity, explaining 76% of the variation (the high-butyric-acid sample was omitted from this analysis) (Figure 3).

In baleage with MC between 40% and 60% (a commonly recommended accepted range), lactic acid concentrations failed to exceed the desired level of 3% in 14 of 16 samples. In this sample set, recommended lactic acid concentrations were met more frequently when MC were between 60% and 75%.

Only one sample had an “off” VFA profile, with a butyric acid content of 4.5%. In good baleage, butyric acid should be less than 0.1%. The average across all samples was just above that value at 0.2%. Fifteen of 44 samples had butyric acid values above 0.1%, but all but one were 0.4% or less. The excessive amount of butyric acid in the off sample was very likely due to high MC (80%).

Conclusion

Baleage can readily produce high-quality forage. In a recent survey of 44 samples in Kentucky, VFA profiles were variable and highly correlated to moisture content. Baling on the wetter end of the recommended range (60% MC or above) produced higher levels of “good” VFA in these samples. Very wet baleage (80%) led to high levels of “off-type” VFA (butyric acid).

Producers can assure themselves of the quality of their baleage by testing their baleage for forage quality, and especially pH and VFA concentrations. To test a lot of baleage, core sample a representative set of bales using a core sampler as one would do with dry hay. Consolidate these cores into a Ziploc freezer bag and keep on ice or frozen. Ship samples in styrofoam containers with freezer packs to the forage lab. Most labs will provide a shipping label for a nominal fee.

Ship the samples on a Monday or Tuesday to decrease the chance samples will sit over a weekend awaiting delivery. Instruct the forage lab that you want a nutritive analysis (NIR or wet chemistry) and a fermentation panel or fermentation analysis (for the VFA concentrations). It is critical the samples be kept in a securely sealed plastic bag and frozen until delivered to the forage laboratory. If there is doubt about the security of moisture seal in the sample bag, use two Ziploc bags. If the sample dries out, all VFA will evaporate.