Selecting the right inoculant is an important one. Most inoculants consist of homofermentative or heterofermentative bacteria or some combination thereof.

Science, new technology and a greater array of solutions have further increased the time it takes to “walk” through the critical control point decision tree. Some critical control points to consider when selecting a corn silage inoculant include:

- Harvest moisture and maturity

- Packing density and porosity

- Fermentation duration

- Conditions at feedout

The critical control points are listed in chronological order, although they are interconnected and affected by each other.

Harvest moisture and maturity

Harvesting at the targeted moisture and maturity plays a significant role in fermentation efficiency and the quality of silage. Corn forage with sufficient sugar and optimal dry matter (DM) content will ensile better than corn that is too dry or too wet.

Corn forage that is too dry will not pack as well, will tend to have less starch digestibility and less aerobic stability at feedout. Corn silage that is too wet will tend to be lower in starch content, have greater opportunity for growth of clostridia and formation of butyric acid, and higher losses from effluent.

Whether the extreme condition is dry with less aerobic stability or wet with increased risk of undesirable fermentation, selecting the right inoculant can mitigate these conditions.

Packing density and porosity

Typically, packing density is expressed as the mass of silage dry matter (DM) per cubic foot. Porosity is the quantity of gas-filled space in a silage pile. Both DM density and porosity are reflective of the exclusion of air from the silage mass; however, porosity is a truer measure of air among the forage particles in the bunker.

Higher density and lower porosity are directly correlated with DM loss during the first phase of fermentation, anaerobic conditions of the silage, efficiency of fermentation and nutrient losses at feedout.

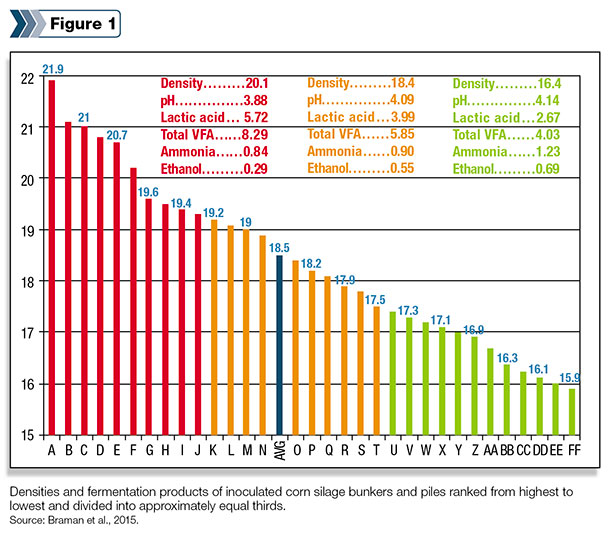

We have measured densities in select inoculated corn silage bunkers and piles ranging from 21.9 to 15.9 pounds DM per cubic foot (Figure 1).

Furthermore, higher densities resulted in lower porosity, pH, ammonia and ethanol, and higher lactic acid and total volatile fatty acids (VFAs) compared with lower densities. Thus, higher-density corn silage bunkers and piles are necessary for optimally effective fermentation, nutrient preservation and the reduction of undesirable end products.

Furthermore, higher densities resulted in lower porosity, pH, ammonia and ethanol, and higher lactic acid and total volatile fatty acids (VFAs) compared with lower densities. Thus, higher-density corn silage bunkers and piles are necessary for optimally effective fermentation, nutrient preservation and the reduction of undesirable end products.

Fermentation duration

Depending on silage inventories, corn silage may ferment for several months or may be fed within days or weeks of harvest; thus, duration of fermentation is a critical control point that impacts inoculant selection.

From 2004 to 2008, Cumberland Valley Analytical Services Inc. used near-infrared analysis of 19,185 corn silage samples submitted from farms in New York to examine how fermentation profiles varied according to the month of the year.

Based on those data, lactic acid and pH did not reach optimum levels until four months after ensiling, whereas acetic acid levels increased until six months after ensiling.

Most measures of fermentation appear to plateau for corn silage approximately four to six months after ensiling, including starch digestibility.

Taken collectively, these and other data indicate the need for at least three months of fermentation before silage can be considered stable. This is especially important when forage inventory is short and early opening is necessary.

Selection of a corn silage inoculant with research-proven rapid production of lactic acid and fast reduction in pH is essential. Furthermore, certain inoculants have demonstrated improved starch availability after relatively short periods of fermentation.

Conditions at feedout

Ultimately, the single-most important goal for making high-quality silage is preservation of the highest quantity and quality of nutrients possible leading up to feedout. Effective management of silage bunkers and piles at feedout can be a significant challenge due to potential losses in excess of 30 percent of total DM loss throughout the ensiling process.

Once silage is exposed to air, yeasts in the silage will begin to utilize remaining sugars and lactic acid in order to flourish. Yeast growth is temperature-sensitive and oxygen-dependent, so lower-density, higher-porosity silage during warmer times of the year experience more significant yeast proliferation.

Some producers manage their silage inventory and base their inoculant selection on the time of year the silage will be fed.

When feeding corn silage during colder winter months, when yeast growth is normally minimal, a homofermentative inoculant would be the recommended choice; however, when feeding corn silage during warmer summer months, when conditions are ideal for yeast growth, a heterofermentative inoculant can reduce the growth of yeast and mold.

Daily silage removal rate is another critical control point when considering corn silage inoculants. At higher density, lower porosity and in colder weather, daily removal rate should be a minimum of 6 inches from the bunker face.

When temperatures warm or the pile has low compaction and higher porosity, daily removal rate should increase significantly in order to reduce oxygen exposure time at the pile face.

Researchers in 1993 evaluated the DM loss of bunker silos as a function of silage removal rate. They determined that DM loss was 3 percent at a removal rate of 6 inches per day for 35 percent DM silage with a density of 14 pounds DM per cubic foot, and DM loss was reduced as silage density increased or porosity decreased.

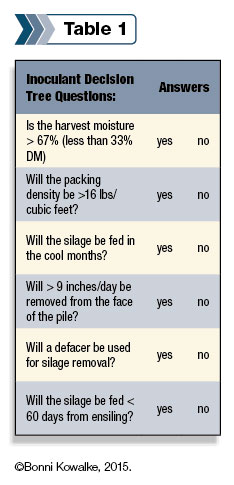

The following critical control point decision tree (Table 1) provides six questions for selecting an inoculant for corn silage.

Three or more “no” answers indicate a need for a heterofermentative inoculant; three or more “yes” answers indicate a need for a homofermentative inoculant.

Homofermentative bacteria species such as Enterococcus faecium generally produce only lactic acid. Heterofermentative bacteria species such as Lactobacillus buchneri will produce lactic and acetic acid; the latter has known anti-fungal properties, thus reducing the detrimental effects of yeasts and molds.

Even with careful consideration of the aforementioned critical control points, sometimes targets are missed or we fall short of our goals. Discussions among key decision-makers and managers now should lead to greater likelihood of a successful corn silage season from harvest through feedout.

Selecting the right inoculant for corn silage is only one of several critical control points that should be considered. FG

Keith A. Bryan is Americas Technical Services Manager, Silage Inoculants and Ruminant DFM, at Chr. Hansen Animal Health and Nutrition

References omitted due to space but are available upon request. Click here to email an editor.

-

Bonni Kowalke

- Regional Account Manager

- Chr. Hansen Animal Health and Nutrition