When did the problem with alfalfa weevil begin?

It all started 2,000 years ago when alfalfa, the first cultivated forage crop, was grown in southwestern Asia. Alfalfa’s productivity and nutritive value as feed for livestock animals earned it the nickname “Queen of Forages,” as its use quickly spread throughout Europe.

Brought to the Americas by Spanish and Portuguese conquistadors, it was grown to some extent in several U.S. states by the late 1800s. The alfalfa weevil is native to Eurasia and North Africa, where it feeds on alfalfa and related native plants but was then introduced into the U.S. at least three separate times. The three introductions are called the western (Salt Lake City, Utah, in 1904), Egyptian (Yuma, Arizona, in 1939) and eastern (Maryland in 1952) races. This introduced pest has now spread throughout the continental U.S. and parts of Mexico and Canada, where it remains the major economic pest of alfalfa.

Life cycle, damage and current management

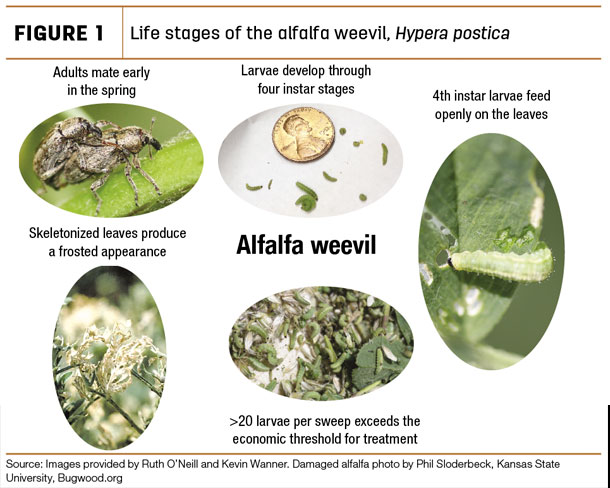

Alfalfa weevils are small quarter-inch-long oval-shaped beetles (insect order coleoptera; family curculionidae) with a large snout. They are light to dark brown in color with a dark brown stripe running down the middle of the back (Figure 1).

As temperatures warm up in the spring, overwintering adults become active, and females lay one to 45 eggs within alfalfa stems. After hatching, the tiny new larvae feed inside the developing leaf buds; the larger larvae feed openly on the leaves and are the most damaging stage.

Small larvae are yellow to pale green, and larger larvae are green with a distinctive thin white line down the center of their back. High populations can consume most of the leaves, giving the field a white frosted appearance and reducing yield.

Alfalfa weevil management recommendations are based on the practice of integrated pest management (IPM): scout and identify the pest, monitor pest numbers, if pest numbers exceed the economic threshold implement available management tools (chemical, cultural, physical and biological tactics) in a coordinated way to reduce pest numbers below the threshold. Larvae can be monitored using a sweep net or by shaking alfalfa stems in a bucket. An average of 20 larvae per sweep or 1.5 to two larvae per alfalfa stem is the threshold that warrants treatment.

A model has been developed to predict larval development and inform scouting efforts based on accumulated average temperatures (degree-days). Once the economic threshold has been met, insecticide sprays can be used to reduce pest numbers and preserve yield or, if the field is within seven to 10 days of being harvested, it can be cut early. While recommendations can vary depending on production region, these have been in place nationally for several decades.

Has the pest status of alfalfa weevil changed?

Producers and county agents in Montana were reporting more frequent damage from alfalfa weevil and the presence of larger larvae earlier in the spring season than normal. With support from a pilot grant from the Western Region IPM Center, we collected larvae from six fields across Montana in 2017; the temperature data accurately predicted their development in only one of the six locations – alfalfa weevil larvae were larger than predicted in the other five locations.

I began calling entomologists in neighboring states and learned producers in the Western region were having similar experiences and also had concerns about weevil resistance to the insecticides. This prompted a symposium to be scheduled at the 2019 Pacific Branch Meeting of the Entomology Society of America in San Diego. This two-hour symposium allows alfalfa weevil researchers to trade notes and observations and report on recent field results.

What is being done to address the problem?

Research trials have begun in several Western states, and the meeting in San Diego will help to coordinate efforts and extend the results regionally.

- The USDA NIFA Alfalfa and Forage Research Program (AFRP) has funded a collaborative project among Montana, Wyoming and Utah to evaluate weevil development in the Intermountain West region and improve the degree-day model. Included is an online database to monitor alfalfa weevil populations in real time across the region, Pestweb.

- Research by the University of Arizona Cooperative Extension is re-evaluating the economic thresholds for treatment in their region.

- The University of Wyoming is assessing the timing of early harvest to best manage alfalfa weevil damage, including effects on forage yield and quality. This research is funded by the Crop Protection and Pest Management (CPPM) section of the USDA Applied Research and Development Program (ARDP).

Research has begun to re-evaluate key steps in alfalfa weevil IPM in the Western region: monitoring the pest populations, the economic threshold that requires action and early harvest to limit yield loss. But one critical emerging issue remains: insecticide resistance.

After many years of exposure, insect populations can develop resistance to the insecticide toxin, making it ineffective – an alarming development. Synthetic pyrethroids are a large class of insecticide with active ingredient names like cyfluthrin, cyhalothrin and cypermethrin and trade names such as Baythroid, Mustang Maxx and Warrior, among many others.

Pyrethroid insecticides are commonly used in forage crops because of their effectiveness and favorable cost. Failure of insecticide applications, and suspicion of resistance, has now been reported by growers and agriculturalists in at least four Western states. Documenting the degree of weevil resistance to insecticide and developing resistance management plans is an immediate priority.

Take-home message

Producers will need to stay tuned to local extension service offices for updates on alfalfa weevil research and management. ![]()

Kevin Wanner is the associate professor of entomology and cropland extension entomologist with the Department of Plant Sciences and Plant Pathology at Montana State University – Bozeman. Email Kevin Wanner.