The ingenuity of farmers should never come into question. They’ve come up with hundreds of ways to utilize twine and duct tape. When times are tough, farmers find solutions. That’s why its no surprise that in times of drought farmers rekindled an old idea of stretching their feed supplies further.

The alkali treatment of crop residue is a practice that could transcend drought management, said Dave Combs, nutrition professor at the University of Wisconsin – Madison.

In his presentation at the Midwest Forage Symposium earlier this year, he stated that as corn yields increase, the biomass per acre also increases. With more corn grown for ethanol, Combs indicated the premise of using both the remaining distillers grains and fiber has its merits.

Citing the USDA, he said the six states in the Corn Belt produce 132 million metric tons or nearly 68 percent of the nation’s corn stover.

As mentioned, this is not a new concept. The alkali treatment of crop residues has been tried with calcium, sodium hydroxide and ammonia. According to Combs, calcium or lime wins out because it is not as caustic as ammonia and more environmentally compatible than sodium hydroxide. It is also relatively economical at $20 to $30 per ton.

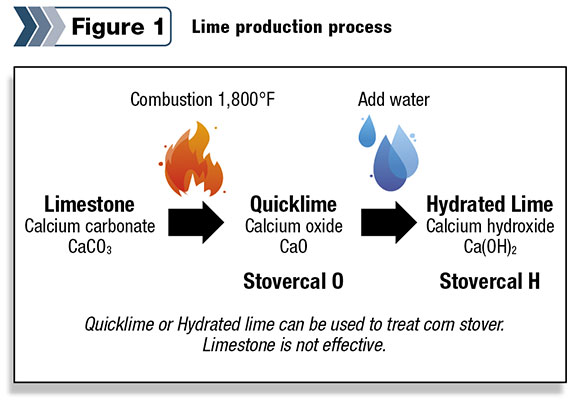

It is important to distinguish the different forms of lime, as shown in Figure 1 .

First, there is limestone, or calcium carbonate. Using combustion at 1,800°F, limestone is converted to quicklime or calcium oxide.

Adding water to quicklime converts it to hydrated lime or calcium hydroxide.

Limestone cannot be used to treat corn stover as it has no effect on fiber digestibility, Combs said.

However, quicklime and hydrated lime are both sold for this purpose as Stovercal O and Stovercal H, respectively.

Since quicklime reacts with water to form hydrated lime, Combs warned that many safety issues arise with its use. “You need to be careful in how you handle it,” he said, noting it should be stored in a dry location.

When making a slurry, the quicklime should slowly be added to a large volume of water to avoid boiling or the rupture of containers.

Workers should take plenty of precaution, as quicklime dust will cause severe irritation or burning of the eyes, skin, respiratory and GI tract.

It is very reactive with water, including perspiration on the skin and moisture in tissues in the lungs and esophagus. Eye protection is needed, and contact lenses should not be worn. If contact is made, use soap and water to remove the dust.

“Calcium hydroxide is much safer and easier to work with,” Combs said.

The process

“There is no exact formula in terms of processes,” Combs said.

When treating the stover on the farm, the stover should be chopped at 3 to 6 inches to reduce the particle size and increase surface area. A tub grinder could also be used to shorten the particle length.

Either quicklime and water or hydrated lime should be added, along with enough water to make a 50 percent dry matter feedstock. It should be stored in a silage bag or bunker for at least seven days prior to feeding to allow the full reaction to take place.

To apply treatment in the field, begin by windrowing the stover. Apply the lime to the windrow and follow behind with water.

Then use a field chopper to pick it up off the field with a field chopper. Combs warned the dust during chopping could be dangerous, and safety precautions should be taken.

For 1,000 pounds, the recipe would be 950 pounds dry matter corn stover, 50 pounds lime and 1,000 pounds water.

“To treat 50 tons of 90 percent dry matter stover, you need 10,600 gallons of water,” Combs said. “You’re not going to do that with a garden hose.”

Considerations for the process should include how to grind the stover, if quicklime or hydrated lime will be used, how much lime is needed to achieve 5 percent calcium application and how much water is needed to achieve a 50 percent dry matter.

Feed applications

Lime-treated corn stover can be used in cattle feed as a replacement for corn grain or forage.

Studies at Iowa State University and the University of Nebraska show lime treatment significantly improves the digestibility of corn stover and cobs in beef cattle diets.

For growing cattle, lime-treated stover can replace a significant amount of corn grain, especially if fed with distillers grains. It can be fed to yearlings through finishing. A two-to-one ratio of distillers grains and treated stover can replace up to half of the ground corn in feedlot diets.

About 10 to 15 percent units of corn grain can be replaced with lime-treated stover without affecting dry matter intake, average daily gain or feed efficiency in background and finishing diets.

“In terms of beef cattle performance, this seems to be working very, very well,” Combs said.

Research at Purdue University looked at whether or not lime-treated corn stover could serve as a replacement feed for corn silage in lactating dairy cattle.

Over the course of 21 days, 56 mid-lactation dairy cows were fed one of three diets: a control diet containing 37.5 percent of the diet’s dry matter as corn silage, a diet with one-third of the corn silage replaced with treated stover or a diet with two-thirds of the corn silage replaced with treated stover.

Milk production per cow held at 65 pounds across all three groups. Dry matter intake also remained the same at 49 pounds per cow per day.

In a study by USDA-ARS and the University of Wisconsin – Madison, researchers looked at the production and digestion responses of lactating dairy cows to substituting corn grain for lime-treated corn stover.

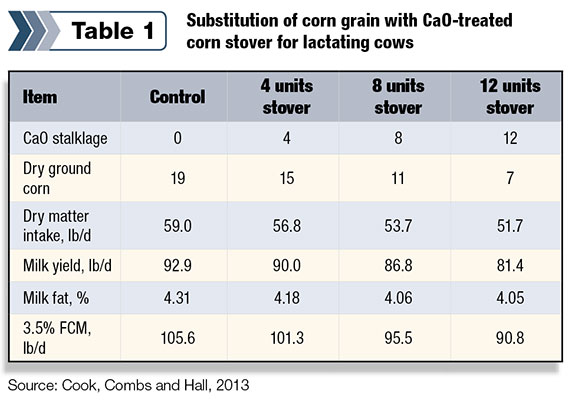

Four treatment diets were fed to 64 cows. The control diet had corn grain at 19 percent of the dry matter with no treated stover fed.

The other diets contained treated stover at a rate of 4, 8 or 12 percent diet dry matter, displacing the same proportion of corn grain fed.

The results shown in Table 1 indicate that as the amount of stover increased and the grain decreased, dry matter intakes dropped from 59 pounds per cow per day to 51.7 pounds.

Milk production also decreased linearly from 92.9 pounds per cow per day to 81.4 pounds.

Treating corn stover with lime can significantly improve fiber digestibility, and it has the potential to replace corn grain in growing beef cattle.

For dairy, it may be a viable alternative for lower-producing cows, especially if it replaces corn silage in the diet.

The treated stover does not appear to be as effective in replacing corn grain in high-producing cow diets, but it might be a viable option for heifer diets.

If considering this option, Combs said to think through the treatment process to have a tub grinder or chopper, an adequate water supply and bunkers or bags for storage. Also, remember to take safety precautions when handling quicklime. PD

Photo by PD Staff.

Karen Lee

Editor

Progressive Dairyman