Twenty years ago, achieving satisfactory reproductive results on a dairy was a key measure of viability. Today, our knowledge of, and ability to, achieve reproductive metrics has revolutionized how we think about reproduction. These changes have allowed us to decouple our thinking on reproduction.

Today, we no longer hope for enough heifer calves or need to push to create enough replacements in our herds. We can now decide on an economically justifiable conception rate and what animals we want to get heifers from. With our additional capacity, we can produce high-quality beef calves that are recently selling for over $600 at birth. Cull cow prices can also be great for quality animals. We now think about heifer calves in terms of specific numbers per week or month. Our excess capacity to produce beef calves is a huge opportunity for dairy.

Over time, bringing in a replacement heifer must result in one dairy animal leaving the farm. If a cow does not leave the farm, then the farm’s herd numbers are growing. Depending on the size of the farm, the timeline can be days to months before another cow must leave.

We must also change our thinking about raising replacements and selling cull cows. In a dairy animal’s lifetime, she can yield both milk and beef (if she does not die and is fit for slaughter). The cost of replacement is not the cost of raising that animal, but it is the difference between its raising cost and the cull cow price multiplied by the probability of it being sold for beef.

Intentionally managing terminal lactation cows (a cow that has been reproductively culled at least 60 days prior to sale) can yield better cull cow prices and a higher probability of being sold for beef. By definition, increasing the intrinsic beef value of cows reduces the cost of dairy replacements (raising cost minus beef value). Dairies need to set goals for percent of farm revenue from milking animals sold for beef (cows in their terminal lactation) and for a maximum level of death loss. I like to call these animals “milking beef” because it is a constant reminder that our primary value from these animals is beef. To achieve goals for terminal lactation, a dairy must maintain good management of the heifer replacement pipeline, and these need to be decisions that occur years in advance.

By managing for terminal lactations, the dairy is intentionally identifying cows unlikely to complete a lactation or have a profitable future. The worst thing that could happen to one of these cows is to get pregnant, thereby prolonging unproductive life (a dry period) and increasing the likelihood of disease and possible on-farm death (during parturition). When we manage these animals for the goal of selling as beef, we are also able to generate revenue from these animals via milk production. This type of management waits only for a need to reduce stocking density or her more healthy, more promising replacement to show up at the farm gate.

A few good ways to make early do not breed (DNB) decisions on your milking beef is to look for the following animals in their first week of lactation:

- Animals whose prior lactation output puts them in the bottom 2% to 3% percentile

- Animals who have more mastitis cases than they do lactations

- Animals who have more lame events than they do lactations

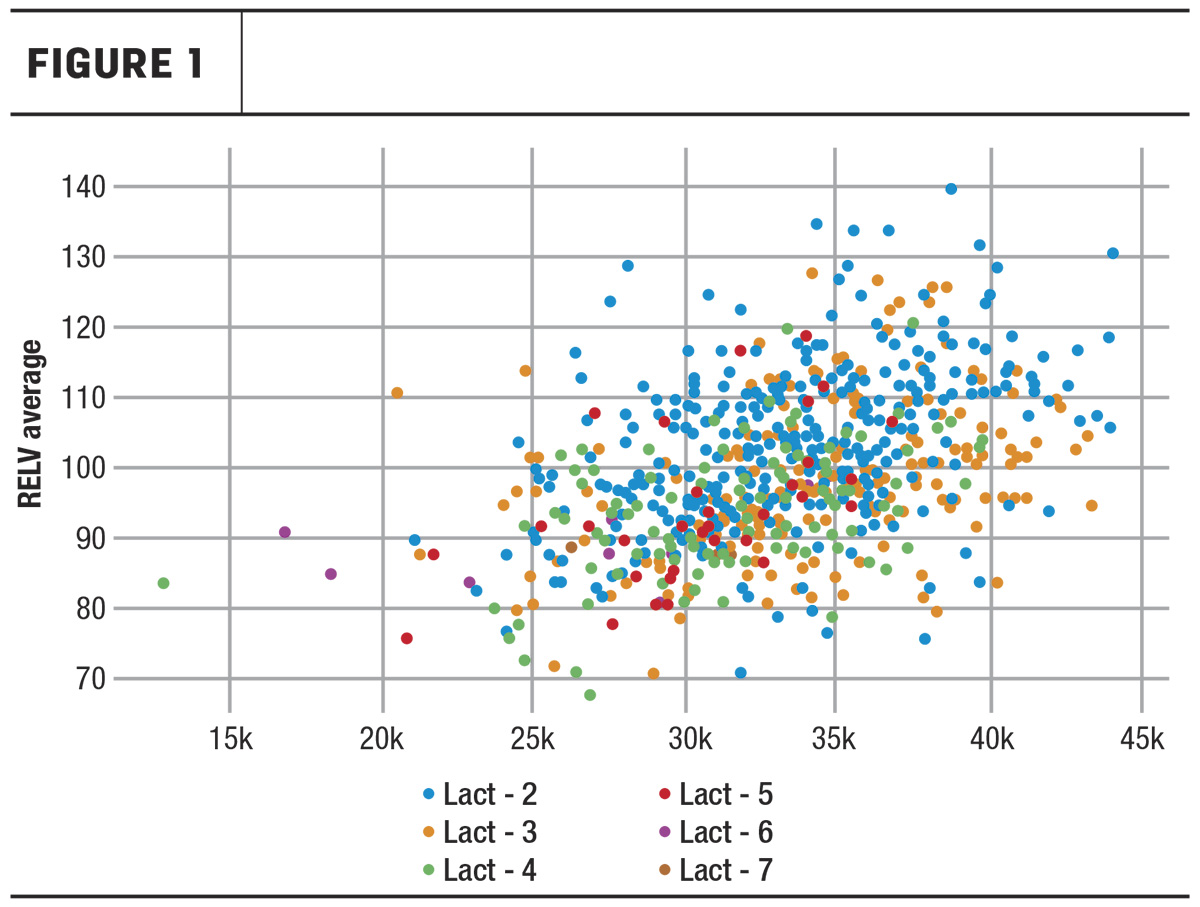

Figure 1 is a scatterplot of previous lactation 305-day milk compared with current lactational performance. There is a clear linear trend here: Cows that did well in the previous lactation do well in thie lactation. By creating a cut-off (red line) at freshening to identify the lowest-production animals as milking beef, we can improve herd-level milk production by removing these animals from the herd. This allows older, more productive and healthier animals to stay longer due to reduced culling pressure as new replacements arrive.

Causes for leaving a dairy are primarily related to low production, mastitis and lameness. Animals known to be predisposed to those conditions should be managed for their beef yield and value. Reducing the population of these animals in your herd also has marked improvements in the dairy value of the herd. These herds tend to have more older cows that produce milk effectively and don’t have health issues, which become easier and more profitable to manage.

Before you begin, you must also consider the impact on beef-on-dairy calf sales. This approach of keeping higher percentage of herd open and DNB could produce a lower calf crop. Terminal lactations are likely animals that would have attempted to produce a beef-on-dairy calf, and in some markets that calf has high value. To help understand, look at your farm’s history of the animals that were terminal in the past three years. Look at the data and answer two questions: What is the probability the terminal animal would have actually made it to the next lactation, and what is the probability they die or are condemned before slaughter? You can use your historical data to understand the potential profitability of your milking beef by post-hoc analysis of those same animals.

The success of a milking beef program requires both a high degree of success in reproductive management and transition health management. Have both? You’re on the right track to success.

If you are not managing in this way already, talk with your beef buyer, your herdsman, nutritionist and other consulting teams. What would dedicated effort for beef yield do for your revenue? What does that management look like? To implement this strategy on your dairy, start planning today so you can ensure your heifer replacement pipeline can supply the replacement of milking beef.