Heterosis is not exactly a new concept in the cattle world. For decades, commercial producers have known that breeding cows of one breed to bulls of another usually yields offspring that outperform the expected average between the two in many important traits. And while most understand and appreciate the fact that heterosis (also known as hybrid vigor) exists and can improve their operations’ bottom lines, the question remains in many minds: Where exactly does heterosis come from?

That was the question Raluca Mateescu, a professor of quantitative genetics and genomics with the University of Florida’s (UF) Department of Animal Sciences, sought to answer for producers in her presentation at Cattlemen’s College at the National Cattlemen's Beef Association (NCBA) convention in Orlando, Florida.

When it comes to chasing genetic improvement in a cow herd, producers have two primary tools available to them: selection and crossbreeding. The two primary benefits of crossbreeding are complementarity – which takes advantage of each parent breed’s strengths while minimizing the impact of its weaknesses – and heterosis – the bump in performance you get from the mating of genetically distant individuals.

Mateescu advised producers that genetic data such as dominance values and expected progeny differences (EPDs) can have too much value placed on them if not applied in the right context.

“Dominance value is important in determining how that individual will perform but not necessarily for its offspring,” she said. “Progeny will only inherit half of the genetic merit of an individual.”

Another important thing to consider is which traits are most ripe for improvement through heterosis. Generally, structure and carcass traits are the most heritable (likely to be passed on and able to be measured), growth traits are moderately heritable, and reproductive traits such as fertility and longevity are the least heritable. Those lowly heritable traits, Mateescu said, are the ones most likely to see improvement through crossbreeding.

“Traits that have low heritability have high heterosis,” she said. “Those traits I’m having a hard time selecting for, I get a bump in profitability with crossbreeding and heterosis.”

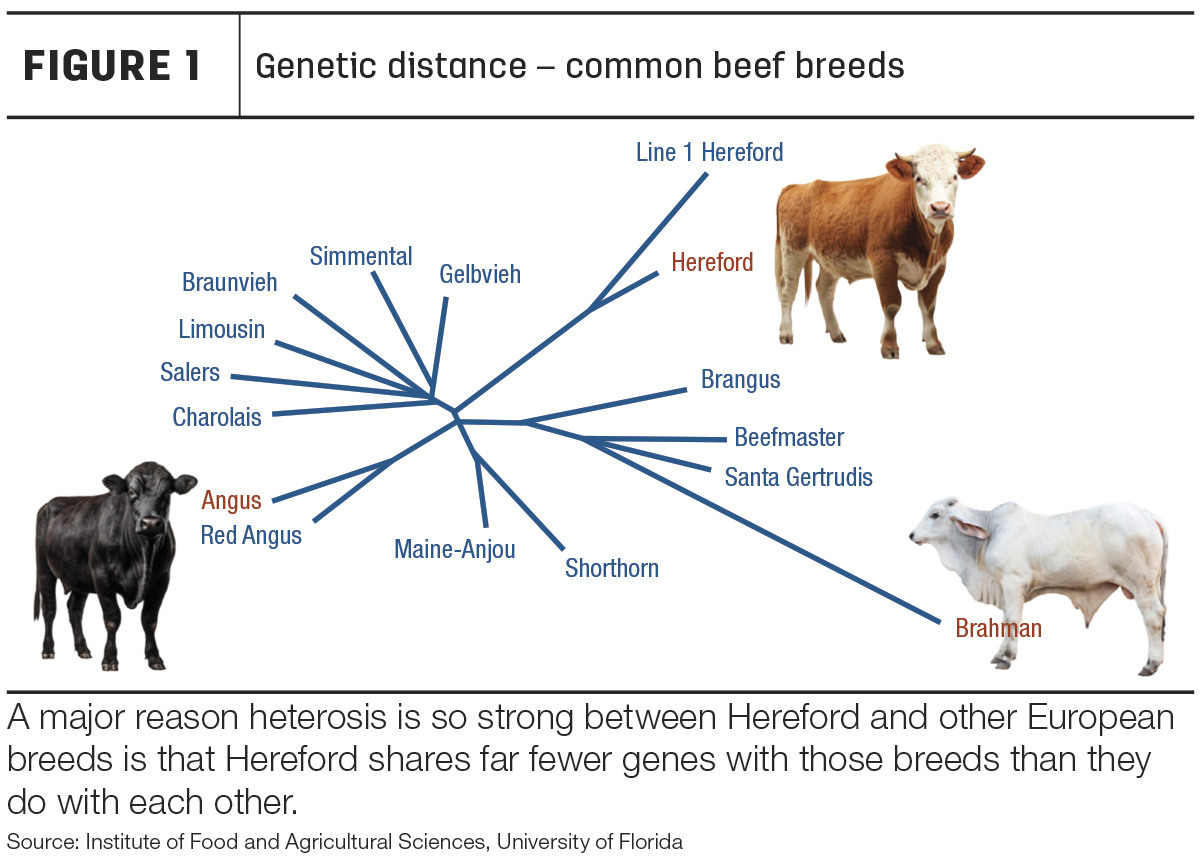

The Hereford breed has long been touted as the great purveyor of heterosis in U.S. beef herds. A closer look at its genome provides a clue as to why, Mateescu demonstrated (Figure 1).

Hereford is more genetically distant from other Bos taurus breeds than any other commonly used British or continental breed. Brahman and other Bos indicus-influenced breeds, of course, provide even more distance and therefore even higher levels of heterosis.

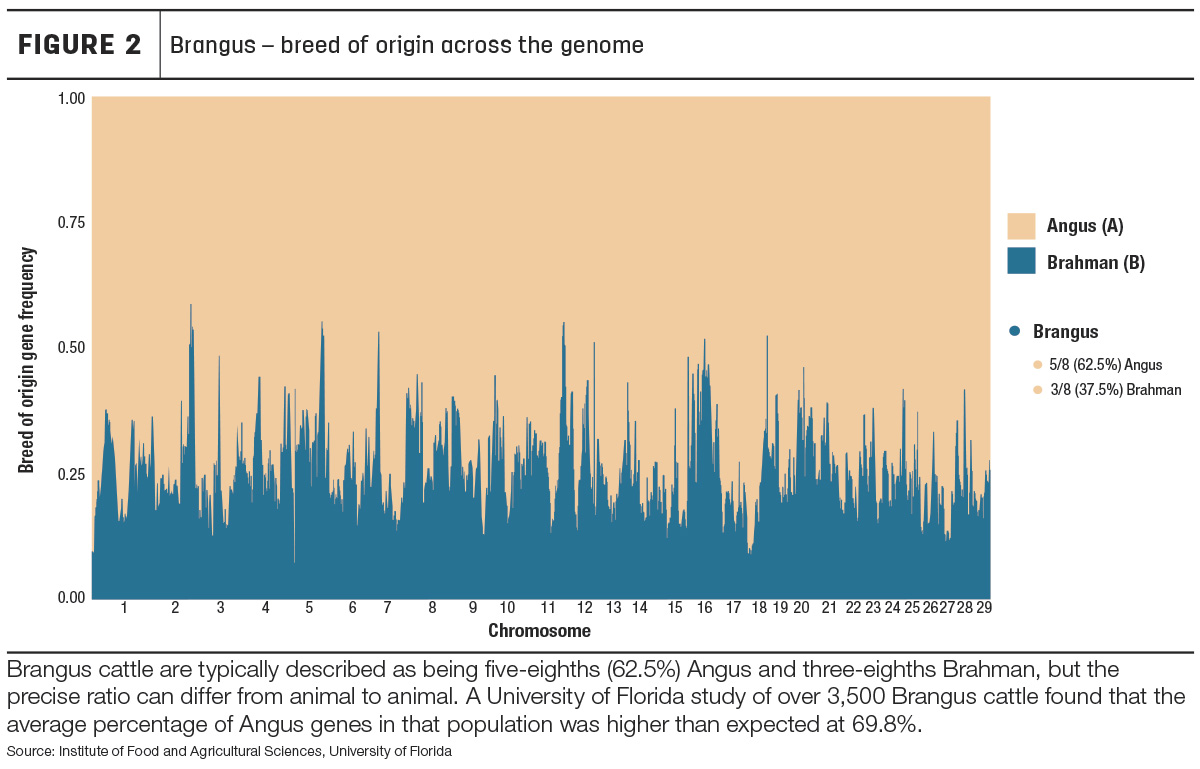

One issue Mateescu sees with producers is a failure to appreciate the genetic differences of individual animals within a specific breed. For example, Brangus is officially defined as being five-eighths Angus and three-eighths Brahman (Figure 2). However, that doesn’t mean every Brangus animal has inherited the same three-eighths of its genome from its Brahman ancestry.

“Animals can have the same percentage but be very different genetically. There is tremendous variation across the genome,” Mateescu said. “But estimating heterosis is actually fairly easy if you have the genetic markers [genome].”

Producers need to ask themselves which regions of the genome are important for different traits and which regions contribute the most to heterosis. With the genomic tools available today, those answers are more readily available and, perhaps most importantly, applicable than ever before.

Once an understanding is built of where heterosis comes from and how it can be implemented on an operation, the final question Mateescu said producers face is how to retain those benefits in a herd from one generation to the next. Heterosis is at its peak in the first generation (F1); if F1 crosses are crossed, half that heterosis is lost. The further away you get from that initial cross, the less heterosis those cattle have – unless, of course, a good plan is put in place. Mateescu said such a plan should include rotational breeding. The more breeds exist in a rotation, the more heterosis will exist in a herd. However, there is a management cost associated with each additional breed added to the rotation.

“Most producers,” she said, “probably don’t want to go higher than a three-breed rotation.”