In the most practical terms, what this means for producers is once the hay is cut, the race is on. The faster hay can be cured and put up, the higher the nutritional value.

For many years, prior to the mechanization of haymaking, producers laid hay in wide, unconditioned swaths and made additional passes with conditioners and rakes to gather the hay into harvestable windrows. When haymakers initially began to fully mechanize, harvesting hay crops became faster through greater efficiency. The industry was focused primarily on labor and time savings. The advent of the mower-conditioner simplified the hay-making process, while forming a windrow provided additional harvesting efficiencies. The influence of swath width from haymaking’s early years was overlooked.

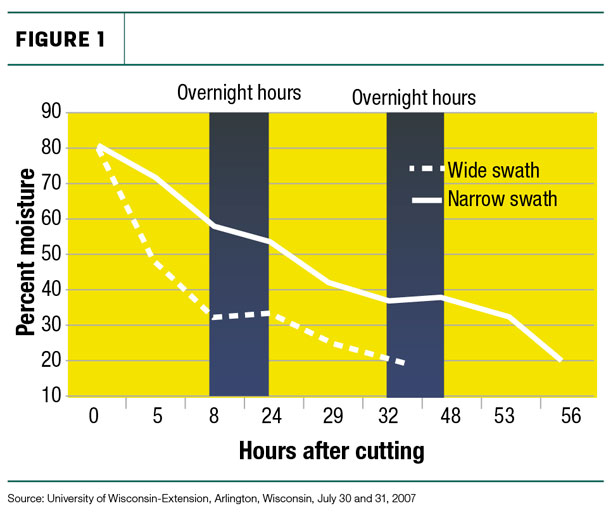

However, the arrival of the “hay in a day” concept brought a resurgence of wide-swathing practices. In response, industry has introduced new mower-conditioner designs with wider conditioning systems. The wide design provides a more direct flow of crop through the conditioner, more uniform conditioning and the ability to form faster-drying wide swaths.

To understand the value of a wide swath, it’s important to review how a hay crop dries. Most often, the drying process is reflected as having three phases: leaves, surface moisture and stems.

The first phase of moisture loss is through open stomata on the leaves. Stomata are little cells that act as doors to allow the exchange of moisture and gasses between plants and the atmosphere. An important thing to remember about stomata is that they are only open when exposed to sunlight. Laying a wide swath exposes more of the stomata to sunlight so they remain open, permitting more rapid initial drying. That’s the first step in achieving faster drying: Lay the crop out wide to “soak up the sun.” A University of Wisconsin – Madison study indicates that rapid drying of this initial 15% of moisture can preserve starches and sugars and result in feed with more total digestible nutrients (TDN). Preserving more value in your crop is the first step in producing higher-quality forage.

The second phase of drying is moisture loss from the plant surfaces. At this point, plant moisture is at or below 60%, and the stomata have closed. Mechanical conditioning during this phase creates artificial openings in the plant to allow moisture to escape easily, and that means faster drying.

The third and most critical drying stage for the production of dry hay is the loss of tightly held moisture. This is moisture trapped in the stems and plant structures. At this stage, mechanical conditioning is essential. Without mechanical conditioning, this moisture would be trapped by the plant structure and drying would slow dramatically. By crimping, cracking and stripping away the cuticle wax layer, tightly held moisture can escape from the stems, continuing the drying process.

In summary, producing quality hay comes down to remembering hay-making fundamentals. The quality of hay and silage crops is determined by what happens immediately after cutting. Swath width and conditioning adjustments are variables that haymakers can control, whereas weather will always be an uncontrolled variable influencing forage quality. Improved quality comes from taking steps to impact these variables in a positive way. Haymakers should evaluate the advantages of both the wide swath and narrow windrows to better understand how each influences the quality of their crop. ![]()

-

Jordan J. Milewski

- Brand Marketing Manager

- Crop Preparation

- New Holland