On its present path, signs point to Texas becoming the third-largest milk-producing state in the U.S. by 2025. Based on USDA estimates from January 2022, Texas cow numbers have more than doubled in about two decades. The milking herd in the High Plains region alone numbers more than 475,000 cows, pushing the state’s total to about 625,000 head.

Milk production growth in Texas has also been staggering, up 190% from 2001-20. Production grew about 5% in 2021, edging out New York as the fourth-largest dairy state and leaving it about 25,000 cows and 850 million pounds of milk (annually) behind No. 3 Idaho.

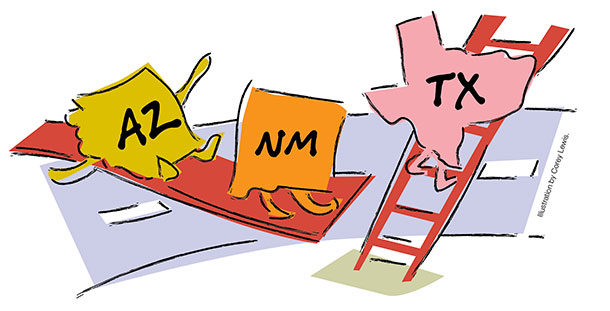

Traveling west on Interstate 40, however, the signs begin to change. New Mexico’s cow numbers to start 2022 were down 45,000 head from a year earlier, and milk production during the second half of 2021 was down nearly 11% compared to the same period in 2020. Arizona’s January 2022 cow numbers were down 4,000 head, with July-December milk production down more than 2% from the same period in 2020.

Michael Reecy, vice president of dairy-related business for Farm Credit Services of America, said contraction in New Mexico, Arizona and stretching into California is being driven by factors dairy managers have less control over, including access to water, which also leads to higher input costs.

“Those cows are leaving, and I don’t think they’re going to come back in that area,” Reecy said.

A look at Texas

Thanks to stronger prices, exports and increasing processing capacity, as well as pandemic-related government assistance, Texas dairy producers have plenty to be optimistic about entering 2022, said Jennifer Spencer, Texas A&M AgriLife Extension Service dairy specialist located in Stephenville.

At the same time, last year wasn’t without stress, leaving many producers weary and looking for a better year ahead, according to Darren Turley, executive director of the Texas Association of Dairymen (TAD).

“Texas producers have had a long, stressful year full of tough economic decisions on their farms,” Turley said. “Last year started with a record ice event that engulfed the entire state, then low milk prices carried throughout the year.”

Up until recent years, growth in Texas milk processing capacity and milk production potential have been a convoy on the same road. Plant construction and expansion was matched by increasing cow numbers and milk production growth. More recently, the pace of milk production growth has surpassed the ability to process and market it, leading to the implementation of production controls and a tiered pricing system in 2021 that continues into 2022. That program will soon be up for renewal, however, and announcements of new processing plants in the Texas Panhandle have prompted some producers to question continuation.

“Texas production control programs have turned out to be a successful buyout program for producers interested in leaving the business,” Turley said. “This program has gone on long enough that a significant number of producers are ready to close the program.”

Processing capacity is expanding, especially in the Texas Panhandle, notes Juan Piñeiro, Texas A&M AgriLife Extension Service dairy specialist located in Amarillo. Cacique LLC, a privately owned maker of Mexican-style cheese, is scheduled to begin operation of a processing facility in Amarillo this fall. Another plant, in Dumas, is also under construction. This summer, a new Leprino mozzarella cheese and dairy ingredients plant is scheduled to break ground in Lubbock, with completion in two phases by early 2026.

Additionally, the Hilmar Cheese Company is building a cheese and whey protein processing plant in Dodge City, Kansas, which will draw milk from southwest Kansas and away from processors further south in Texas. That plant is expected to be fully operational in 2024.

“These new plants are expected to fill quickly, so the milk surplus could return as well,” Turley said. “Texas is poised for growth, but we have had to move more milk than our markets can handle, and we do not need to return to that position.”

According to Piñeiro, it’s difficult to make a blanket statement about the financial health of all 335 commercial dairy farms in Texas. In general, larger herds in the Texas Panhandle are in better shape financially than the smaller dairy farmers in east and north-central Texas.

Texas had a strong hay and forage production year in 2021, contributing to the largest on-farm inventories of hay supplies to end the year than any other state. Dairy-quality hay prices have been fairly stable since May 2021, although they ended 2021 about $25 per ton higher than a year earlier.

Like elsewhere, labor access and affordability, water scarcity and escalating input costs are big concerns entering 2022, said Piñeiro.

Labor shortages are not only in number but also in qualifications, Spencer added. “The incorporation of technology onto dairies is creating a demand for employees who are well versed in technology and willing to expand their knowledge in the future,” she said.

Markets look promising

Fueled by population growth, Texas has a strengthening domestic dairy market. As of the 2020 Census, Texas had more than 29 million residents, and the 2021 Texas Relocation Report estimated more than 500,000 people moved to Texas in seven consecutive years as of 2019 (the latest date available). Given its proximity, Texas producers are also poised to deliver milk and dairy products into Mexico, the leading U.S. dairy export market, Turley said.

The population growth is also increasing the need to address environmental concerns. Several dairy operations are working to add digesters, capturing methane from dairy manure lagoons and converting it to natural gas and reducing greenhouse gas emissions, Turley said. The organization is monitoring environmental legislative activity critical to the dairy industry, as well as ways to improve electrical grid reliability and the wholesale electricity market.

Product diversification and processing capacity growth have helped buffer many Texas producers against the negative impacts created by changes to the “Class I mover” pricing formula. While arguments for Federal Milk Marketing Order (FMMO) reform grow louder, the state’s producers want an intensive review before further changes are made, Turley said.

“The Texas dairy industry is very strong. The dairy producers in Texas are forward-thinkers and are driven to make changes to help create a sustainable future for the dairy industry,” concluded Spencer.

New Mexico: Optimism, pessimism

In terms of the average number of cows, New Mexico leads the nation with at or near 2,500 cows per herd. While economies of scale provide some financial benefits, they have their limits.

“Federal programs are and continue to be capped, putting the large producers in the West at a disadvantage with producers elsewhere in the country,” said Robert Hagevoort, associate professor and Extension dairy specialist with New Mexico State University – Clovis. “In addition, in areas a long distance from markets, with generally lower milk prices such as New Mexico, this becomes a double whammy.”

Additional processing capacity is keeping up with milk production growth in the region but not adding to New Mexico producer pay prices, which are generally the lowest in the country and frequently $2 per hundredweight (cwt) less than the U.S. average “all-milk” price, Hagevoort said.

For that reason, the outlook for milk prices in New Mexico offers both optimism and pessimism, Hagevoort said. Recently released financial reports by leading account firms continue to show significant financial losses for New Mexico dairy producers in the first six months of 2021.

“As a result, we are seeing very significant and accelerated consolidation, with larger-than-normal numbers of dairies calling it quits,” Hagevoort said.

FMMO market administrator reports show New Mexico lost 15% of its dairies in 2021 (down 19 from 128), and total production decreased 5%.

The disparity in milk prices has New Mexico producers looking at the pricing structure and reforms.

“Producers in New Mexico need a pricing structure that places them in greater parity to their neighboring producers. This is important both for our individual farmers and for the health of New Mexico’s overall dairy industry,” Hagevoort said.

The state’s producers see many of the same challenges related to input costs and labor as producers throughout the U.S.

Despite a summer well suited for forage production, fall drought and anticipation of a La Nina winter, area nutritionists said December feed costs were up 20% to 25% compared to the same time a year ago.

“In essence, there are two solutions for not being able to grow enough feed: You buy the feed elsewhere and bring it to the cows, or you take the cows to where the feed is. Both come at a cost, and milk prices have not been of any help,” Hagevoort said.

Dairy has been in longstanding competition for labor with the oil and gas industry in the Permian Basin. The water situation in the Southwest continues to be a challenge, and producers are looking at other options besides doing everything they can to be as efficient as possible.

“The most successful producers I work with pay considerable attention to the totality of their operations and are aware of the continuing evolution of dairy farming,” Hagevoort said. “Those [who] limit their primary focus to simply producing milk are those most at risk of falling victim to the continued consolidation of the industry.”

“The state of the industry requires that producers be engaged in proactively working to hedge both milk sales and inputs, educate themselves about both the demands and opportunities related to sustainable and environmental improvement, develop and maximize the potential of their human capital, and be more actively involved in their producer groups. The real benefit of being engaged and active in these areas is that it will pay tangible dividends – incremental, certainly, and perhaps not immediately – but there is an economic benefit to running a progressive dairy,” Hagevoort concluded. ![]()

ILLUSTRATION: Illustration by Corey Lewis.

Also read:

2022 State of Dairy: A melding of moods and concerns

Northeast: A brighter price outlook, but uncertainty abounds

Southeast: The struggles continue

Mideast: Balancing multiple market forces

Wisconsin the Midwest base for ‘forward’

Appalachian market shares Southeast challenges

I-29 Corridor: At the intersection of growth and balance

Water, regulations add to regional challenges