Mixtures vary but can include a small grain (e.g., cereal rye, wheat, oat), annual ryegrass, a brassica (e.g., turnips, radish, kale) and an annual legume (e.g., crimson clover, arrowleaf clover and hairy vetch).

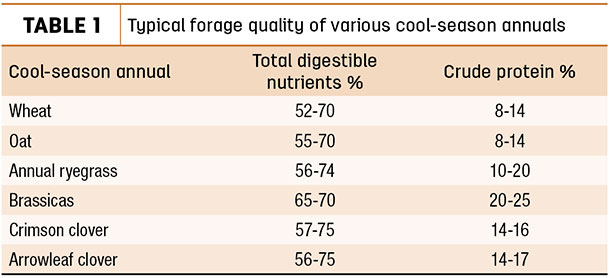

Alone, these forages are very nutritious (52 to 75 percent total digestible nutrients and 8 to 25 percent crude protein; Table 1), but when grazed in a mixture, they generally have a more uniform forage yield throughout the grazing season and have complementary forage quality profiles.

Research in Arkansas and Alabama has shown mixing small grains with annual ryegrass extends the grazing season by 20 to 30 days compared to a monoculture pasture. Typically, these systems are designed to maximum forage yield and quality to support an intensive stocker or replacement heifer program. However, many pasture-based beef cattle producers operate cow-calf operations.

The forage quality of cool-season annual mixtures exceeds the nutrient requirements of both pregnant mature cows and lactating mature cows. This is a result of the nutrient requirements of mature cows being at least 25 percent less than those of their growing counterparts.

Free access to cool-season annual mixtures can lead to mature cows gaining too much condition and being overweight. This leads to reduced conception rates and possible calving difficulty.

Limiting the animal’s access to these pastures on either a daily or a weekly basis will limit the amount of forage the animals can consume and prevent them from gaining too much condition during the winter months.

Limit grazing can take on a variety of different forms, but the premise stays the same: Limit the amount of grazing time animals have access to high-quality pasture and feed lower-quality feedstuffs during the other times.

The two main ways to do this are: Graze cool-season annual pasture for only four to five hours every two to three days, or allow animals access to cool-season annual pasture for 36 to 48 hours per week. In either scenario, animals should be put on stockpiled warm-season grasses or in a drylot with hay when they are not allowed into the cool-season annual pasture.

Regardless of the amount of time spent in the limit-grazed pasture, animals should always have free access to a fresh, clean water source. Research in Arkansas has shown cow-calf pairs grazing a wheat/rye/annual ryegrass pasture for two days per week produced the same cow, calf and rebreeding performance as cows fed unlimited hay plus a supplement, but limit grazing reduced hay consumption by 30 percent.

Limit grazing also increases forage utilization. Limiting the time spent in a pasture reduces the amount of time an animal has to create manure and lounging areas that limit forage availability and decreases forage loss to trampling.

Research in Oklahoma has shown limiting stocker cattle access to wheat pasture increased the carrying capacity of the pasture which, in turn, increased animal production per acre compared to a wheat pasture not limit-grazed.

Limit grazing allows cattle to get the nutrients they need without gorging themselves and gaining excessive condition. This method of grazing can also be used to adapt animals to new forages or to limit animal access to bloat-inducing forages like legumes.

To manage animals in a limit-grazing system adequately, it is important to know the average bodyweight and physiological condition of the cattle, the forage quality of hay or stockpiled forage and the forage quality of the cool-season pasture you will limit graze.

Nutrition specialists can determine animal requirements, but forage quality can only be determined by adequately sampling the pasture and the hay or stockpiled forage. For the most accurate results, pastures should be sampled two weeks before cattle are to start grazing and periodically throughout the grazing season. ![]()

PHOTO: These cow-calf pairs are limit grazing a wheat, crimson clover and T-raptor brassica mixture in Headland, Alabama, on Nov. 28, 2017. Photo by Leanne Dillard.

Kim Mullenix is an assistant professor and extension specialist, beef systems, with Auburn University’s Department of Animal Sciences.

-

Leanne Dillard

- Assistant Professor and Extension Specialist – Forage Systems

- Auburn University

- Email Leanne Dillard