Some producers may be trying to decide whether they should apply agri-chemicals themselves rather than hiring a local supplier. Will this save you money in the long run? There are a number of things to consider before jumping into the pesticide application business.

First, let’s discuss some basic considerations about applying pesticides. Here are 10 things we thought about.

1. How much land do you actively farm, and do you have the time to spray your own ground? The applicator will need a pesticide certification license and will need to regularly attend update training meetings in order to remain certified.

2. What crops do you grow that require pesticides (or herbicides, insecticides, fungicides, etc.) and liquid fertilizers?

3. When will the application timings occur during the growing season?

4. Do you have someone that can be dedicated when necessary to this task? Consider any potential conflicts with other farming operations during busy times of the season.

Some farmers who are involved with planting will use a custom applicator for burndown/residual herbicides and then apply their own post-emergence herbicides when things slow down after planting.

5. The applicator will need to understand what pesticides to apply based on the target pests, how to maintain, calibrate and operate the sprayer, how to mix in the correct order, and apply at the correct volume and speed.

There may be a small window of a few days when the chosen products perform best, so timing can be critical.

6. The applicator will need to know how application time of day, temperature, humidity and rainfall could affect the efficacy of the material, and you will need to assess how well the product worked on the target pest and if additional control measures are needed. If the application doesn’t do the intended job for whatever reason, who is accountable and what recourse do you have?

7. Will technologies such as GPS and variable rate controls be needed? These require another level of sophistication and understanding.

8. The farm will likely need applicator insurance in case anything happens or, in particular, if the applicator does any custom work for others.

9. Late-season applications such as fungicides in corn will require specialized equipment, so a custom applicator may be necessary.

10. Nozzles typically used for applying herbicides generally are not the best choice when applying fungicides, insecticides or liquid fertilizers.

So the addition of specialized multiple-nozzle body assemblies (turrets) that allow for a quick change to other nozzle types may be important if you are applying different types of pesticides.

Second, the farm will need to own a reliable sprayer. Sprayers come in many different sizes ranging from three-point hitch models that might have a 200-gallon tank up to self-propelled machines with high clearance that come with much higher price tags.

For this article, we will use an “example” farm operation. In our example, the farm has 200 acres of corn and soybeans sprayed twice each season (pre-emergence and post-emergence).

That means a custom applicator is treating about 400 acres each season for you. Custom-application rates vary based on geography and also on how many acres are being treated. Custom fees don’t directly include any of the pesticides that may be needed, so that’s in addition to the application cost.

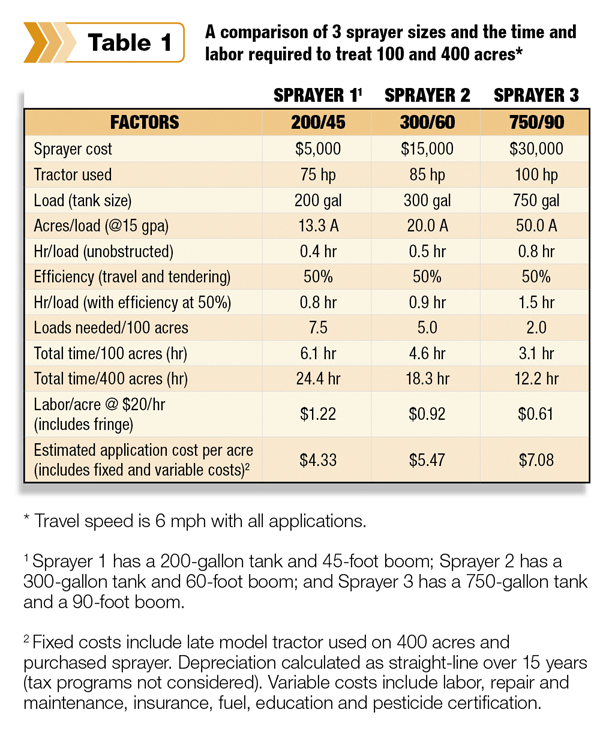

How much time does it take to spray 100 acres in a single application and then the entire 400 acres during the season? We will compare three examples provided in Table 1.

How much time does it take to spray 100 acres in a single application and then the entire 400 acres during the season? We will compare three examples provided in Table 1.

First, the farm is starting small and has a less expensive three-point hitch 200-gallon tank sprayer mounted on a 75-horsepower (hp) tractor (Sprayer 1).

The tractor is primarily dedicated to spraying at certain times of the year but is obviously used for many other tasks as well. In our example, 200 acres total being sprayed twice each season uses less than 5 percent of the tractor’s time based on 500 hours per year. Sprayer 1 has a 45-foot boom.

Some of the farm fields are smaller and have hills or miscellaneous obstructions like trees, fencerows, waterways or sinkholes, so the applicator may not be able to travel as fast and it will take more time to navigate.

In our example, the applicator is applying herbicide in 15 gallons of water per acre (15 GPA) and can treat about 13.3 acres with each tank load (Table 1).

The applicator sprays the corn ground first and averages 6 miles per hour. If the farm had a perfectly straight field that continued on for miles and the sprayer had a bottomless spray tank, you could treat almost 33 acres per hour. But the applicator has to turn frequently and head back to the barn to mix and refill the tank (tendering).

We will use a 50 percent application efficiency rate to account for turning, travel and tendering time. We already said that the applicator can spray 13.3 acres per tank, so it will require 7.5 loads with this 200-gallon sprayer to cover 100 acres.

Based on our approximate 33 acres per hour, without any problems and including our 50 percent application efficiency rate, it would take about 50 minutes to fill and apply a tankload. With 7.5 loads needed per 100 acres, that’s about a 6-hour job to spray the corn a single time.

On a nice day in May or June, this is certainly doable, although it could take two or three days depending on the weather. If we consider both our corn and soybeans and spray both twice, our total time to spray 400 acres per season with Sprayer 1 is 24.4 hours (Table 1).

Let’s compare this first option to a pull-type 300-gallon tank, 60-foot boom, with an 85-hp tractor (Sprayer 2). The applicator can spray 20 acres per load (at 15 GPA) with this sprayer and reach almost 44 acres per hour (Table 1).

With the bigger sprayer, the applicator would only need five loads to cover the 100 acres, and assuming the same speed and efficiencies, this would cut the time down to about 4.6 hours per 100 acres, or 18.3 hours for 400 acres, and reduce labor costs by about six hours (Table 1).

Finally, if the farm has an even bigger sprayer (Sprayer 3) with a 750-gallon tank, 90-foot boom and 100-hp tractor, the applicator could treat almost 50 acres per load, which would cover 100 acres in two loads.

This is assuming the same speed and efficiencies. This would cut the application time down to about 3.1 hours per 100 acres, or 12.2 hours for 400 acres, and reduce the labor needs by another six hours (Table 1).

If the tractor speed could be increased with any of these operations, this would improve efficiency and reduce costs.

Time increases the need for labor, but the bigger the sprayer and tractor, the higher the equipment costs. In this example, Sprayer 1 is relatively inexpensive, while pull-type Sprayer 2 with some level of sophistication would be intermediate in cost, and pull-type Sprayer 3 with a 90-foot boom would be an even higher cost (Table 1).

Of course, these costs will vary greatly depending on how the sprayer is set up and whether it is purchased new or used. Increased tractor size also increases cost of operation, and with these examples we went from a 75- to 100-hp tractor and we increased sprayer size. (For those considering a self-propelled sprayer, according to Kansas State University, one typically needs to spray 10,000 to 12,000 acres per year to justify this piece of machinery.)

We did calculate a crude cost per acre for each tractor and sprayer combination based on 400 acres total use. We considered the tractor and sprayer as fixed costs and labor, insurance, repairs and maintenance, education and fuel as variable in this comparison. The cost per acre ranged from $4.33 for Sprayer 1 up to $7.08 for Sprayer 3.

Keep in mind: A number of variables should be considered in these calculations and our analysis was not complete and should only be considered as a starting place.

For a more detailed economic analysis on buying versus custom-spraying, we suggest reviewing the following source (Kansas State University publication: Farm Management: Machinery). FG

Dwight Lingenfelter is also with Penn State University.

- William Curran

- Penn State University