Costs of production are a common theme of farm profitability. However, it is also often confusing, elusive and changing.

Theory

When talking about profitability, the economist in me always starts with the profit equation. At its simplest, it is:

Profits = (price per cwt – costs of production per cwt) x hundredweight sold

With respect to price, the economics textbook tells us that commodity producers, such as those who produce milk, are price takers. While producers can and do affect the premiums they receive, the base/class price is set by macro market conditions outside the control of the individual producer.

However, being a price taker does not mean producers are cost takers. While some cost items are in that price-taking realm, such as commodity feeds, other costs are more in the control of the individual producer. That same economics textbook tells us that cost containment is and should be a major driver of profitability.

There are many metrics for costs, but the most important for the profit margin is costs of production per hundredweight. That metric has two parts – a numerator and a denominator.

The numerator is how much was paid for inputs and services while the denominator is how much was produced and sold. Costs of production per hundredweight can be reduced by decreasing costs per cow (numerator), increasing production per cow (denominator) or better yet – both.

Evidence

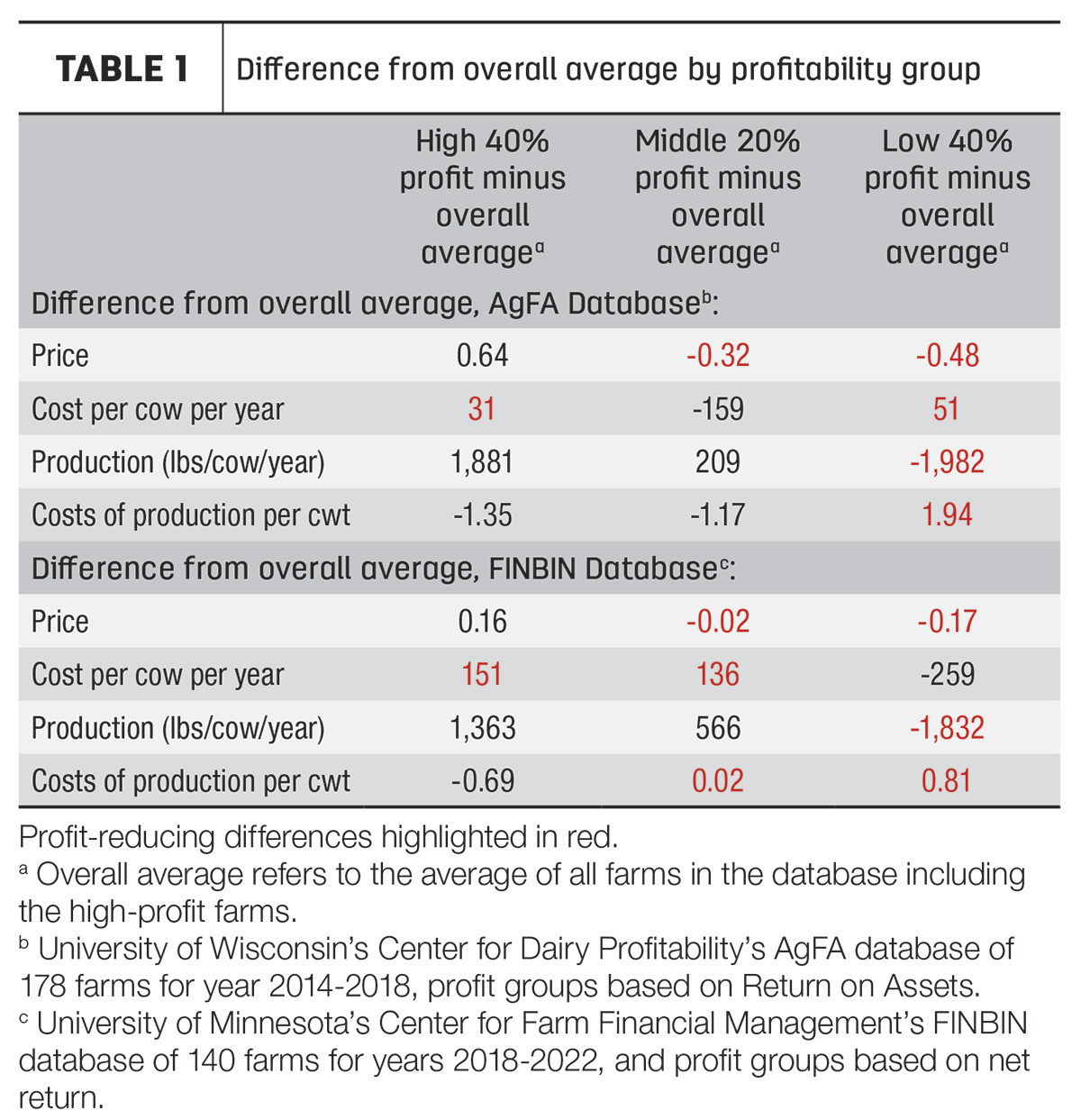

Does the textbook stand up to the scrutiny of real life? Table 1 shows results from two different databases of actual farms, two different five-year time periods and two different measures of profitability (return on assets and net returns).

Not surprisingly, regardless of the time period, database or measure of profitability, the high-profit farms had a higher average price, a lower cost of production per hundredweight and produced more milk per cow. This supports the point that there is no single silver bullet to profitability and that a little bit better in all areas of revenue, costs and production matters.

Another interesting result shown in Table 1 was the breakdown of costs of production per hundredweight into its numerator and denominator parts. In both databases, the numerator – cost per cow – was actually higher for the high-profit group; however, the denominator – hundredweights of milk produced per cow – was higher yet. Taken together, the ratio of costs of production per hundredweight was less for the high-profit groups due to relatively more production per cow. These results give some credence to the saying that one must spend money to make money. Of course, the extra spending must result in relatively more production.

Results are a little more mixed with the middle 20% profit group. In the Wisconsin database for the years 2014 to 2018, the middle group made a profit by ratcheting down costs per cow while maintaining production to make up for a lower price. The middle 20% of the Minnesota database for years 2018 to 2022 traded off slightly more costs per cow with slightly more production per cow, leaving them in the middle.

Contemplation

Having studied the evidence, my next question to my students would be, “What does this mean in terms of what the farm manager should do tomorrow after breakfast?” This question is often met with that deer-caught-in-the-headlights look. Let’s start with the current economic environment.

Prices appear to be in the lower part of the milk price cycle. While there is a wide range for the length of the cycle, the average from peak to low is around 13 months, and from peak to peak is about 36 months. The last peak in Class III prices was May 2022. Thus, on average the next low ought to be around mid-year 2023 and the next peak around the first half of 2025. However, the range is wide, so don’t set your clocks by these averages. What we can take away from this information is a higher probability of being at the lower part of the price cycle compared to 2022 for the months ahead.

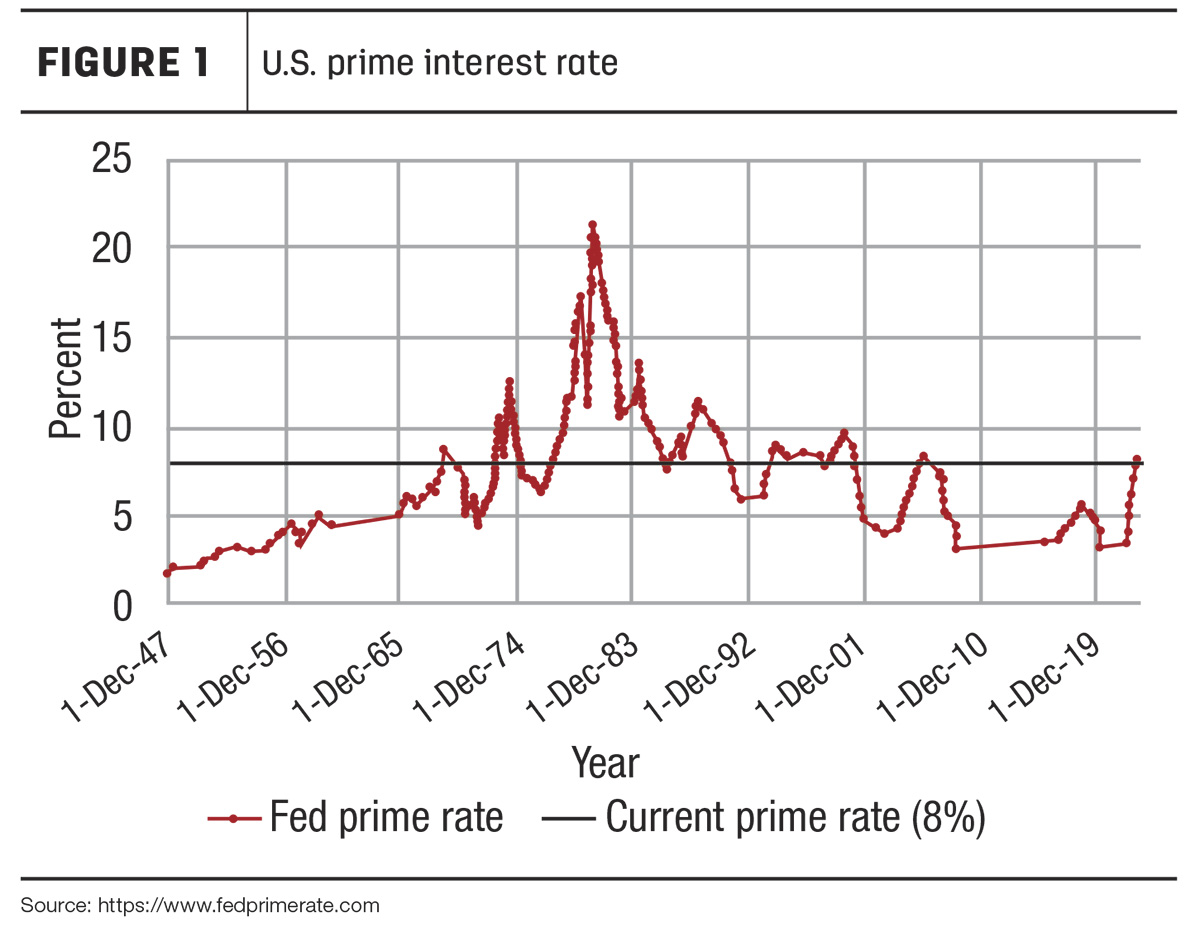

Interest rates are climbing (Figure 1) and have not been this high since the early 2000s. This adds to the cost of production depending on debt levels and makes investment in more efficient capital assets more expensive.

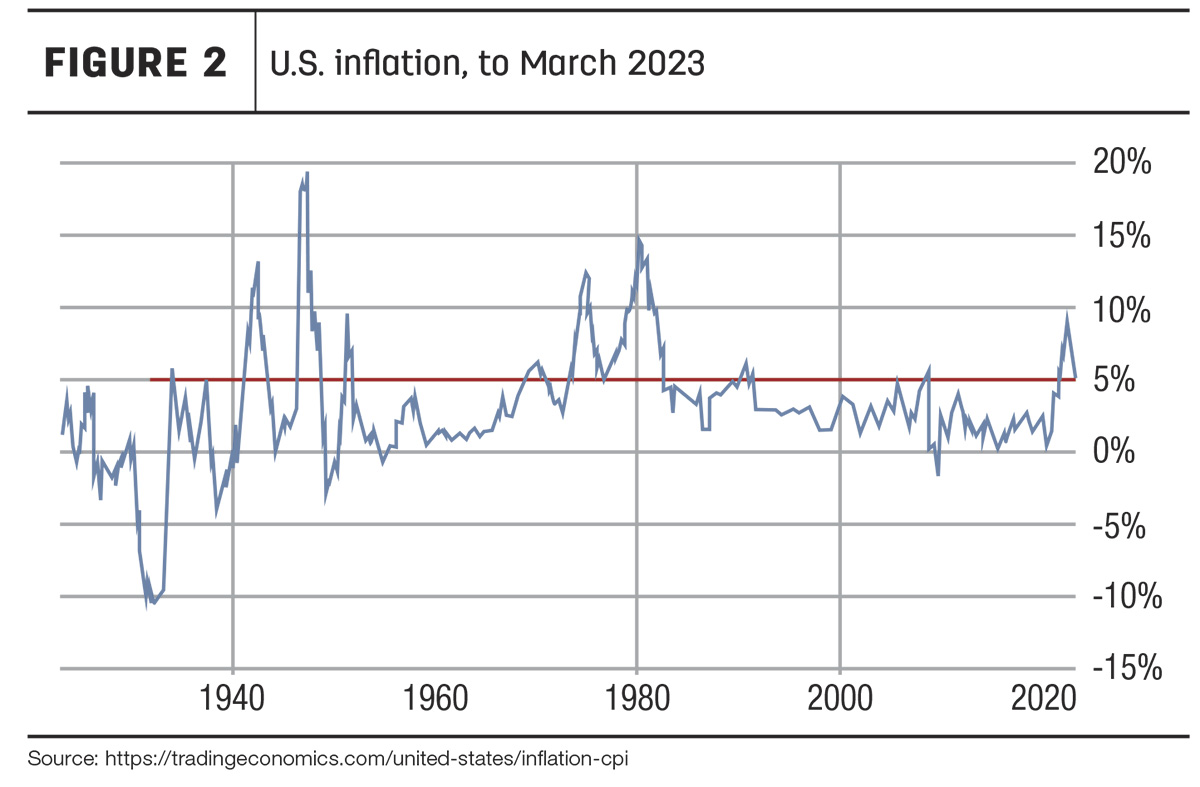

Inflation appears to be softening but is still high (Figure 2), and in fact, it is the highest it has been in 30 years. This impacts the costs of inputs and services. At first, inflation was thought to be transitory, a post-pandemic aftershock. Again, who knows, but transitory seems to be morphing into something more structural.

Finally, the industry continues to be challenged by labor issues (cost and availability), supply chain issues, oil prices and geopolitical uncertainties.

Taken together, it paints a picture of uncertainty in the least and a higher probability of softer prices. While the prospect of lower prices may add some urgency, managing for lower costs of production per hundredweight is always good business. Lower costs of production per hundredweight provides a cushion that will absorb price decreases during times of poor prices and enable greater debt repayment, building of working capital and investment when prices are higher.

Finally, let’s contemplate a little longer view. There appears to be a new and exciting frontier of technologies in robotics, remote sensing and data handling capabilities that if managed well may create a lower cost structure. However, it is not a one-size-fits-all adoption. Different technologies are appropriate for different situations based on scale, management capacity, business model and other factors.

For example, the early advantage touted for robotic milkers was labor savings. While certain kinds of labor savings may take place, other labor needs may increase or at least change. The question may not be whether a new technology will reduce labor costs but rather, what are the second-order effects of scale, scope or re-directing labor and management time to higher and more productive uses? How the whole system is managed to incorporate and take advantage of new technologies may be just as important as direct effects.

So, yes, costs of production are the focus of discussion yet again. The textbook and real-world evidence suggest we should expect this. New emerging technologies may offer new ways to change the cost structure. However, no matter how sophisticated the technology, the profit formula has not changed. The totality of management decisions must still be measured by the combined effects on the parts of the profit formula – price, lower costs per cow and/or higher production per cow.

References omitted but are available upon request by sending an email to the editor.