Manure storage and hauling is a significant expense on many farms. Rather than thinking of it as an expense to be minimized, let us think of it as an investment opportunity to be maximized. A large portion of your cash expenses go toward growing or purchasing feed for your livestock. Manure is the opportunity that comes out the other end of this process. Since you already paid for the manure, it makes sense to maximize the return on that investment.

Managed properly, manure can be an excellent source of valuable nutrients. Managed poorly, it can lead to substantial nutrient loss and risks to water quality, especially when applied long before a crop is present to take up the nitrogen provided by manure.

Bacteria in the soil convert ammonium-nitrogen from manure or fertilizer to nitrate-nitrogen in a process called nitrification. The nitrate molecule carries a negative charge and does not adhere to negatively charged clay particles in the soil. It is also very soluble in water and, consequently, can readily leach from the soil. Ammonium, however, tends to stick to soil, so the leaching risk is lower. Research has found that nitrification slows considerably when soils at the 4-inch depth are at 50ºF or cooler. When manure or other sources of nitrogen are applied to warmer soils, the more rapidly ammonium will convert to nitrate, and the greater the risk of losing the nitrogen prior to when the crop can take it up.

Research from Iowa and Minnesota suggests that applying liquid swine manure in the fall before soils have cooled to below 50ºF can be a costly decision. Pushing manure application to later in the fall or waiting until spring can help to prevent nitrogen loss and better match nutrient availability with nutrient demand by crops. Swine manure has a greater proportion of nitrogen in the ammonium form (approximately 70% to 80%) compared to dairy slurry (approximately 50% of the nitrogen is in the ammonium form), but the same nitrification process will occur with dairy manure, and significant nitrogen loss can still occur.

At the Northeast Research and Demonstration Farm near Nashua, Iowa, a five-year study from 2016 to 2020 in a corn-soybean rotation with liquid swine manure injected at 150 pounds of nitrogen per acre showed an average corn yield loss of 38 bushels per acre when manure was applied in early fall (soil temperatures greater than 50ºF) compared to late fall (soil temperatures less than 50ºF). On continuous corn plots receiving 200 pounds of nitrogen per acre from manure, spring application averaged 28 bushels per acre greater yield than late-fall-applied manure.

Similar fall swine manure timing studies in other locations in Iowa and Minnesota have shown corn yield losses in the 10-to-15-bushels-per-acre range. Averaging the data from these studies along with the Nashua data, the corn yield difference over 18 site-years of data was 21 bushels per acre. Using an average corn price of $4 per bushel, this results in an $84-per-acre loss from applying manure too early. The manure still has value, but early application gives a much poorer return on investment.

On the other hand, yield was not as greatly impacted when dairy slurry manure was used in a two-year study from 2019 to 2021 in continuous silage corn in west-central Minnesota. The corn with early and late-fall-applied manure yielded similarly, likely due to the soil temperatures being cooler during that time of year compared to northern Iowa. Soil temperatures dropped to below 50ºF within one to three weeks in that study depending on the year, and conditions were generally dry. With every fall being different, it is still critical to limit your nutrient loss risk by applying manure once soil temperatures have cooled to below 50ºF.

Cover crops increase your return on manure investment

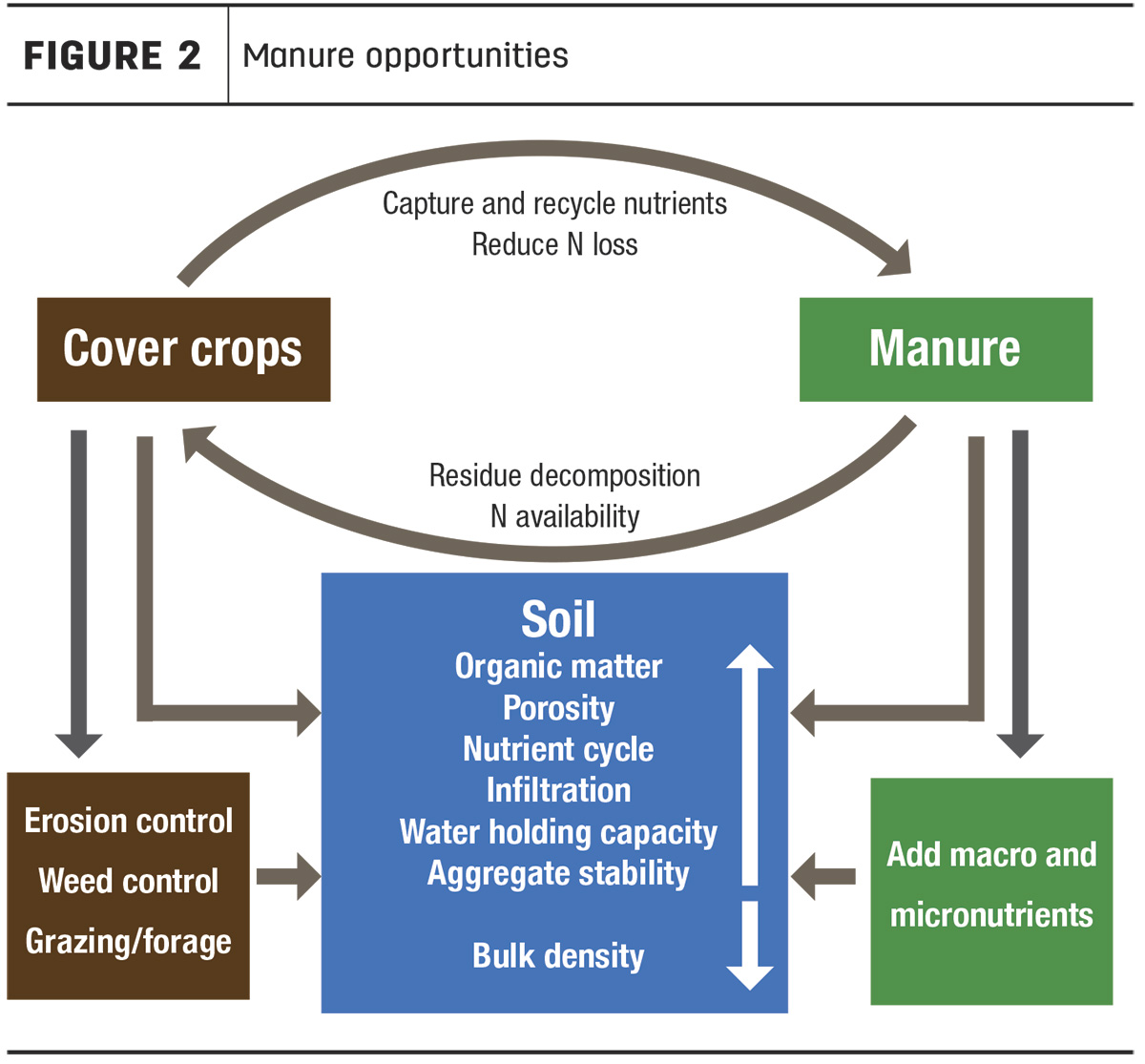

Data from the Nashua study showed that drilling a cereal rye cover crop after the early fall manure was applied reduced nitrogen loss from tile drainage by 35% in corn plots the following year. There was no yield difference when cereal rye was included in the rotation. The average nitrogen loss reduction with cereal rye was 14 pounds per acre per year over the five-year study. Factoring in the value of that lost nitrogen at today’s fertilizer prices makes the return on investment for early fall manure even poorer. Saving that nitrogen with the cover crop captures almost enough value to cover the cost of purchasing the seed.

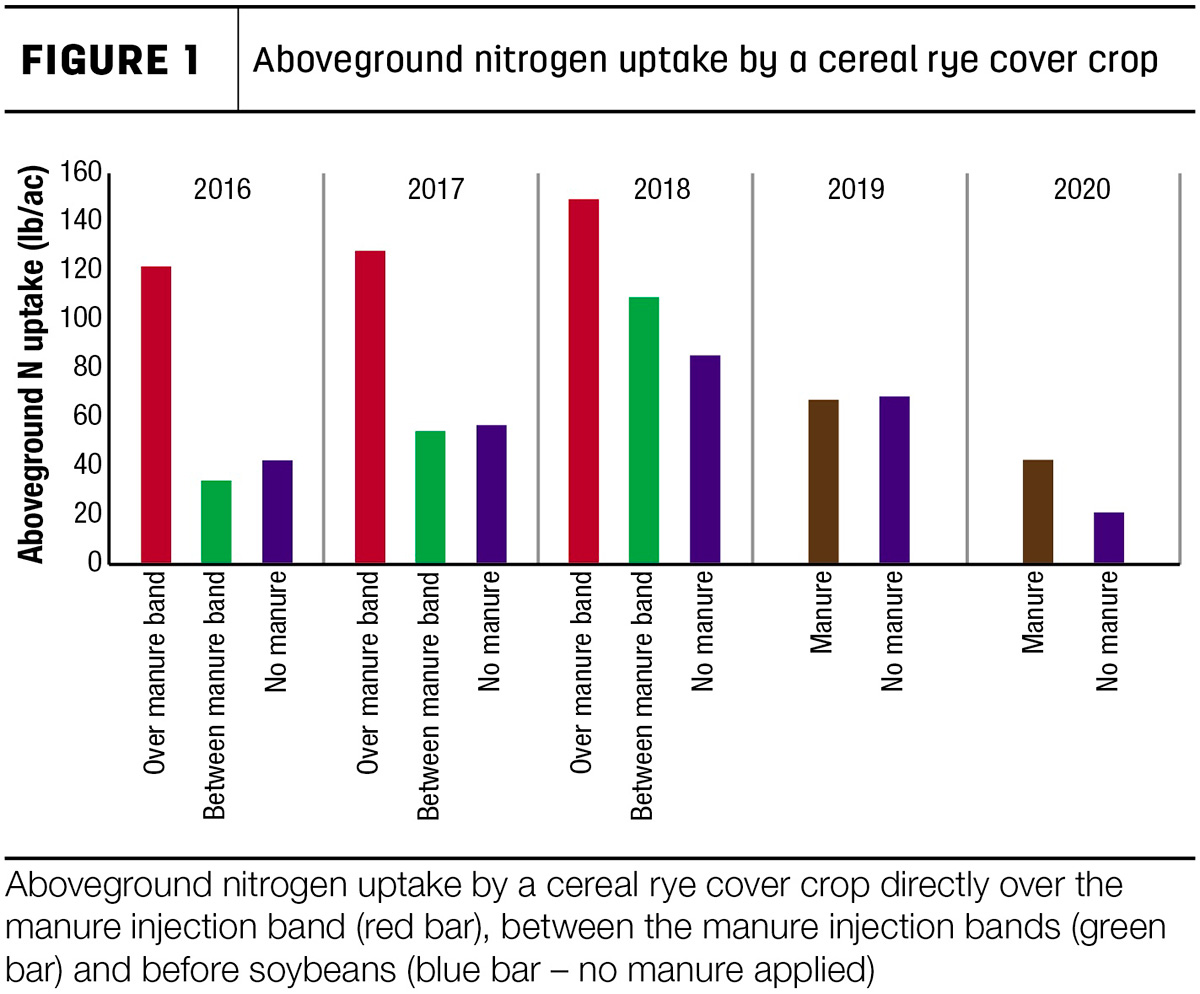

There were substantial differences in cover crop growth and nitrogen uptake in the aboveground biomass directly over where manure had been injected compared to between the injection bands in three of the five years (Figure 1).

On average, the cover crop took up about 79 pounds of nitrogen per acre on plots receiving 150 pounds of nitrogen per acre from manure. In plots going to soybeans where no manure was applied, the cover crop took up about 53 pounds of nitrogen per acre. These results suggest that the cereal rye took up significant residual soil nitrogen and likely took up nitrogen from the manure itself. It was not done in this study, but research in Minnesota showed that with low-disturbance manure injectors, it is possible to establish a cover crop earlier in the season and wait to inject manure into it until later in the fall or the following spring. This can help optimize application timing in a cover crop system.

Factoring in reduced soil erosion and the many other benefits of keeping the ground covered makes cover crops a great investment on any crop field, and especially on fields receiving fall manure. Research has shown that the average erosion reduction from cover crops on reduced-till fields is 6.5 tons per acre. Using a conservative number of $10 per ton of soil, the value of the cover crop for reducing erosion would be $65 per acre. This benefits the farmer directly by protecting future productivity and benefits society by keeping sediment out of the streams. The true value of topsoil is almost priceless because it is the foundation of life itself. The fully actualized cost of not protecting vulnerable fields with cover crops is too staggering to calculate.

Protect your bottom line by timing your manure applications closer to crop nutrient demand and keeping the ground covered with a living root year-round.