While sunny, dry weather is needed to make high-quality field-dried hay, extended periods of dry weather can severely reduce yields if the crop is not irrigated, which very little is in the East.

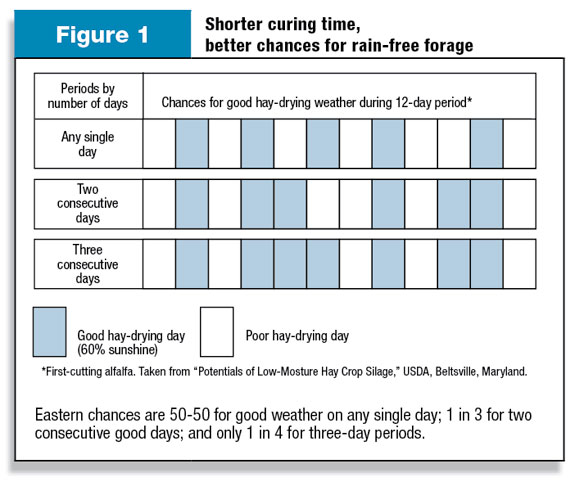

Abundant and frequent rainfall produces a bounteous crop but getting it cut and dried in a timely manner can be very challenging, as we have experienced in parts of the eastern U.S. and Canada the last two years (see Figure 1).

Much of the Mid-Atlantic region experienced unusually dry weather conditions during the 2005, 2006 and 2007 growing seasons.

Hay supplies were limited to the extent that even low-quality hay could be sold for a good price. By the end of this period, barns and hay sheds had been completely cleaned out.

Hay growers became somewhat spoiled because anything and everything could be readily sold. Costs of transportation worked against bringing in large quantities of hay from outside of the region, so there was a ready market for local hay.

Then weather conditions went to the opposite extreme in 2008 and 2009. We had abundant and frequent rainfall, especially during May and June.

The three- and four-day windows of favorable haymaking weather were few and far between, especially for first cutting.

Some first-cutting hay was not harvested until July, so even if it wasn’t rained on it was low quality because it was so overmature. A lot of hay was both overmature and rained-on.

So while there was/is an abundant supply of hay in 2008 and 2009, much of it was/is low quality with limited market demand.

Hay growers in some parts of the region went into the 2009 season carrying over half or more of their 2008 crop. Thus there is currently a glut of low-to-mediocre quality hay in our barns and hay sheds.

Also, demand for hay this fall has been lighter than normal. The abundant rainfall in late summer and fall along with moderate fall temperatures produced unusual amounts of pasture growth. This has greatly reduced the need to feed hay.

In addition, our primary hay market in the Mid-Atlantic region is the horse industry. Due to current economic conditions, horse numbers appear to be declining, further reducing demand for hay. Unless we have an unusually cold, snowy winter, it appears that overall demand for hay will be down this winter, at least in the Mid-Atlantic part of the region.

Even under the best of weather conditions, haymaking in the East is more challenging than in most of the West and Midwest, especially compared with irrigated hay production. It usually takes four to five days to get hay dry in May.

We are often laying the crop down on wet ground, especially in May, so not only are we dealing with the moisture within the plant but moisture being evaporated from the ground also comes up through the hay.

We cannot shut off rainfall, as can be done with irrigation, to allow the ground to dry before mowing. We also deal with higher air humidity levels, which impact drying rates.

Tedding at least once or twice is common to spread and lift the hay to allow greater radiation exposure and wind/air penetration through the hay.

Due to the frequency of showers and oftentimes damp ground, bales cannot be left in the field to air-out or cure before stacking into storage.

Most hay in the East is put into storage immediately after baling. Once stacked into storage, air flow around the bales is restricted, and if not sufficiently dry going into storage, some amount of heating in storage is likely.

Hay growers frequently face the dilemma of baling before the hay is sufficiently dry to avoid the coming rain showers and having the likelihood of some amount of mustiness developing, or delaying baling until the next day and having the hay rained on.

Given our humid climate and primary hay market being the horse industry, particularly the Mid-Atlantic region is better suited to grass hay production than alfalfa. Alfalfa is the major “hay crop” on dairy farms but most of it is harvested as silage, especially the spring and fall cuttings.

Timothy is generally the preferred hay within the horse industry in the East. Timothy being the latest of the grasses to reach maturity and the horse industry generally preferring fully headed-out timothy hay, grasses are a better fit for hay production in the Northeast and Mid-Atlantic regions than is alfalfa.

Because of the difficulty of putting up high-quality alfalfa hay, some of the top-producing dairy operations in the region are moving more and more to purchasing “western” alfalfa hay to complement their alfalfa haylage.

By purchasing western alfalfa they can provide a more consistent high-quality alfalfa hay to meet nutritional requirements than they can by producing hay on the farm under our weather conditions.

Another factor that affects hay quality in the East is that we have very few farmers whose primary enterprise is hay production.

Most farmers grow grain crops as well as hay, either for on-farm feed or as cash crops. Grain crops tend to have priority over hay – corn planting comes before hay harvest, so cutting is delayed and quality lost.

Along with this, most hay producers in the East are not adequately equipped to harvest and store large quantities of hay on a daily basis.

Most of the horse industry in the East prefers the small square, 40-pound bales and most Eastern hay growers do not have automated bale-handling systems that would enable them to handle large quantities of hay on a daily basis when weather conditions are favorable.

So between weather conditions and limited bale-handling capacity, each cutting can get strung out over a month or six weeks, especially for first cutting.

In spite of the challenges in making high-quality hay in this part of the country, we have seen increasing interest in hay as a cash crop in recent years.

Some of this increased interest is undoubtedly related to the decline in the number of dairy farms. Most of these farmers have haymaking equipment and unless the farm is being sold for development, cash crop hay is usually a logical alternative enterprise to keep the land in agricultural production.

And depressed grain prices four to five years ago, along with high hay prices and short supply markets, encouraged some grain producers to get into hay production.

I’m seeing more interest in hay and pasture educational programs in the Mid-Atlantic region now than anytime in my 30-plus years in Maryland and from what I’m told, for probably the last 50 to 75 years (I haven’t been around quite that long to know firsthand). FG

Les Vough

Forage Crops

Extension Specialist

University of Maryland