Here’s a look at hay market conditions in early January.

Supply and demand

The USDA reports capturing supply and demand factors were scheduled after this column’s deadline. Find latest estimates of 2020 production, fall new seeding of alfalfa and year-end on-farm hay inventories elsewhere in this issue and on the Progressive Forage website.

All signs point to the potential of 2021 bringing the highest corn and soybean prices since 2014. With upside risk on the soybean side, there may be more incentive for livestock producers to source protein through forages and other feedstuffs.

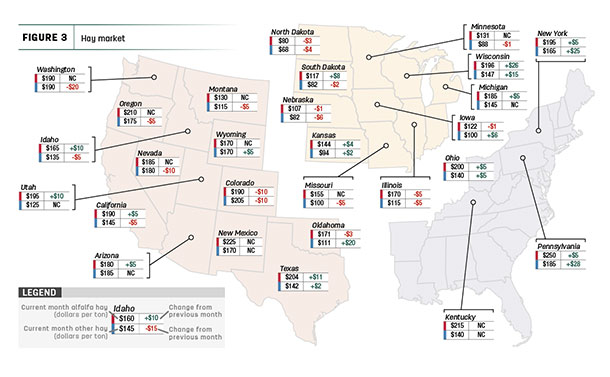

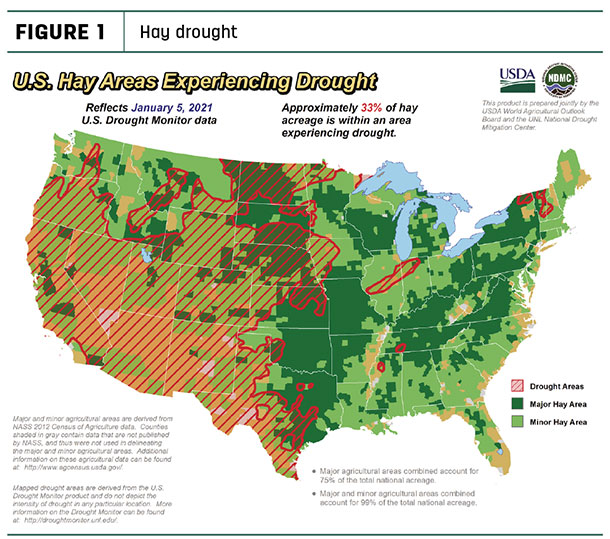

Drought conditions

The end of 2020 brought limited moisture relief to major U.S. hay-producing areas. As of Jan. 5, about 33% of U.S. hay-producing acreage (Figure 1) was considered under drought conditions, a 7% decline from early December. However, half of all U.S. alfalfa-producing acreage remained under drought conditions, unchanged from a month earlier (Figure 2) and the most since the fourth quarter of 2012.

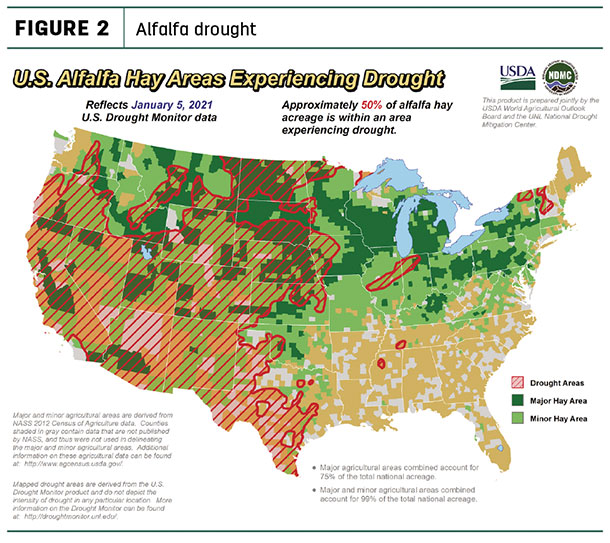

Hay prices mapped

Despite a jump in the average price for high-quality dairy hay, the national average price for all alfalfa hay declined $4 in November 2020. At $167 per ton, it’s a 33-month low. The U.S. average for other hay rose $4 from October to $136 per ton.

The data for 27 major hay-producing states is mapped in Figure 3, illustrating the most recent monthly average price and one-month change. The lag in USDA price reports and price averaging across several quality grades of hay may not always capture current markets, so check individual market reports elsewhere in Progressive Forage.

Click here or on the map above to view it at full size in a new window.

Alfalfa

Among the 27 states, November average alfalfa hay prices increased in 12 states, led by a $26 jump in Wisconsin and increases of $10 or more in Texas, Idaho and Utah. November prices declined in six states, led by a $10 drop in Colorado. Prices averaged more than $200 per ton in Pennsylvania, New Mexico, Kentucky, Oregon and Texas and Ohio, but just $80 per ton in North Dakota.

Other hay

November prices for other hay moved higher in nine states, led by increases of $15-$28 per ton in Pennsylvania, New York, Oklahoma and Wisconsin. Declines were reported in 13 states, led by Washington, Colorado and Nevada. Colorado had the top monthly average of $205 per ton; prices were $94 or lower in Kansas, Minnesota, Nebraska, South Dakota and North Dakota.

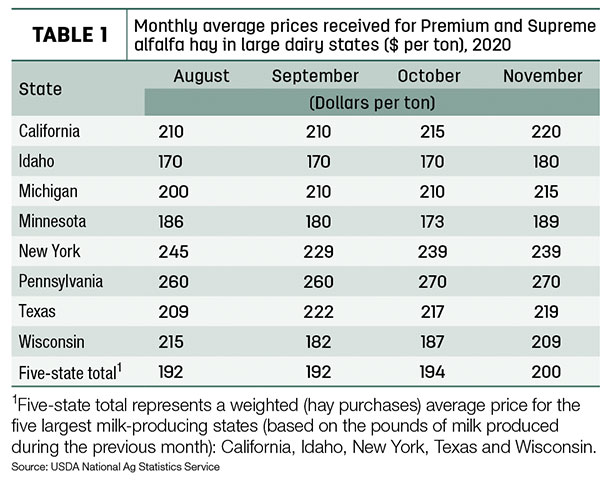

Dairy hay

The average price for Premium and Supreme alfalfa hay in the top milk-producing states averaged $200 per ton in November, up $6 from October (Table 1) and the highest since June. Prices were steady in New York and Pennsylvania but higher in other dairy states.

Organic hay

The USDA’s organic hay price report summarized f.o.b. farm gate prices as of mid-December. High-testing large square bales of Supreme alfalfa topped the market at $275 per ton, while other Fair-Good alfalfa averaged $212 per ton.

Exports: Survival mode

November 2020 hay exports were below year-earlier levels, continuing a trend started last summer. At 189,165 metric tons (MT), alfalfa hay exports fell about 20,000 MT from October, with sales to China the lowest since January-February 2020. Small monthly increases to Japan and South Korea offset declines to Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates and Taiwan.

Exports of other hay rose to 120,245 MT, a six-month high. Sales to Japan and South Korea were up slightly in November, with shipments to other major markets mostly steady.

Those numbers may not adequately illustrate an industry locked in survival mode, said Christy Mastin, sales representative with Eckenberg Farms, Mattawa, Washington.

Shipping remains the biggest issue, and the challenges have increased since October, Mastin said. While there are fewer “blank” sailings or the skipping of ports, long delays due to shortages of vessel space, access to terminals, equipment and labor are being experienced across all West Coast ports. A delay in one area creates delays in the next. One recent request for open cargo space, which in the past would have taken seven days to fulfill, instead took seven weeks.

Shipping lines have always realized a higher return for carrying import cargo into the U.S. than exporting cargo from the U.S. With the income differentials and loading delays, shipping lines are giving space to empty containers returning to Asia to be filled and imported back to U.S. at more profitable returns.

Oversold space on outgoing vessels creates a domino effect as scheduled cargo is rolled back to the next available vessel. Hay customers place orders from multiple suppliers in the hope that someone can get a shipment to them in a timely manner and then adjust other orders once the shipments are made.

The delays create stress on livestock feeders in search of feed to keep animals alive and productive and may result in uneven inventories, stretching storage capacities and impacting new purchases.

Traditionally, shipments to China decline at year’s end to avoid arrival during the Chinese New Year, and Mastin expects sales to China to pick up after that – if cargo space can be found. China’s milk prices have increased as the country has promoted milk as a means to boost immunity to COVID-19.

Looking ahead, the U.S. dollar is weakening against major hay-trading partners, improving the export outlook. However, frustration over shipping is high and expected to continue through March, Mastin said.

Regional markets

Here are more local snapshots of conditions and markets:

- Southwest: In Texas, hay prices were firm in the Panhandle and west and steady elsewhere thanks to some much-needed rain.

In California, demand for retail and dairy hay was moderate.

In Oklahoma, hay trade remained slow, hampered by wet fields that made loading difficult. Demand for ground alfalfa remained moderate to good as most feedyards seemed to be current on needs.

- Northwest: The quarterly update from Northwest Farm Credit Services (FCS) forecast a modestly optimistic profitability outlook for hay producers.

In Wyoming, all hay sold steady, with most contracts sold out. Buyers are looking for hay for winter feeding. The snowpack is lighter than normal.

In Montana, hay sold steady to $10 higher. A mild winter to date had curbed supplemental feeding needs. Round hay supplies were tight, and buyers were purchasing rounds at the same price as squares. Hay continued to ship to Wyoming in large quantities.

In Idaho, all grades of hay sold firm as winter set in; trade remains slow. Premium alfalfa was trading slightly under $1 per point of relative feed value (RFV).

In Colorado, trade activity was light on moderate to good demand for stable, feedlot and dairy hay; activity was lightest in the northeast.

In the Washington-Oregon Columbia Basin, export-quality alfalfa sold firm, and exporters were willing to accept lower grades of hay. Retail-feedstore hay sold steady; Utility-Fair timothy and alfalfa sold weaker. Mild winter weather has eased hay demand from beef and dairy producers.

Demand in the Oregon-California Klamath Basin was on the rise, with dry weather driving beef producers to buy more Fair-quality hay. In some instances, beef producers are outbidding dairy producers for hay supplies.

- East: In Pennsylvania, demand for alfalfa and alfalfa-grass blend hay was moderate and lighter for grass hay. Large bales of straw sold on moderate demand; demand for small bales was lighter.

In Alabama, prices were fully steady on good demand and moderate supply.

- Midwest: In Missouri, mild temperatures meant producers were feeding in the mud. Hay supply, demand and movement were moderate; prices were mostly steady. Previously sold hay was being delivered, with much of it staying local. Equine demand for high-quality hay was very good.

In Nebraska, hay prices were mostly steady with hay moving out of state. Light snow bumped up supplemental feeding a bit.

In Kansas, hay prices were steady to slightly higher for alfalfa hay and steady for grass hay. In the southwest, alfalfa was harder to find, although there were expectations inventories would loosen as winter progresses.

In Iowa, alfalfa sold mostly steady; grass hay was steady with variations in quality. Straw was weaker and cornstalks sold steady.

In South Dakota, alfalfa hay sold fully steady. Abnormally mild weather lessened the need for supplemental feeding. The best demand came from out-of-state dairies seeking high-testing alfalfa in large square bales. With plenty of winter remaining, hay producers are not feeling pressure to sell.

In Wisconsin, there was strong demand for dairy-quality large square bales and less demand for lower-quality round bales.

Other things we’re seeing

-

Dairy – The U.S. dairy herd continues to grow and is now the largest since June 2018. Milk production is increasing at a rate many consider too steep to sustain prices in 2021.

-

Quality loss payments – The USDA unveiled a Quality Loss Adjustment (QLA) program, providing financial assistance to producers who suffered eligible crop quality losses due to natural disasters occurring in 2018 and 2019. Eligible forage crops must have had at least a 5% nutrient loss, such as total digestible nutrients. Deadline to apply is March 5, and producers must provide verifiable documentation to support claims of quality or forage nutrient loss. Contact your local USDA FSA office for details.

-

Crop inputs – The outlook for fertilizer prices and supply are mixed, according to a quarterly outlook from Northwest FCS. Higher crop prices favor increased fertilizer demand. On a positive note, fertilizer companies and co-ops took advantage of low fertilizer prices last summer to build inventories, and stronger cash flows helped producers either purchase and apply fertilizer last fall or prepay for 2021 spring fertilizer.

-

Dave Natzke

- Editor

- Progressive Forage

- Email Dave Natzke